Understanding the World Trade Organization

March 7, 2018 Reading Time: 10 minutes

Reading Time: 10 min read

Image Credit – World Trade Organization / flickr

This LKI Explainer examines the significance of the World Trade Organization from a Sri Lankan perspective. It provides an overview of the WTO’s mandate and core functions and its links with Sri Lanka. Additionally, it analyses the system’s current challenges and explores possible reforms to the system.

Contents

1. What is the World Trade Organization?

2. The WTO’s Core Functions

3. Sri Lanka and the WTO

4. The WTO Under Threat

5. MC11 and the Future Outlook

1. What is the World Trade Organization?

- The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the only international organisation that regulates the global rules of trade between nations. Its main mission is to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible.1

- The WTO commenced on 1 January 1995, and was established under the Marrakesh Agreement of 1994.2 It replaced its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which had commenced in 1948.

- The WTO membership is quasi-universal. There are currently 164 member states in the WTO. This means that over four-fifths of all countries are WTO member states.

- The WTO has, at its core, the principle of non-discrimination, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of ‘national origin or destination’ of a product. This, in turn, reduces protectionism between individual states and creates a ‘level playing field’ in international trade. The principle of non-discrimination is divided into two sub-principles:

- National Treatment: Imported goods should be treated no less favourably than domestically produced goods.

- Most-Favoured-Nation treatment (MFN): If a WTO member grants favourable treatment (for example, lower custom duty for a product), it must do the same for all other WTO members.

- Other key principles include free trade, fair competition, predictability and transparency, which are reiterated in the WTO’s constituent document.

- By acceding to the WTO framework, each member state has the obligation to adhere to the organisation’s main principles as well as WTO trade agreements and rules:

“Each Member shall ensure the conformity of its laws, regulations and administrative procedures with its obligations as provided in the annexed Agreements.”3

2. The WTO’s Core Functions

- The WTO has the following core functions:

- Trade Negotiations

- Dispute Settlement

- Monitoring

- Information and Capacity-Building

Trade Negotiations

- The WTO is a forum for negotiations between states. Through negotiating trade agreements between members, barriers to trade are reduced on a multilateral basis. Therefore, in order to fulfil the WTO’s main mission of ensuring that trade flows as freely and fairly as possible, the process of negotiation is essential.

- The biggest forum for trade negotiations is a WTO Ministerial Conference, which takes place every two years and brings together all member states. During such conferences, specific issues related to global trade are discussed, and decisions can be made on matters that fall under multilateral trade agreements.

Dispute Settlement

- The WTO’s dispute settlement system is a multilateral system for settling disputes between members that have violated trade rules. If any member acts contrary to the WTO Agreements,4 a complaint can be lodged by another member state before the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB).

- Through this system, the rights, obligations and agreements between member states are preserved, and the existing provisions of those agreements are clarified.5 Without a means to settle disputes, the rules-based system would be less effective, as the rules could not be enforced.

Monitoring

- The WTO’s monitoring function includes oversight, implementation, administration, and operation of the covered agreements. In particular, the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM) allows for periodic reviews of the regulations of a WTO member state to check whether they are in accordance with WTO law.

- The TPRM helps contribute to the smooth functioning of the multilateral trading system by enhancing the transparency of members’ trade policies.

Information and Capacity-Building

- Information and capacity-building consists of conducting economic research and collecting and disseminating trade information to deepen understanding about trends in trade, trade policy issues and the multilateral trading system.

- Capacity-building includes assistance awarded to developing countries, particularly least developed countries, to participate more fully in the global trading system.

- Such assistance mainly consists of helping officials to better understand complex WTO rules, so that they can properly implement WTO agreements. This allows them to negotiate more effectively with their trading partners and to improve their trading regimes.

3. Sri Lanka and the WTO

- Sri Lanka became a member of the GATT in July 1948, soon after its independence.

- Sri Lanka became a member of the WTO at its establishment on 1 January 1995.

