August 30, 2017 Reading Time: 14 minutes

Reading Time: 14 min read

Image Credit – bakhtiarzein / depositphotos

Anishka De Zylva*

This LKI Explainer, ‘The Paris Agreement on Climate Change and Sri Lanka’ explains key aspects of the Paris Agreement, which entered into force on 4 November 2016.1 It considers the implications of the Agreement for Sri Lanka’s policymakers in tackling climate change at home.

On 12 December 2015,2 195 states adopted the Paris Agreement. Both developed and developing states signed the Agreement for several reasons, including:

The main objectives of the Agreement are to:

China

European Union

“The EU and China are joining forces to forge ahead on the implementation of the Paris Agreement and accelerate the global transition to clean energy…in these turbulent times, shared climate leadership is needed more than ever.”

India

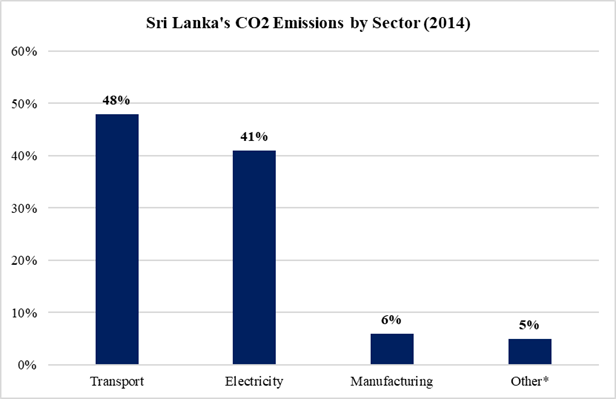

Figure 1

Climate-smart investment

Figure 2: Snapshot of IFC Analysis

Geopolitical relations

Climate Investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets: An IFC Analysis. (2016). Washington D.C.: International Finance Corporation. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/51183b2d-c82e-443e-bb9b-68d9572dd48d/3503-IFC-Climate_Investment_Opportunity-Report-Dec-FINAL.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

Frankel, J. (2015). A Fair, Efficient, and Feasible Climate Agreement. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/paris-climate-agreement-four-strengths-by-jeffrey-frankel-2015-12

Tay, S. (2017). Trump Let Down Needn’t Harm Asia’s Climate of Cooperation. South China Morning Post. http://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/2096712/trumps-paris-letdown-neednt-harm-asias-climate-cooperation

Tirpak, D., Brown, L. and Ronquillo-Ballesteros, A. (2017). Monitoring Climate Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Next Steps. World Resources Institute. http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/wri13_monitoringclimate_final_web.pdf

1 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9444.php

2 Ibid.

3 National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2017). NASA, NOAA Data Show 2016 Warmest Year on Record Globally. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-noaa-data-show-2016-warmest-year-on-record-globally

4 Harvey, F. (2017). Everything you need to know about the Paris climate summit and UN talks. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jun/02/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-paris-climate-summit-and-un-talks

5 Tay, S. (2017). Trump Let Down Needn’t Harm Asia’s Climate of Cooperation. South China Morning Post. http://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/2096712/trumps-paris-letdown-neednt-harm-asias-climate-cooperation

6 Carrington, D. (2017). ‘Spectacular’ drop in renewable energy costs leads to record global boost. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/06/spectacular-drop-in-renewable-energy-costs-leads-to-record-global-boost

7 United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9444.php

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). INDCs – Intended Nationally Determined Contributions. http://unfccc.int/focus/indc_portal/items/8766.php

17 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). Intended Nationally Determined Contributions. http://unfccc.int/focus/indc_portal/items/8766.php

18 United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2014). Copenhagen Climate Change Conference: December 2009. http://unfccc.int/meetings/copenhagen_dec_2009/meeting/6295.php

22 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2016). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf#page=17

23 United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Harvey, F. (2015). Paris climate change deal too weak to help poor, critics warn. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/14/paris-climate-change-deal-cop21-oxfam-actionaid

27 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (n.d.). Adoption of the Paris Agreement Draft decision -/CP.21. http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/cop_auv_template_4b_new__1.pdf

28 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). Climate Finance. https://www.unfccc.int/cooperation_and_support/financial_mechanism/items/2807.php

29 Harvey, F. (2015). Paris climate change deal too weak to help poor, critics warn. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/14/paris-climate-change-deal-cop21-oxfam-actionaid

30 Loris, N. and Tubb, K. (2017). 4 Reasons Trump Was Right to Pull Out of the Paris Agreement. The Heritage Foundation. http://www.heritage.org/environment/commentary/4-reasons-trump-was-right-pull-out-the-paris-agreement

