December 24, 2019 Reading Time: 14 minutes

Reading Time: 14 min read

Image Credits: João Silas/Unsplash

Nilupul Gunawardena and Pabasara Kannangara*

With a population of over 1.3 billion in 2019, the African region is a diverse and dynamic grouping of countries with a combined Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of over USD 6 trillion. Sri Lanka’s diplomatic engagement with the region dates back to the 1960’s, and has many strengths. However, there are a number of areas where Sri Lanka could improve its existing economic and diplomatic linkages.

This Policy Brief will look at ways Sri Lanka can develop and expand its economic links with countries in the African Region.

Sri Lanka’s interactions with Africa are as old as the country’s history. African visitors were frequent visitors to Sri Lanka in ancient times, including to the courts of various Kings. Descendants of these early settlers still live in Sri Lanka today, as distinctive communities, concentrated mainly in areas such as Sirambiadiya, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Negombo. These communities try to preserve their culture, through their culture, cuisine, and particularly their music. This has made a distinct mark on Sri Lankan culture and contributed to its diversity.

Sri Lanka and Africa have also been there for each other during times of strife. Under the British rule, members of the Kandyan nobility, including Ehelepola Maha Adikaram, the Prime Minister of the Kandyan Kingdom were exiled to Mauritius. Similarly, the exiled Egyptian leader Ahmed Orabi and his comrades arrived in Ceylon in 1883 and remained for 18 years. Sri Lanka also share a commonality with many African States in respect of its legal system – The Roman-Dutch Law. Like Sri Lanka, many African States including Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Eswatini, and South Africa derives its legal framework from the principles of the Roman-Dutch Legal System.

In addition to these historical links, Sri Lanka also maintains significant economic ties with the African region, though there is scope for further growth. Bilateral trade amounted to almost USD 500 million in 2018, compared to around USD 150 million in 2009, with Sri Lanka’s key export to Africa including tea, rubber, and electrical equipment. In addition, South Africa is currently Sri Lanka’s major source of coal imports, accounting for most of the country’s imports from the region. Investment, tourism, and migration flows have also grown in recent decades, though they remain small in terms of total flows to Sri Lanka.

This Policy Brief will discuss Sri Lanka’s existing relationships with Africa, as well as the opportunities and challenges to strengthening this relationship. It also offers some policy suggestions on strengthening Sri Lanka relations with the region.

Since independence, Sri Lanka has strengthened diplomatic ties with Africa through several multilateral fora. These include the 1955 Bandung Conference and the 5th Non-Aligned Movement Summit held in Colombo in 1976. Sri Lanka’s support for the independence of African states clearly manifested during the tenure of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Throughout her regime, Prime Minister Bandaranaike reiterated her support and that of all Non-Aligned Movement states, for the African people’s liberation struggle. Sri Lanka was also at the forefront of supporting the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