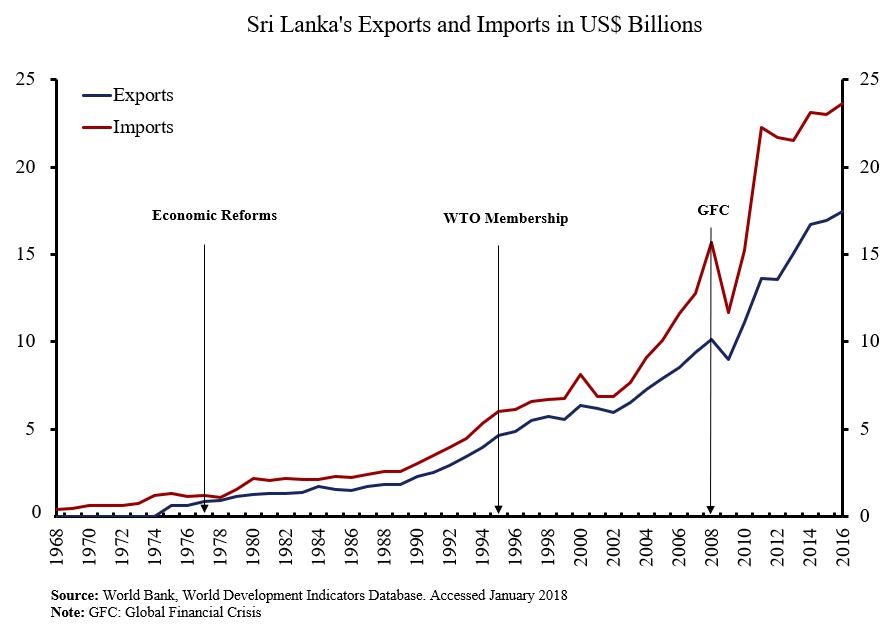

- After the 1977 economic reforms in Sri Lanka, the country was able to better adhere to the obligations set by the WTO. As with other member countries, Sri Lanka thereafter strived to trade globally while promoting fair competition, national development, and economic reform.

- Figure 1 indicates that Sri Lanka’s trade has steadily grown over the years.

Figure 1:

- Sri Lanka was part of the following key WTO rounds of trade negotiations:

- The Uruguay Round, which began in 1986, lasted until 1994 and led to the establishment of the WTO; and

- The Doha Round, which began in 2001 and in which Sri Lanka had an active role in discussing issues such as agriculture, services, trade facilitation, Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), and ‘aid for trade’ in accordance with its trade and economic interests.

- Sri Lanka is currently active in the WTO negotiations in the areas related to its trade and economic interests, specifically: Non-Agricultural Market Access, agriculture, trade facilitation, services, TRIPS, and Aid for Trade.

Sri Lanka’s Use of the Dispute Settlement Mechanism

- Sri Lanka’s involvement and use of the WTO’s dispute settlement system has been limited to four uses; once as a complainant and thrice as a third party.

- The dispute settlement case between Sri Lanka and Brazil in 1996, in which Sri Lanka was the complainant, is an example of a violation of one of the WTO’s core principles; specifically, of MFN treatment.

- The issue at stake was the justifiability of countervailing duties imposed by Brazil on the import of desiccated coconut and coconut milk powder from Sri Lanka, due to the domestic support the Sri Lankan government gave to its local farmers.

- The DSB ruled that the countervailing duties were not justified under the WTO Agreement on Agriculture, in which domestic support measures were given to Sri Lanka’s coconut industry.

Recent Developments

- As mentioned earlier, the TPRM is the WTO’s review mechanism which periodically examines the regulations of WTO member states and their contribution to the WTO. Sri Lanka has been under such review four times, the most recent being in 2016.

- Sri Lanka signed the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) on 31 May 2016. As noted by commentators:

“Implementation of this Agreement will bring positive results to developing countries, and Sri Lanka can consequently improve its competitiveness in the global market and attract FDI through the application of simplified border control measures in supporting trade.”6

Benefits for Sri Lanka

- The WTO follows a theory of international trade based on pure free market forces. This translates to advocating for lower or no subsidies and tariffs.

- Being part of the WTO grants Sri Lanka equal access to other markets, which directly enhances trade.

- The dispute settlement system enables smaller states like Sri Lanka to resolve disputes with much larger countries through a rules-based system. This helps prevents unfair treatment by major trading powers, against which Sri Lanka would otherwise have limited leverage to retaliate.

- Most developing countries tend to focus on agricultural products, allowing them to specialise in a few and create a comparative advantage. Sri Lanka was able to do the same. Sri Lanka took the opportunity to use the WTO as a platform to maximise the benefits of specialisation.

- Among the many issues discussed at the WTO’s 2017 Ministerial Conference (MC11) in Buenos Aires, significant progress was made on fisheries subsidies, which could be beneficial to Sri Lanka if an eventual agreement is signed.

