February 5, 2019 Reading Time: 17 minutes

Reading Time: 17 min read

Image Credit: Boarding2Now/depositphotos

Farah Ibrahim*

Following elections in 2018, the government of the Maldives is transitioning into a new administration, with the international community refocusing their attentions on this administration. This Policy Brief examines the relationship between Sri Lanka and the Maldives as it is and suggests areas for improvement.

Early this year, the newly-elected President of the Maldives, during an unofficial visit to Sri Lanka, reaffirmed the value of Maldives-Sri Lanka relationship based on the number of Maldivians living in Sri Lanka, the long diplomatic history and the economic contribution of Sri Lankan businesses in the Maldives.1

“Good fences make good neighbours” is the old proverb in Robert Frost’s poem about two neighbours debating whether the wall between their properties improves or hurts their relationship. One argues that the wall reduces conflict by denoting clear territorial responsibility, while the other declares friendly neighbours have few barriers between them. It is an argument prevalent among neighbouring nations. The terms ‘closest allies’ and ‘special relationships’ are reserved for nation states with close economic, diplomatic and security ties. Blocs like NAFTA, the EU, ASEAN, based on geographic proximity, have been especially vital to the regional prosperity and security of the member states.

The island economies of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, separated by 1035 kilometres of Indian Ocean, can never argue over physical walls, but the relationship can be measured by the degree of cooperation and openness between them. Relatively little research has been conducted on the Sri Lanka-Maldives relationship and as the Maldives transitions into a new government following elections in November 2018, it is worth exploring the depth of this relationship and consider areas of improvement. This Policy Brief attempts to examine the Sri Lanka-Maldives relationship through the prisms of diplomatic relations, security relations, in the context of regional powers and economic ties.

The Maldives established diplomatic relations with Sri Lanka on the day of its independence in 26 July 1965. The Embassy of the Maldives in Sri Lanka was opened the same day.2 Sri Lanka has an embassy in Malé.

Since then, diplomatic ties continued to strengthen. In 1981, the Maldives and Sri Lanka were among the seven founding members of the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).3

In 1984, the Maldives and Sri Lanka formed a joint commission under the Agreement on Economic and Technical Cooperation, further cementing ties. Six Joint Sessions have been held over the years. The last of which was held in 2017 and was resided by the respective Ministers of Foreign Affairs of both nations. The areas of discussion4—economic, education, tourism, fisheries, consular and community issues, human resource development, health, legal and law enforcement, encompass a wide range of common interests and signal a desire to deepen ties across a broad of economic and social sectors. The 2017 session culminated with the decision to move ahead concluding a Joint Task Force on Tourism, and forming a Joint Task Force on Trade.5

In addition to these Joint Sessions, a measure of the diplomatic relationship is the number of high-level bilateral visits conducted between the states. Over the last three years, there were five high-level bilateral diplomatic visits between the Maldives and Sri Lanka. In comparison, the tally of visits6 by other major allies is, one visit (by a Parliamentary group) from the UK, four visits by high-level representatives from the US, three from China, and eight from India.

The purpose of the visits between Maldivian and Sri Lankan delegates varied from paying neighbourly courtesies, such as a Special Envoy of the President of the Maldives presenting financial assistance to Sri Lanka in the aftermath of floods in 2017, and the President of Sri Lanka visiting the Maldives for the Golden Jubilee of its Independence.7 Visits between the foreign ministers focused on economic and security issues, reiterating a need for increasing cooperation on improving tourism investments, education linkages and fishing issues.

While these are the right areas to focus on, what is notable is the lack of tangible results, such as more agreements or papers and studies that quantify progress in the relationship and track changing socio-economic needs and quagmires in both countries in order to tailor policy more effectively.

Figure 1

Source: Compiled from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Maldives.

Sri Lanka and the Maldives could also deepen the diplomatic relationship by exploring the Scandinavian approach8 of sharing embassies, or a model similar to that of the EU,9 where Maldivian citizens could contact the Sri Lankan embassies for consular services in countries that the Maldives does not have embassies. As shown in Figure 1, Sri Lanka’s stretch of diplomatic representation is far more expansive than the Maldives. There are no countries that the Maldives has embassies that Sri Lanka does not. However, there would be little incentive for the Maldives to expand its collection of embassies, since it has embassies in countries of strategic interest to it—the countries Maldivians visit the most, its top import and export partners (with the exception of France), and the mandatory missions in Geneva and New York for the purpose of being in the United Nations.