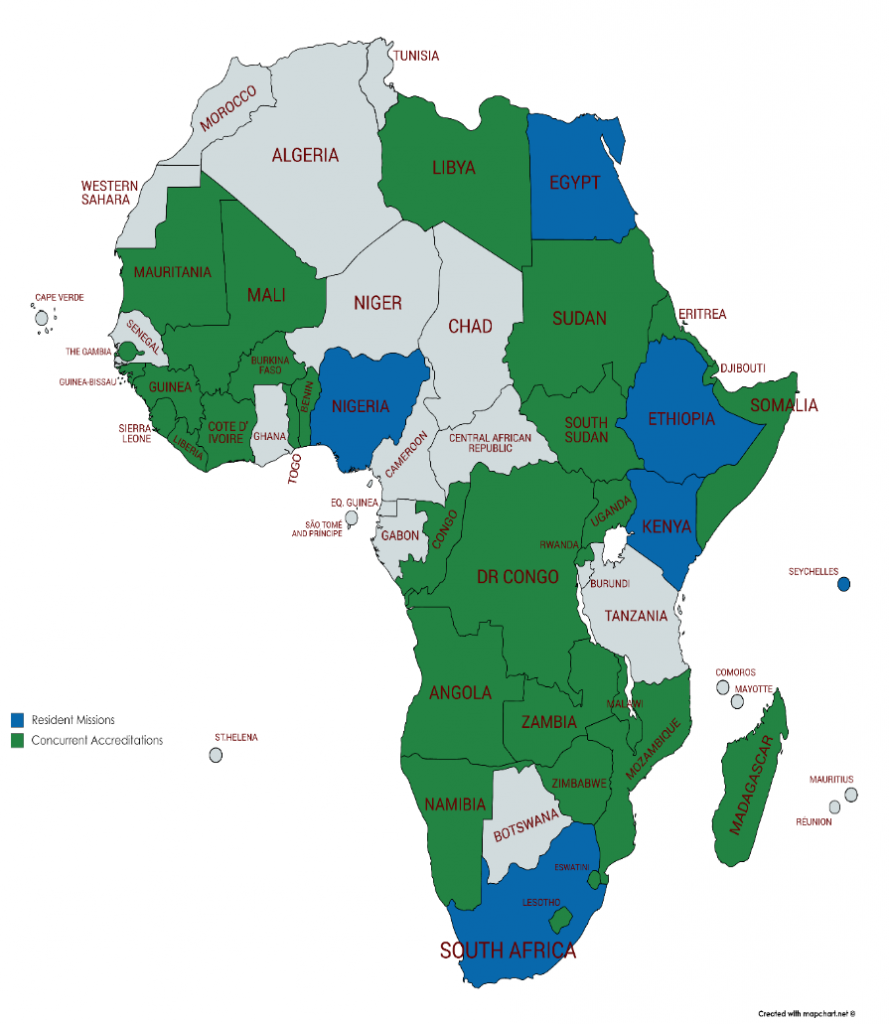

Today, Sri Lanka enjoys strong diplomatic relations with 45 African States and has resident missions in six of these, specifically Nigeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Seychelles, and South Africa. (See Figure 1.) Furthermore, Sri Lanka has established a large number of consulates, concurrently accredited from these resident Missions. Additionally, Sri Lanka has appointed 10 Honorary Consuls in the African Region.

In 1957, Egypt was the first African country to open a diplomatic mission in Sri Lanka. Former President of Egypt, the late Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein took this initiative following Sri Lanka’s strong support to Egypt during the Suez Canal crisis in 1956. Thereafter Libya, South Africa, and Seychelles opened missions in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, a large number of African states are concurrently accredited to Sri Lanka through resident missions in New Delhi and Kuala Lumpur.

Over the years many inbound and outbound high-level visits have taken place between Sri Lanka and Africa. The President of Sri Lanka was represented at the inauguration of President Nelson Mandela in 1994, and in 1996 the then Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar led a Sri Lankan delegation of high-ranking officials from travel, trade and business, to South Africa. Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister, Prof. G. L. Peiris also visited South Africa in 1997 as part of a process of consultations to draw on the experience of constitution making in multi-ethnic societies, while drafting Sri Lanka’s new constitution.

As witness to Sri Lanka’s growing relations with Africa, over the last decade there have been three state visits by the Heads of State from Eswatini, Seychelles, and Uganda to Sri Lanka. During the recent past, a number of Sri Lankan Ministers have also undertaken official visits to many African states including Botswana, Burkina Faso, Benin, Egypt, Republic of Congo, Mauritius, Djibouti, Libya, Kenya, Mauritania, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal Seychelles, South Africa, and Uganda. These visits indicate the importance the government of Sri Lanka attaches to its African counterparts.

Figure 1: Diplomatic Presence in Africa

Source: LKI, Data – Africa Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In 2014, Sri Lanka obtained accreditation status in the African Union (AU) as a non-member State and opened a resident Mission in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2017.1 As the home of the AU headquarters, Addis Ababa provides a platform for engagement with all 55 member states.

While Sri Lanka does not have any free trade agreement or bilateral investment treaties with countries in the African region, bilateral cooperation has been supported through various agreements, MoUs, Bilateral Joint Commissions, and Partnership Forums. These include agreements with Eswatini, Uganda, and Seychelles in a number of different fields. Similarly, Sri Lanka has provided various forms of aid to a number of African states. For example, the Government of Sri Lanka granted USD 1.5 million towards the upgrading of the Masulita Training Institute in Uganda, 2 which will be renamed the Sri Lanka-Uganda Friendship Vocational Training Centre. Sri Lanka has also donated 10,000 mt. tons of rice to famine-stricken people in the Eastern Africa region in recent years with the assistance of the World Food Programme. And in 2012, people affected by an explosion in Brazzaville received Rs. 3.3 million worth of medical supplies from the Government of Sri Lanka.3