- Though the fishing industry is not a major contributor to GDP, it accounts for 10% of Sri Lanka’s workforce.

- Sri Lanka would be able to benefit from tighter control on illegal fishing and lower subsidies. Local fisherman will be able to benefit from an equal playing field.

4. The WTO Under Threat

The Dispute Settlement Mechanism

- Although many agree that the dispute settlement mechanism is working reasonably well, only a few Asian countries (Japan, China, South Korea and India) use the system regularly.

- The dispute settlement mechanism has also been recently criticised by the US government. The Trump Administration has criticised it and asserted the right to ignore rulings that it believes would violate the sovereignty of the US.

“Even if a WTO dispute settlement panel rules against the US, such a ruling does not automatically lead to a change in US law or practice. The Trump administration will aggressively defend American sovereignty over matters of trade policy.”7

- Key gaps in the system include:

- Resource constraints and costs of dispute settlement;

- Legal ‘standing’ to complain – only governments (not exporters) can bring disputes to the WTO;

- DSB panelists work part-time, which may reduce the quality and consistency of their reports; and

- Lack of compensation for damages incurred.

- The system would be strengthened by addressing these gaps of the DSB mechanism.

Stalling of the Doha Round

- The Doha Round was launched in November 2001 at the WTO’s 4th Ministerial Conference in Qatar. Its main objectives were to:

- Achieve major reform of the international trading system through lower trade barriers and revised trade rules; and

- Boost trade and growth of developing countries.

- Negotiations stalled in 2008 due to differences in opinion between developed nations (EU countries, US, Canada) and major developing countries (India, China, Brazil) on agriculture, industrial tariffs, non-tariff barriers, services and trade remedies.

- Outcomes of the Doha Round were limited, especially on core 20th century trade issues. The future of the round remains uncertain.

5. MC11 and Future Outlook

Departing from the Doha Round, WTO member states saw opportunity at MC11 held in Buenos Aires in December 2017, which addressed key issues including fisheries, agriculture, and e-commerce.8 The discussions covered the following issues:

- Fisheries

- The notion to eliminate fishery subsidies has been widely discussed and it is also covered by some of the Sustainable Development Goals. However, there is no clear consensus on which subsidies should be allowed or eliminated.

- Agriculture

- Subsidies and public stockholding programmes have been some of the main issues discussed over the years.

- Subsidies for example, can create an inefficient allocation of resources as they artificially depress prices. They make it difficult for farmers who do not receive subsidies to compete.

- Public stockholding is the practice of buying food stocks through administered prices—it is a trade distorting practice and therefore, requires regulation.

- A “peace clause”9 that shields some breaches of WTO limits was an interim solution adopted at the Bali Conference to address this issue. Proper regulation was meant to be put in place at MC11.

- E-commerce

- Members are currently not imposing any custom duties10 on electronic transmissions and are urged to continue this practice.

- One challenge is how to facilitate trade and reduce tariffs on goods traded under e-commerce. Discussions are necessary to address the required rules with regard to the growing digital economy.

Outcomes from MC11

- Fisheries

- One of the outcomes of MC11 was the agreement to continue to engage in talks on fishery subsidies.

- This was done with the aim of adopting a comprehensive set of disciplines to reduce overcapacity and overfishing, and to eliminate subsidies that contribute to Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing by 2019.

- Agriculture

- There was no significant progress on agricultural issues, due to a lack of consensus in this area.

- This meant that interim regulations on public stockholding decided at the Bali Conference are likely to continue for the time being.

- Several participating Ministers were rather disappointed as talks on this matter were mandated to conclude at MC11. Other areas of discussion, including a Special Safeguard Mechanism and domestic regulation, faced similar obstacles.

- E-commerce

- Periodic reviews have been scheduled for July and December 2018, and July 2019, to ensure work is progressing towards a comprehensive draft of regulations.

- Members also pledged to maintain the current practice of not imposing custom duties on electronic transmissions until the next session in 2019.

Future Outlook for the WTO

- MC11 concluded on a disappointing note, as progress was stalled due to various factors.

- In his concluding remarks, Director-General Azevedo stated that although 164 countries engaged in talks and worked closely together, significant progress in some areas did not seem possible.11

- Ministers were unable to find a common position to support measures and regulation in some areas. Hence, most were disappointed at the pace of the talks.

