November 16, 2017 Reading Time: 5 minutes

Reading Time: 5 min read

Reading Time: 5 min readImage Credit – Iam_Autumnshine / depositphotos

Barana Waidyatilake*

The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) is a potentially key multilateral forum for Sri Lanka in its ambitions to become a regional hub in the Indian Ocean between Singapore and Dubai. Formed in 1997, the 21-member IORA is the only forum that specifically connects the states of the Indian Ocean region, which is fast becoming one of the major geopolitical theatres of current global politics.

IORA made little progress in its first 20 years towards its founding goal of enhancing regional economic cooperation1 due to a lack of interest from major powers, including India and Australia. However, 2017 has been a landmark year for IORA. The first IORA Leaders’ Summit was held in March of this year with Sri Lankan President, Maithripala Sirisena, in attendance. The meeting ended with the signing of the Jakarta Concord, which sets important standards related to freedom of navigation, counterterrorism, and enhancing regional trade that could form the basis of a rules-based framework for the Indian Ocean. The Concord was accompanied by an Action Plan, an initiative that sets concrete targets for the organization in the short, medium, and long terms.

The IORA Leaders’ Summit was followed by a Council of Ministers’ meeting in Durban, South Africa on October 18, attended by Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Tilak Marapana. At this meeting, Marapana lobbied for a stronger role for Sri Lanka within IORA. As a result, Sri Lanka was chosen as the lead coordinator2 for IORA’s Working Group on Maritime Safety and Security. Sri Lanka’s desire to lead within IORA is underpinned by the country’s growing self-awareness of its strategic location in the Indian Ocean as well as its vulnerability in the context of regional great power competition.

These developments indicate that this is an opportune time for Sri Lanka in the IORA. This article suggests how Sri Lanka can step up its engagement within IORA to realize its own national and security interests through this critical, multilateral forum.

Small states like Sri Lanka especially stand to gain from a rules-based order in the Indian Ocean. Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, originally raised the idea3 of a Code of Conduct for the Indian Ocean even before the Jakarta Concord. Now that the Jakarta Concord has laid a foundation for a rules-based order in the region, Sri Lanka should lobby proactively with other small states in IORA – such as Singapore, Mauritius, and the Seychelles – to strengthen the Concord into a formal Code of Conduct to address common issues in the region.

Moreover, Sri Lanka should lobby for an effective, legally-binding dispute resolution mechanism to be incorporated into any potential Code of Conduct. There is currently no such mechanism attached to the ASEAN Code of Conduct for the South China Sea,4 for example, which has led to criticisms of the code’s effectiveness. The increasing importance of the “blue economy” and Sri Lanka’s own disputes with neighbouring states like Bangladesh over the delimitation of its Exclusive Economic Zone also provides Sri Lanka with an impetus for introducing such a mechanism.

Sri Lanka should also take steps to strengthen its regional role in combatting non-traditional security threats. Wickremesinghe has suggested that the Sri Lankan Navy should patrol “the sea off Banda Aceh and the Straits of Malacca.”5 Such a step would, in the long run, help Sri Lanka plug a gap in Indian Ocean security coverage through anti-piracy patrols such as Combined Task Force 151 and Operation Atalanta6 in the western Indian Ocean and “minilateral” security mechanisms such as the Malacca Strait Patrol7 in the eastern Indian Ocean.

As mentioned above, Sri Lanka has already taken an important step in demonstrating leadership in maritime security through its role as lead coordinator for IORA’s Working Group on Maritime Safety and Security. One of its first steps in performing this role should be to realize a key maritime security goal in the IORA Action Plan: strengthening the Working Group’s cooperation with United Nations (UN) offices and agencies.

Sri Lanka could reach out to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), given that UNODC’s Indian Ocean Forum on Maritime Crime is already based in Sri Lanka.8 In particular, Sri Lanka could promote UNODC’s piracy prosecution model9 – which seeks to increase the efficiency of legal action against piracy in the western Indian Ocean – as a model for the whole Indian Ocean region. By doing so, Sri Lanka would also underscore the importance of robust normative responses in maintaining regional security.