Sri Lanka’s economic engagement with Africa is currently at a nascent stage and there is significant potential to increase trade, investment, and people-to-people ties in a manner beneficial for Sri Lanka. The region is becoming an increasingly important part of the global economy and presents a potentially lucrative economic opportunity for Sri Lanka. It is home to 1.2 billion people, spread over 54 independent countries, and accounted for around 5.0% of both global GDP (at PPP exchange rates), and world trade in 2018. Regional GDP growth averaged 3.2% between 2015 and 2018, and the African Development Bank expects it to pick up to 4.0% in 2019-20.4 This would make it one of the fastest growing regions in the world.

3.1 Trade

Sri Lanka’s trade with the African region has grown steadily over recent years, though it remains a small part of the country’s total trade. (See Figure 2). In 2018, bilateral trade in goods amounted to USD 466 million, accounting for just 1.4% of Sri Lanka’s total goods traded. Bilateral trade has for the most part been in favour of Sri Lanka, with the country generally maintaining a modest trade surplus with the region. For example, in 2018 Sri Lanka’s exports to Africa amounted to USD 249 million (2.1% of Sri Lanka’s total exports), while imports from the region stood at USD 217 million (1.1% of Sri Lanka’s total imports). Tea, rubber, electrical machinery, and paper account for 63% of total goods exported by Sri Lanka to Africa, while minerals and fuel, edible fruit, beverages, and perfumes make up over 80% of Sri Lanka’s imports from Africa.

Figure 2: Sri Lanka’s Trade with Africa

Source: Trade Map and IMF Direction of Trade Statistics

*2018 data are estimates based on partial data from IMF DOTS

3.2 Major Markets: Exports and Imports

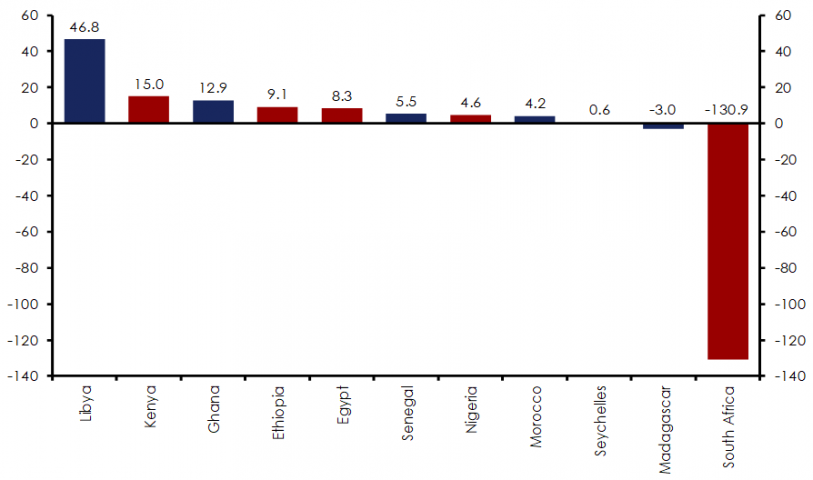

Despite having an overall trade surplus with the region, bilateral trade is concentrated with a few countries. In fact, 11 out of the 54 African countries account for 85% of Sri Lanka’s total trade with the region. Libya is the largest market for Sri Lanka’s exports to the region, boasting a trade surplus of USD 46.8 million in 2018. In contrast, Sri Lanka has posted a relatively large trade deficit with South Africa. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Sri Lanka’s Goods Trade Balance with Major African markets* (US$ Millions, 2018)

*These 11 countries account for around 85% of the value of Sri Lanka’s total trade with the African region

*These 11 countries account for around 85% of the value of Sri Lanka’s total trade with the African region

Source: IMF, Direction of Trade Database.

Accessed September 2019.

As the largest market for Sri Lankan goods in Africa, Libya was the destination for USD 46.9 million of exports in 2018 (See Figure 4), which is equivalent to roughly 19% of Sri Lanka’s total exports to the region. Much of these exports are packaged tea. In fact, Libya is one of five major markets for Sri Lankan tea in the region, accounting for 52% of tea exports to Africa in 2017. South Africa is Sri Lanka’s second largest export destination in Africa, accounting for USD 40.9 million exports in 2018. This mainly consisted of bulk tea, apparel, and rubber products.