- The Director-General reiterated that, “mindsets will need to change if we are to advance.”12

- In recent months, a protectionist sentiment seems to be gaining popularity.

- The Trump Administration’s attack on the WTO indicates that the US is starting to pull away from the WTO, towards a more unilateral approach.13

- Some believe a trade war between the US and China is likely to materialise this year. Though the US only accounts for 13% of world trade, this may create an adverse impact on the global trading system.

- If the Trump Administration makes any drastic moves to restrict imports on steel and aluminium, among other products, countries may use the WTO to correct this measure. Whether the Trump Administration will cooperate is uncertain.14

6. Key Readings

Baldwin, R., Kawai, M. and Wignaraja, G. (2014). A World Trade Organization for the 21st Century: The Asian Perspective. Asian Development Bank Institute.

Geeganage, A. (2013). Sri Lanka’s Role in the World Trade Organization. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(1), pp.137-157.

Malith, D. and De Zylva, A. (2017). Implications of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement for Sri Lanka. [online] The Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. Available at: https://lki.lk/publication/implications-wto-trade-facilitation-agreement-sri-lanka/ [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

Overseas Development Institute (2017). The implications of WTO negotiation options for economic transformations in developing economies. Supporting Economic Transformation. [online] Available at: https://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/SET-WTO-Negotiations-Summary-Paper.pdf [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

Trade Policy Review Report by the Secretariat Sri Lanka. (2016). WTO Trade Policy Review Body. Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/s347_e.pdf [Accessed 17 Jan. 2018].

Wignaraja, G. and Collins, A. (2017). Why Sri Lanka Must Support the WTO at its Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires. [online] The Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. Available at: https://lki.lk/publication/why-sri-lanka-must-support-the-wto-at-its-ministerial-conference-in-buenos-aires/ [Accessed 12 Jan. 2018].

Notes

1 World Trade Organisation. (2018). What is the WTO?. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/whatis_e.htm [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

2 World Trade Organisation. (1995). AGREEMENT ESTABLISHING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/04-wto.pdf [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018]. Article XVI (4)

3 Ibid.

4 World Trade Organisation. (1994). General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/06-gatt_e.htm [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018]. Article XXIII:1

5 World Trade Organisation. (n.d.). Understanding on rules and procedures governing the settlement of disputes Annex 2 of the WTO Agreement. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dsu_e.htm [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018]. Article 3 (2)

6 Malith, D. and De Zylva, A. (2017). Implications of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement for Sri Lanka. [online] The Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. Available at: https://lki.lk/publication/implications-wto-trade-facilitation-agreement-sri-lanka/ [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

7 Office of the United States Trade Representative (2017). The President’s 2017 Trade Policy Agenda. [online] Available at: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2017/AnnualReport/Chapter%20I%20-%20The%20President%27s%20Trade%20Policy%20Agenda.pdf

8 Overseas Development Institute (2017). The implications of WTO negotiation options for economic transformations in developing economies. Supporting Economic Transformation. [online] Available at: https://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/SET-WTO-Negotiations-Summary-Paper.pdf [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

9 World Trade Organisation. (2018). WTO | Agriculture – Explanation of the agreement – Other Issues. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/ag_intro05_other_e.htm#peace_clause [Accessed 12 Jan. 2018].

10 World Trade Organisation. (2015). Briefing Note: Electronic Commerce. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/briefing_notes_e/brief_ecommerce_e.htm [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

11 World Trade Organisation. (2018). WTO | News – Speech – DG Roberto Azevêdo – MC11 Closing Ceremony. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/spra_e/spra209_e.htm [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

12 Ibid

13 Donnan, S. (2017). WTO faces an identity crisis as Trump weighs going it alone. The Financial Times. [online] Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/38c56f52-d9a5-11e7-a039-c64b1c09b482 [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

14 Swanson, A. (2018). Will 2018 Be the Year of Protectionism? Trump Alone Will Decide. The New York Times. [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/03/us/politics/2018-trump-protectionism-tariffs.html [Accessed 11 Jan. 2018].

Abbreviations

WTO World Trade Organization

GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

DSB Dispute Settlement Body

TPRM Trade Policy Review Mechanism

TRIPS Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

MFN Most-Favoured-Nation

TFA Trade Facilitation Agreement

MC11 11th Ministerial Conference of the WTO, held in 2017

*Pabasara Kannangara is a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). Daniella Kern was a Research and Communications Assistant at LKI. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own views. They are not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily represent or reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the authors are affiliated.