31 The White House (2017). Readout of President Donald J. Trump’s Telephone Calls with Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, President Emmanuel Macron of France, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada, and Prime Minister Theresa May of the United Kingdom. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/06/01/readout-president-donald-j-trumps-telephone-calls-chancellor-angela

32 Harrington, R. (2017). Trump Withdrawing from Paris Agreement. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/trump-paris-agreement-climate-change-2017-6

33 Friedrich, J., Ge, M. and Pickens, A. (2017). This Interactive Chart Explains World’s Top 10 Emitters, and How They’ve Changed. World Resources Institute. http://www.wri.org/blog/2017/04/interactive-chart-explains-worlds-top-10-emitters-and-how-theyve-changed

34 Doyle, A. (2016). Trump win threatens climate funds for poor, a key to Paris accord. Reuters.com. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-climatechange-nations-idUSKBN1370BD

35 Davenport, C. (2016). Donald Trump Could Put Climate Change on Course for ‘Danger Zone’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/11/us/politics/donald-trump-climate-change.html?_r=0

36 Green Climate Fund. (2017). Resource mobilization. http://www.greenclimate.fund/how-we-work/resource-mobilization

37 Green Climate Fund (2017). Status of Pledges and Contributions made to the Green Climate Fund. http://www.greenclimate.fund/documents/20182/24868/Status_of_Pledges.pdf/eef538d3-2987-4659-8c7c-5566ed6afd19

38 Sinha, A. (2017). How Donald Trump’s withdrawal from Paris Agreement affects climate change goals – especially India’s. The Indian Express. http://indianexpress.com/article/beyond-the-news/how-donald-trumps-withdrawal-from-paris-agreement-affects-climate-change-goals-especially-indias-4685496/

39 Taylor, A. (2017). Why Nicaragua and Syria didn’t join the Paris climate accord. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/05/31/why-nicaragua-and-syria-didnt-join-the-paris-climate-accord/?utm_term=.8db57dbd7e3a

40 Ibid.

41 European Commission (2017). Commissioner Arias Cañete in China to strengthen climate and clean energy ties. http://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/news/commissioner-arias-ca%C3%B1ete-china-strengthen-climate-and-clean-energy-ties

42 Bruce-Lockhart, A. (2017). Top quotes by China President Xi Jinping at Davos 2017. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/chinas-xi-jinping-at-davos-2017-top-quotes/

43 World Economic Forum. (2017). President Xi’s Speech to Davos in Full. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/full-text-of-xi-jinping-keynote-at-the-world-economic-forum

44 Mauldin, W. (2015). China’s Xi Wants More Funds From Rich Nations in Climate Deal. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-xi-wants-more-funds-from-rich-nations-in-climate-deal-1448892347

45 China Daily (2015). China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund benefits developing countries. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/XiattendsParisclimateconference/2015-11/30/content_22557413.htm

46 Ibid.

47 European Commission (2017). Commissioner Arias Cañete in China to strengthen climate and clean energy ties. http://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/news/commissioner-arias-ca%C3%B1ete-china-strengthen-climate-and-clean-energy-ties

48 Boffey, D., Connolly, K. and Asthana, A. (2017). EU to bypass Trump administration after Paris climate agreement pullout. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/02/european-leaders-vow-to-keep-fighting-global-warming-despite-us-withdrawal

49 Government Italian Presidency Council of Ministers. (2017). Italy-Germany-France Declaration on US Announcement of Exit from the Paris Climate Agreement. http://www.governo.it/articolo/dichiarazione-italia-germania-francia-sullannuncio-degli-usa-delluscita-dallaccordo-di

50 Choi, D. (2017). How world leaders are reacting to Trump’s decision to leave the Paris climate agreement. Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/paris-climate-agreement-reaction-from-world-leaders-2017-6/#canadian-prime-minister-justin-trudeau-we-are-deeply-disappointed-1

51 Roy, S. (2017). Sushma Swaraj rebuts Donald Trump: Paris pact India ethos. The Indian Express. http://indianexpress.com/article/india/sushma-swaraj-rebuts-donald-trump-paris-pact-india-ethos-4690910/

52 Ibid.

53 The White House (2017). Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/06/01/statement-president-trump-paris-climate-accord

54 United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

55 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2014). Climate Finance. http://unfccc.int/cooperation_and_support/financial_mechanism/items/2807.php

56 Green Climate Fund. (n.d.). Portfolio dashboard. http://www.greenclimate.fund/what-we-do/portfolio-dashboard

57 Global Environment Facility. (n.d.). Funding. http://www.thegef.org/about/funding

58 The World Bank. (2017). Adaptation Fund. http://fiftrustee.worldbank.org/Pages/adapt.aspx

59 Climate Investment Funds. (n.d.). What We Do. https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/about

60 China Daily (2015). China South-South Climate Cooperation Fund benefits developing countries. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/XiattendsParisclimateconference/2015-11/30/content_22557413.htm