South Africa is Sri Lanka’s largest source of imports in the region, accounting for 80% of total imports from Africa. (See Figure 5.) This is almost entirely composed of coal imports. Indeed, South Africa has become Sri Lanka’s primary source of coal since 2015, accounting for 97% of coal imports in 2018. This reflects a sharp decline in coal imports from Indonesia and is crucial for the operation of Sri Lanka coal-based electricity plants.

Figure 4: Sri Lanka’s Goods Exports to Major African Markets * (US$ Millions, 2018)

Figure 5: Sri Lanka’s Goods Imports to Major African Markets* (US$ Millions, 2018)

Source: ITC, TradeMap.

Accessed September 2019.

It is also noteworthy that some countries where Sri Lanka has resident missions, have minimal trading relations with Sri Lanka. For example, exports to Seychelles amounted to just USD 3.9 million in 2018, while exports to Nigeria were only USD 5.6 million in the same year. What’s more, Sri Lanka’s imports from these two countries are less than USD 1.5 million. Similarly, Ethiopia, and Kenya have relatively small markets for Sri Lankan goods. Total trade for these countries amounted to only USD 35 million in 2018.

3.3 Foreign Direct Investment

Africa is not a major source of foreign direct investment (FDI) for Sri Lanka. In fact, between 2014 to 2018, Sri Lanka received roughly USD 197.6 million in investments from Africa, accounting for only 3.6% of total FDI received during this same period. The majority of this FDI was from Mauritius, which accounted for USD 188 million of inward FDI between 2014 to 2018.5

As evidenced by the low levels of investment, limited engagement can be seen with African businesses in Sri Lanka. However, there is some anecdotal evidence of increased engagement. In 2017, SPAR Group Ltd, a food retail company originating from South Africa begun operations in Sri Lanka via a joint venture with Ceylon Biscuits Ltd. Catering to the local market, SPAR has expanded quite rapidly, with 3 retail stores already in operation and reaching close to a million euros in retail sales in 2018.6

In terms of outward investment, there are a number of local businesses from various sectors that have entered the African market. Hirdaramani Apparel and Hela Clothing have both opened manufacturing facilities in Ethiopia due to low wages and favourable tax incentives. Similarly, Sierra Cables started operations in 2016 in Kenya, in order to supply to the East African market. There is also some local interest in the energy market in Africa. VS Hydro and Hemas Power (subsidiaries of Hemas) have invested in hydropower projects in Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda. A local IT solutions company, hSenid, has also expanded operations to Africa.

3.4 Tourism and Migration

Sri Lanka received roughly 11,362 tourists from Africa in the first eight months of 2019 7, accounting for less than 1.0% of total arrivals during this period. The top three source markets were South Africa (4,233), Egypt (2,245), and Kenya (915). In comparison, Maldives received 15,354 tourists from Africa in 2018 (1.0% of total arrivals), while India received 318,023 in 2017 (3.2% of total arrivals). This suggest that there is significant scope to grow inbound tourism from Africa.

In terms of outward migration, 1,507 Sri Lankan’s departed for employment in the region in 2017.8 This was equivalent to 0.7% of total departures from Sri Lanka. Within the region, the Seychelles received the highest number of Sri Lankan workers accounting for 56% of total departures to Africa. This was followed by Mauritius and Uganda. The majority of departures were for skilled labour and available data suggests that most migrant workers are employed in the energy, gem, and hospitality sectors.

