May 1, 2020 Reading Time: 8 minutes

Reading Time: 8 min read

Image Credits: Glenn Carstens-Peters/Unsplash

Chattalie Jayatilaka*

Digital diplomacy is an emerging phenomenon that has fundamentally altered the way that governments communicate and negotiate with each other and with their people. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, this has been demonstrated like never before. The restriction of international travel and movement within countries has shown that the adoption and implementation of digital diplomacy in Sri Lanka is imperative. Digital diplomacy has been used interchangeably with other terms such as e-diplomacy, cyber-diplomacy, or twiplomacy (referring to the Twitter presence of states, government leaders, and embassies).1 The influence of digital diplomacy on ideas which influence people’s actions and the networks which carry these ideas has been monumental. This LKI Policy Brief aims to understand how this phenomenon has impacted international relations thus far, and what actions Sri Lanka can take to benefit.

The largest element of foreign policy is the ability of a country to achieve policy objectives in the name of national interest and diplomacy is the preferred method. Diplomacy allows states to articulate their foreign policy objectives and coordinate their effort through dialogue and negotiations in order to influence the behavior and subsequent decisions of foreign governments.2 Yet the revolution of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has fundamentally changed the face of diplomacy and how countries communicate with each other, their populace, and non-state actors. This revolution of ICT has led to an emergence of digital diplomacy which has in turn revolutionized diplomatic engagement.3 The previous held status quo of government to government engagement has transformed, and social media has created an increase in people to government and people to people engagement. While the effects of this relatively new phenomenon are still being studied, it is clear that there are certain consequences on international relations, and that Sri Lanka stands to benefit enormously.

Digital diplomacy is the most recent phenomenon in foreign relations, and has been interpreted and defined in a multitude of ways. For the purposes of this Policy Brief, digital diplomacy refers to the use of social media platforms by official state bodies of a country to achieve its foreign policy goals, image and maintain its reputation.4 These platforms are typically run in the name of the state by official representatives such as members of the Ministry of Foreign Relations, officials, diplomats, or even Heads of State. Digital diplomacy creates a massive opportunity for governments to engage directly with a wider audience of civil society as well as with other governments, and influential individuals.5 Countries have embraced e-diplomacy and use platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and more to communicate. There are even dedicated offices in various countries for digital diplomacy such as the US Office of eDiplomacy and the British Office of Digital Diplomacy.6 But how has digital diplomacy changed the face of how international relations is overall conducted?

Figure 1: UN Member States on Social Media Platforms.

Source: Twiplomacy Study, 2018

As digital diplomacy is a relatively newer trend, it may be too early to conclusively analyze its impact on international relations, but this Policy Brief will attempt to summarize key conclusions that experts have made over the recent years. The primary effect of digital diplomacy on international relations is the most crucial; it has multiplied and amplified the voices of those involved in international policy making and their interests which has complicated the decision making processes of states.7 Digital diplomacy has effectively reduced the exclusive control which states hold on policy and created a platform for people to express their opinions directly and in real time. The creation of a global platform through digital diplomacy has shifted the network of diplomacy from paper and real world onto a virtual network of digital connections. The physical barriers to decision making have disappeared leading to easier access to information, and created virtual structures for implementation.8

Furthermore, digital diplomacy has accelerated the dissemination of information, particularly during various crises. However, this incredibly instantaneous spread of information does not discriminate on accuracy, which has an impact on its consequences and handling. This has become particularly evident during the COVID-19 (Coronavirus outbreak) as multiple countries have used social media to communicate with citizens and the world as many are put into quarantine.9 In addition, digital diplomacy has also allowed for diplomatic services to be delivered faster and more cost effectively to their own citizens as well as to those of other countries which has allowed embassies to become more efficient, working faster with less people.10 While there are many benefits to digital diplomacy, it does come with a multitude of risks which include information leakage, hacking, and user anonymity.11

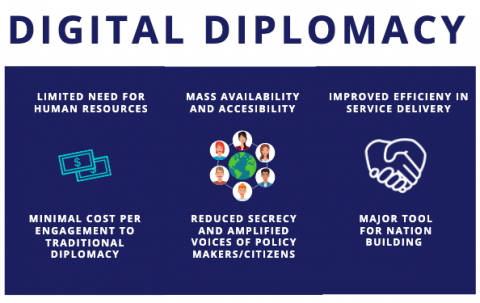

Figure 2: Advantages of Digital Diplomacy

Source: Digital Diplomacy: India’s Increasing Digital Footprints

Despite these risks, digital diplomacy has changed the foundation of how ideas spread and how networks have functioned in international relations, which has brought the world closer together and led to more effective foreign policy. Many countries have already been using digital diplomacy to great effect. In 2014, Germany turned to digital platforms to crowd source opinions and new ideas for their foreign policy review for that year.12 In 2012, Russian President Vladimir Putin designated digital diplomacy as one of the most effective foreign policy tools and encouraged diplomats to use social media platforms.13 In India, the Ministry of External Affairs used Twitter to evacuate 18,000 Indian citizens from Libya during the civil war in 2011, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has called on his ambassadors to “remain ahead of the curve on digital diplomacy”.14 States which do not engage in digital diplomacy risk falling behind, and yet it seems that low to middle income countries may be able to massively benefit from this phenomenon.