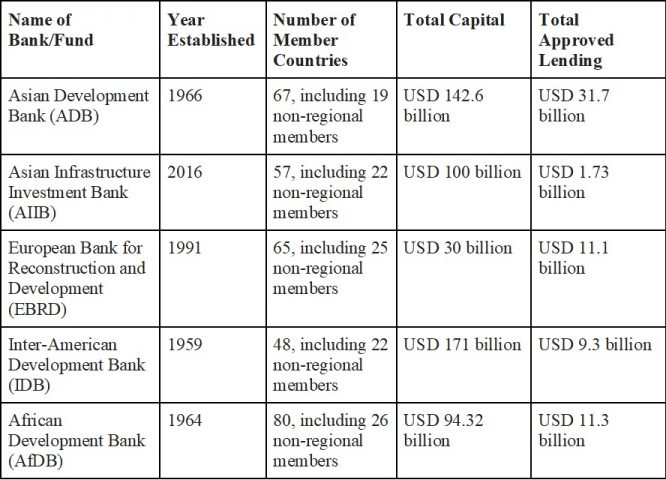

Finally, Sri Lanka should develop a strategy to realize Wickremesinghe’s proposal to establish an Indian Ocean Development Fund under IORA, similar to other regional development banks to allow for further investment in affiliated nations (see Table 1). Such an initiative could help finance infrastructure development, climate change adaptation efforts, and small and medium enterprise (SME) development. While Australia and Singapore are the only developed nations in IORA, there are nevertheless several important economies in the region such as India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, that could potentially contribute towards such a fund. Sri Lanka should advocate this idea outside of IORA in its bilateral diplomacy with these nations.

Table 1: The World’s Major Regional Development Banks*

*As of 31 December 2016

Sources: ADB – Who We Are; AIIB Quick Facts; IADB Key Facts; EBRD Annual Report 2016; The African Development Bank Group – Fast Facts

Sri Lanka should also consider proposing an extraordinary meeting of the Council of Ministers to discuss establishing such a fund with all IORA member states. Additionally, Sri Lanka should seek to tie the fund to current IORA focus areas in economic cooperation, such as the promotion of SMEs, on which a January 2017 memorandum of understanding10 has already been signed among IORA member states.

IORA began 2017 with a relative bang. It remains to be seen whether this momentum can be sustained. The current shifts in the global balance of power and resulting uncertainties could elevate IORA to play a more significant role in the region and beyond. Sri Lanka, as a strategically-located IORA member state with the ambition of becoming a hub of the Indian Ocean, has a clear interest in promoting a stronger, rules-based IORA from which it should not shy away.

1Jivanta Schöttli, The Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Co-operation: India Takes the Lead, Future Directions International, 1 June 2012, accessed on 3 November 2017, http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/the-indian-ocean-rim-association-for-regional-co-operation-india-takes-the-lead

2DailyFT, ‘Foreign Minister Marapana Attends IORA Council of Ministers Meeting’, DailyFT, 24 October 2017, accessed on 31 October 2017, http://www.ft.lk/news/Foreign-Minister-Marapana-attends-IORA-Council-of-Ministers–Meeting/56-642099

3Ranil Wickremesinghe, Freedom of Navigation in the Indian Ocean, 2017 Deakin University Law School Oration, delivered on 16 February 2017.

4Ian Storey, ‘Assessing the ASEAN-China Framework for the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea’, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute Perspective, No.62, 8 August 2017, accessed on 31 October 2017, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_62.pdf

5N. Sathiya Moorthy, ‘Blue-Water Navy, Without a Name!’, Sunday Leader, 17 April 2016, accessed on 31 October 2017, http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2016/04/17/blue-water-navy-without-a-name

6EU Naval Force Somalia, Mission, European Union External Action, accessed on 31 October 2017, http://eunavfor.eu/mission

7Ministry of Defence, Republic of Singapore, Fact Sheet: The Malacca Strait Patrol, 21 April 2016, accessed on 31 October 2017, https://www.mindef.gov.sg/imindef/press_room/official_releases/nr/2016/apr/21apr16_nr/21apr15_fs.html

8United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Maritime Crime Programme: Indian Ocean, accessed on 31 October 2017, http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/Indian-Ocean.html

9United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Maritime Crime Programme: Indian Ocean, accessed on 31 October 2017, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/indian-ocean-division.html

10Economic Times, ‘India Finalises MoU on MSME Cooperation with IORA Nations’, Economic Times, 21 January 2017, accessed on 31 October 2017, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/policy-trends/india-finalises-mou-on-msme-cooperation-with-iora-nations/articleshow/56687790.cms

*Barana Waidyatilake is a Research Fellow at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). All errors and omissions remain the author’s. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own views. They are not the institutional views of the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute, and do not necessarily represent or reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which he is affiliated. A version of this article originally appeared at South Asian Voices, an online platform for strategic analysis and debate hosted by the Stimson Center.