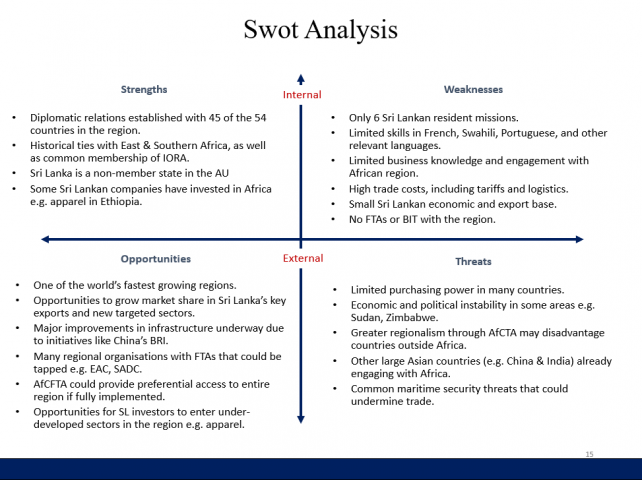

Despite efforts to improve Sri Lanka’s economic relationship with Africa, there are many gaps, including, lack of quality infrastructure, limited knowledge of markets among Sri Lankan businesses and high trade costs. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities & Threats (SWOT) analysis is a useful tool to summarise the key issues and (Figure 6) provide an overview of Sri Lanka-Africa ties.

Figure 6: SWOT Analysis of Sri Lanka-Africa Ties

4.1 Strengths and Opportunities

The main strengths of Sri Lanka’s ties with Africa include its strong diplomatic presence in the region, covering 45 of the 54 countries. This is further strengthened by Sri Lanka’s deep historical ties with East and Southern Africa, as well as common memberships of various international and regional institutions such as the Indian Ocean Regional Association (IORA). Sri Lanka is also a non-member state of the African Union, which is likely to open doors to further economic and political engagement. In addition, while trade with the region is relatively low, some apparel companies have successfully invested in manufacturing facilities in Africa.

In terms of opportunities, Africa is one of the world’s fastest growing regions, with a population of 1.3 billion. Its working-age population alone is expected to grow from 705 million in 2018 to nearly 1 billion in 2030. There is ample opportunity for Sri Lanka to tap into new markets and grow market share in targeted sectors. Many countries across the region are also making an effort to address their infrastructure constraints through initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This is likely to reduce trade costs and therefore facilitate more trade. In addition, trade agreements between African countries and other key markets, as well as the newly enforced African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), could increase access to new markets and create more opportunities for potential Sri Lankan investors.

AfCFTA entered into force on 30 May 2019 for the 24 countries that have deposited their instruments of ratification. The main objectives of the agreement is to create a single continental market for goods and services, with free movement of business persons and investments, and thus pave the way for accelerating the establishment of the Customs Union. While implementation is a significant challenge, once fully in force AfCFTA will cover a market of 1.2 billion people, 60 percent of whom are below the age of 25 years. Indeed, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa has estimated that the agreement could raise intra-African trade by 15% to 25%, or USD 50 billion to USD 70 billion, by 2040.9 For the time being, the agreement is only open to African Union member states, but an integrated trading zone would present a much more attractive option for outward investment.

4.2 Weaknesses and Threats

Despite these opportunities, there are still a number of constraints and risks that could arise. One major weakness is high trade costs, due to the lack of quality infrastructure. While quality infrastructure is needed, financing has remained an issue. Even accounting for initiatives like the BRI, financing for African infrastructure falls short by between USD 68 billion to 108 billion per year according to the African Development Bank. Limited quality infrastructure often leads to high transport costs. These costs roughly add up to 40% to the cost of doing business. KPMG estimates that transport costs in Africa are at least 50-175% higher than other parts of the world, crippling Africa’s ability to be globally competitive and depressing intra-regional trade.

In addition, limited connectivity and differences in culture have to some extent been a challenge. Despite sharing an ocean with Africa, there is still a sizeable distance between Sri Lanka and the region. As such, networking and establishing relations with local counterparts may prove to be difficult. Sri Lanka also doesn’t have any FTAs or BITs with African countries, which may mean that in some cases, there are limited incentives to engage in trade with these countries. In addition, the differences in culture and business ethics, as well as limited knowledge and in some cases, the negative perception of the region, may discourage some from engaging in business.

In terms of risks, most countries in this region are often disadvantaged by economic and political uncertainty and limited purchasing power, which may discourage potential investors. The region also faces a number of traditional and non-traditional maritime security threats, which have been growing more pressing in recent years. Greater regionalism though initiatives such as AfCFTA could also led to extra-regional markets like Sri Lanka losing out as trade barriers are reduced between African countries.