ICTs offer less developed countries an opportunity to leapfrog the industrialization state and cultivate their economies into high value-added information economies which have the potential to compete with advanced economies on the global market.15 Digital diplomacy is no different, and the potential for Sri Lankan digital diplomacy which is still in its infancy is enormous. Currently, the Government of Sri Lanka engages in limited digital diplomacy, and leaves it to the discretion of the individual or organization.16 The main pages which engage in digital diplomacy for Sri Lanka are the twitter pages of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), found at @MFA_SriLanka, and the Minister of Foreign Relations, Dinesh Gunawardena (@DCRGunawardena). Both of these pages tweet images, text, and notices daily. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka does not currently have a standardized digital diplomacy strategy, plan, or policy in place.

Diplomacy is a competitive business, unlike other governmental departments, and Sri Lanka must continue to adapt and evolve as the industry changes or we risk becoming ineffective in our services. Diplomacy is one of the most powerful soft power tool’s a country can employ and further research is necessary to implement a Sri Lanka specific plan to success.17 Its proficient use would allow Sri Lanka the chance to actively cultivate our own narrative and image to the world through platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

It is too soon to understand the full effect of digital diplomacy over the past decade on international relations, but it is very clear that the advancement of technology has led to a degree of digitization that has transformed the face of modern diplomacy. Through this phenomenon, Sri Lanka is able to cultivate a wider digital presence, create e-governance services to aid citizens, and increase efficiency at little cost. Governments must take greater account of the influence of digital diplomacy in international relations in the future and make full use of these opportunities or risk becoming ineffective.

1Lufkens, M. (2018). Twiplomacy Study 2018 – Twiplomacy. Twiplomacy. [Online] Available at: https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2018/ [Accessed 20 January 2020].

2Ross, A. (2011). Digital Diplomacy and US Foreign Policy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 6(3-4): 451-455.

3Ibid.

4Manor, I. & Segev, E. (2020). America’s selfie: how the US portrays itself on its social media accounts. In: C. Bojla & M. Holmes. eds. Digital Diplomacy Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge, pp.89-108.

5Supra note 2.

6Verrekia, B. (2017). Digital Diplomacy and Its Effect on International Relations Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. [Online] Available at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3619&context=isp_collection [Accessed 21 January 2020].

7Sotiriu, S. (2015). Digital diplomacy: Between promises and reality. In C. Bjola & M. Holmes. eds. Digital Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 33–51.

8Ibid.

9De la Garza, A. (2020). How Social Media Is Shaping Our Fears of — and Response to — the Coronavirus. Time Magazine. [Online] Available at: https://time.com/5802802/social-media-coronavirus/ [Accessed 20 January 2020].

10Schwarzenbach, B. (2015). Twitter and diplomacy: How social media revolutionizes interaction with foreign policy. DiploFoundation. [Online] Available at: https://www.diplomacy.edu/twitter-and-diplomacy-how-social-networking-changing-foreign-policy [Accessed 20 January 2020].

11Westcott, N. (2008). Digital Diplomacy: The Impact of the Internet on International Relations. Research Report 16. Oxford Internet Institute. [Online] Available at: https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/archive/downloads/publications/RR16.pdf [Accessed 20 January 2020].

12Cave, D. (2015). Does Australia Do Digital Diplomacy? The Interpreter by the Lowy Institute. [Online] Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/does-australia-do-digital-diplomacy [Accessed 8 February 2020].

13Permyakova, L. (2012). Digital diplomacy: Areas of work, risks and tools. [Online] Available at: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/digital-diplomacy-areas-of-work-risks-and-tools/ [Accessed 21 January 2020].

14Lewis, D. (2014). Digital Diplomacy. Gateway House. [Online] Available at: https://www.gatewayhouse.in/digital-diplomacy-2/ [Accessed 20 January 2020].

15te Velde, D. (2020). Economic Transformation – Lessons From International Experience. Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. [Online] Available at: https://lki.lk/publication/takeaways-dr-dirk-willem-te-velde-on-economic-transformation-lessons-from-international-experience/

[Accessed 20 January 2020].

16Gunawardene, N. (2016). Network Diplomacy: Is Sri Lanka Ready? Echelon. [Online] Available at: https://echelon.lk/network-diplomacy-is-sri-lanka-ready [Accessed 22 January 2020].

17Mcclory, J. (2019). The Soft Power 30: A Global Ranking of Soft Power 2019. 1st ed. Portland. [Online] Available at: https://softpower30.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Soft-Power-30-Report-2019-1.pdf [Accessed 22 January 2020].

18Government of Sri Lanka (2012). Sri Lanka Electronic Travel Authorization. [Online] Available at: https://www.eta.gov.lk/slvisa/visainfo/center.jsp?locale=en_US [Accessed 5 February 2020].

19EconomyNext. (2020). Contact Sri Lanka Portal to Help Overseas Sri Lankans Launched During Coronavirus Crisis. [Online] Available at: https://economynext.com/contact-sri-lanka-portal-to-help-overseas-sri-lankans-launched-during-coronavirus-crisis-62344 [Accessed 22 January 2020].

20Cinnamon Hotels. (2019). Bring a Friend Home. [Online] Available at: https://www.bringafriendhome.com/ [Accessed 3 April 2020].

21Adesina, O. (2017) . Foreign policy in an era of digital diplomacy. Cogent Social Sciences. 3(1).

22Sanchez, W. (2018). The Rise Of The Tech Ambassador. Diplomati Courier. [Online] Available at: https://www.diplomaticourier.com/posts/the-rise-of-the-tech-ambassador [Accessed 21 April 2020].

23Hasangani, S. (2020). Tech Giants, ‘TechPlomacy’ and Mitigating Online Radicalization: Lessons for Sri Lanka. Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. [Online] Available at: https://lki.lk/publication/tech-giants-techplomacy-and-mitigating-online-radicalization-lessons-for-sri-lanka/ [Accessed 21 April 2020].

*Chattalie Jayatilaka was a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. The opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.