61 Asian Development Bank. (n.d.). 2016 Climate Change Financing. https://www.adb.org/climate-change-financing

62 The World Bank. (2017). World Development Indicators Data Bank. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

63 Fernandez, M. (2017). Sri Lanka hit by worst drought in decades. Aljazeera. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/01/sri-lanka-drought-170122092517958.html

64 Aljazeera. (2017). Sri Lanka floods leave 600,000 people displaced. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/05/sri-lanka-floods-leave-600000-people-displaced-170531132021197.html

65 Asian Development Bank. (2017). A Region at Risk: The Human Dimensions of Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific. https://www.adb.org/publications/region-at-risk-climate-change

66 Green Climate Fund. (2016). Project FP016. https://www.greenclimate.fund/-/strengthening-the-resilience-of-smallholder-farmers-in-the-dry-zone-to-climate-variability-and-extreme-events-through-an-integrated-approach-to-water-?inheritRedirect=true&redirect=%2Fprojects%2Fbrowse-projects

67 Global Environment Facility. (2017). Sri Lanka. https://www.thegef.org/country/sri-lanka

68 The Commonwealth (2016). Commonwealth hub to unlock billions in climate finance for developing countries. http://thecommonwealth.org/media/press-release/commonwealth-hub-unlock-billions-climate-finance-developing-countries

69 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2016). Unlocking Finance for Developing Countries Commonwealth Climate Finance Access Hub Opened. http://newsroom.unfccc.int/climate-action/new-commonwealth-hub-to-unlock-billions-in-climate-finance-for-developing-countries/

70 The Commonwealth (2016). Commonwealth hub to unlock billions in climate finance for developing countries. http://thecommonwealth.org/media/press-release/commonwealth-hub-unlock-billions-climate-finance-developing-countries

71 Government of Kenya (2012). National Climate Change Action Plan 2013 -2017. https://cdkn.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Kenya-Climate-Change-Action-Plan_Executive-Summary.pdf

72 Climate Change & Singapore: Challenges. Opportunities. Partnerships. (2012). Singapore: National Climate Change Secretariat, p.107. http://www.nea.gov.sg/energy-waste/climate-change

73 Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Government. (2017). The Australian Government’s Action on Climate Change. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/f29a8ccb-77ca-4be1-937d-78985e53ac63/files/factsheet-australian-government-action.pdf

74 Ministry of Environment (2017). The National Climate Change Policy of Sri Lanka. http://www.climatechange.lk/CCS Policy/Climate_Change_Policy_English.pdf

75 Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment (2016). National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change Impacts in Sri Lanka. Climate Change Secretariat, Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment. http://www.climatechange.lk/NAP/NAP For Sri Lanka_2016-2025.pdf

76 Brown, J., Cantore, N. and Willem te Velde, D. (2010). Climate financing and Development – Friends or foes? Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/5796.pdf

77 The Climate Change Secretariat Sri Lanka. (n.d.). About Us. http://www.climatechange.lk/About_us.html

78 Tirpak, D., Brown, L. and Ronquillo-Ballesteros, A. (2017). Monitoring Climate Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Next Steps. World Resources Institute. http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/wri13_monitoringclimate_final_web.pdf

79 Ibid.

80 Climate Investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets: An IFC Analysis. (2016). Washington D.C.: International Finance Corporation. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/51183b2d-c82e-443e-bb9b-68d9572dd48d/3503-IFC-Climate_Investment_Opportunity-Report-Dec-FINAL.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 Ibid.

84 Tirpak, D., Brown, L. and Ronquillo-Ballesteros, A. (2017). Monitoring Climate Finance in Developing Countries: Challenges and Next Steps. World Resources Institute. http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/wri13_monitoringclimate_final_web.pdf

85 Ibid.

86 The Editorial Board. (2017). China and India Make Big Strides on Climate Change. The New York Times.

87 Ibid.

88 Coca, N. (2017). Asia and the Fall of Coal. The Diplomat. http://thediplomat.com/2017/06/asia-and-the-fall-of-coal/

89 The Editorial Board. (2017). China and India Make Big Strides on Climate Change. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/22/opinion/paris-agreement-climate-china-india.html

90 Brodie, C. (2017). India will sell only electric cars within the next 13 years. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/05/india-electric-car-sales-only-2030/

*Anishka De Zylva is a Research Associate at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. The author acknowledges Ashvin Perera and Dinuka Malith for their research assistance. The research included in this Explainer was supported by the John Keells Holdings PLC. The opinions expressed in this Explainer, and any errors or omissions, are the author’s own.