Sri Lanka’s ambition to be an economic hub in the Indian Ocean hinges on favourable growth of its relations with other Indian Ocean economies and flourishing trade routes. As part of this, Sri Lanka needs to invest in building upon its nascent linkages with economies in Africa

This should be business led and, given the significant challenges to operating in many African markets and high trading costs, will take time. Nonetheless, a number of Sri Lankan companies have already made significant inroads in East Africa, particularly in apparel and some industrial sectors. Sri Lanka’s diplomatic missions in the region should provide greater support to these efforts and promote investment in other promising sectors, particularly in countries where there are resident ambassadors. One example is the energy generation sector. Many East and Southern African nations are investing heavily to meet the energy demands of their rapidly developing economies and a number of Sri Lankan companies have started to explore this area. For instance, LAUGFS gas is looking at the possibility of providing liquid natural gas as cooking fuel in Kenya, after the government prohibited logging. And in Ethiopia, Venora Lanka Power Panels (Pvt.) has begun supplying solar panels to the local market.

Similarly, Sri Lanka’s missions in the most important tourism markets in the region, notably South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt, should engage in greater targeted promotion. These countries have growing middle classes who are increasingly considering various international travel destinations. Sri Lanka’s missions could partner with tour operators to promote the country as an attractive destination and ensure that packages are tailored to the local market. For example, Sri Lanka could focus on niche markets such as budget package holidays in particular markets.

To ensure strong diplomatic ties, and therefore favourable conditions for the growth economic relations, Sri Lanka may also want to consider a focused aid program with a number of African economies. The Sri Lankan government’s fiscal constraints will mean that this remains small for the time being, but targeted grants and support for training in areas such as health and education would help to generate significant good will, and create a strong basis for future South-South cooperation. Sri Lanka should also explore upgrading ties with major regional organizations e.g. East African Community, Southern African Development Community through FTAs with these regional groupings to gain greater market access.

Table A.1: Key Indicators for Africa Region

Read the DailyFT article on Revitalised Africa Policy here.

1Jayetilleke, R. (2019). Ehelepola Maha Adikaram of the Kandyan Kingdom. [Online] Daily News. Available at: http://archives.dailynews.lk/2005/04/23/fea10.htm

[Accessed 20 September 2019].

2Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka. (2019). Sri Lanka Opens a Resident Mission in Ethiopia. [Online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/slemb-ethiopia/ [Accessed 20 September 2019].

3Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka. (2019). President Opens a New Sri Lankan HC in Uganda. [Online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/ta/4153-president-opens-new-sri-lankan-hc-in-uganda/

[Accessed 20 September 2019].

4Asian Tribune (2019). Sri Lanka’s expanding relations with Africa. [Online] Available at: http://www.asiantribune.com/node/62815 [Accessed 20 September 2019].

5Central Bank of Sri Lanka. (2019). Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2018. [Online] Available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/economic-and-financial-reports/annual-reports/annual-report-2018 [Accessed 20 September 2019].

6Sri Lankan Tourism Development Authority. (2019). Tourist Arrival Report August 2019. [Online] Available at: http://www.sltda.lk/monthly-tourist-arrivals-reports-2019 [Accessed 20 September 2019].

7Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment. (2019). Annual Statistical Report of Foreign Employment – 2017. [Online] Available at: http://www.slbfe.lk/file.php?FID=489 [Accessed 20 September 2019].

8United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2019). African Trade Agreement: Catalyst for Growth | United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. [Online] Available at: https://www.uneca.org/stories/african-trade-agreement-catalyst-growth [Accessed 20 September 2019].

9We Build Value. (2019). Trans-African Highway: Nine New Highways Under Construction – Salini Impregilo Digital Magazine. [Online] Available at: https://www.webuildvalue.com/en/infrastructures/trans-african-highway-roads-and-railways-to-make-cargo-move.html [Accessed 20 September 2019].

*Nilupul Gunawardena is a Research Fellow at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. Pabasara Kannangara is a Research Associate at LKI. The authors acknowledge with appreciation comments given by Foreign Secretary Ravinatha Aryasinha, Additional Secretary P.M. Amza, Ambassador Himalee Arunatilake (Former Director General of Africa Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka), Mr. Thulan Bandara, Assistant Director, Africa Divisions, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka and other officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka. The authors would also like to extend their thanks to the attendees of the Sri Lanka-Africa Stakeholder meeting, held on 27th September 2019 at LKI. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own views. They are not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily represent or reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the authors are affiliated.