A system of embassy sharing would allow both nations to save on a portion of the cost of operating embassies. This might prove especially prudent in a time that both countries face the possibility of austerity measures to pay off foreign loan debts, and could also develop the diplomatic cooperation and trust between the two countries. Deepening diplomatic relations would also be especially advantageous when addressing regional powers and security issues facing both Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

The Maldives-Sri Lanka relationship should also be considered in the context of great power competition in the Indian Ocean. China’s BRI investments in the Indian Ocean region have been causing some consternation in India, which sees these projects as allowing China to gain a strategic foothold in the region and ‘encircle’ India.

Like in Sri Lanka, China has also invested in the Maldives. In December 2017, the Maldives signed a Free Trade Agreement with China10 and a Memorandum of Understanding which draws the Maldives into the BRI.11 China built the Sinamale Bridge, which links the capital city Malé with Hulhumalé—the island with Malé International Airport. Hulhumalé is being developed as a suburb to Malé and China also has construction contracts to build housing on this island.

While the exact figure owed to China by the Maldives is unclear, the construction of the sea bridge, the airport expansion and the construction buildings on Hulhmalé is estimated to be USD 600 million, while other reports have produced a figure of USD 1.5 billion.12 This raises similar questions in the Maldives that have been raised in Sri Lanka—how is this debt to be serviced, what value do these Chinese investments add to the country, and what employment is available to Maldivians on these projects?

If the debt needs to be restructured, Sri Lanka and the Maldives, along with other BRI countries, should coordinate policies to boost bargaining power in negotiations. Such a coordinated effort should insist that BRI-related construction projects be in partnership with local companies, which would necessitate passing on of technical know-how to the local companies, as well as a share of the profits. Such negotiations could also elucidate the acceptable quality standards for construction and infrastructure projects. Both countries should also increase transparency in their engagements with the BRI and other Chinese investments, and conduct feasibility studies and repayment plan reports, which should be readily accessible to the public to ensure public debate and consent.

Regarding India, both Sri Lanka and the Maldives has taken steps to reassure their regional neighbour that its strategic concerns would not be ignored. Sri Lanka has been very clear that the Hambantota port would not be used by China as a naval base, and has moved its Southern naval command to Hambantota to further underscore this commitment. Meanwhile, the Maldives’ newly-elected president is seen as pro-Indian, and was sworn into office with the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, in attendance.13

Both the Maldives and Sri Lanka have a dire need for foreign investment and aid, but since the scale and delivery of India’s foreign aid progress is reputed to be less than China’s, the two countries’ need to engage with China. A way to soothe India’s concerns about Chinese influence in the region is to underscore China’s role as an economic partner while highlighting India as both an economic partner and a security guarantor in the region.

An efficient system of communication, coordinated responses and policy between the littoral Indian Ocean States is vital to the security of the Indian Ocean region— both in terms of providing safe passage for cargo on the maritime routes, as well as enforcing law and order.

India is a vital player in Indian Ocean security as it has the biggest military in the region. Sri Lanka and the Maldives have leaned on India for assistance in various security matters. India has interceded in Sri Lanka during the war, and has stopped an attempted invasion of the Maldives in 1980. Both Sri Lanka and the Maldives have also received technical support from India. India has interceded in Sri Lanka during the war, and stopped an attempted invasion of the Maldives in 1980, an incident which brought India and the Maldives closer together while giving India international clout as a security guarantor in the region with President Reagan stating that it was “a valuable contribution to regional stability.”14 Both Sri Lanka and the Maldives have also received technical support from India. India has provided vessels to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, and installed radar along the coastline of the Maldives to increase its surveillance capabilities.15

The Maldives is the weakest of the triad on security capabilities. It does not have a navy, and uses its coastguards to patrol the waters. However, the fleet has only three offshore patrol vessels, three inshore vessels, seven auxiliary vessels, and 20 interceptor class harbour vessels,16 which needs to patrol an archipelago of 1200 islands, out of which only 200 islands are inhabited. In an attempt to overcome this shortcoming, the Maldives incorporated the security apparatus into the fishing fleet,17 which allows fishermen to report suspicious activity.

However, in the future, the Maldives should invest in drone technology to increase surveillance of uninhabited areas, with the appropriate legislature to clarify that the drones are to be used to surveil the seas and uninhabited islands so that privacy rights of citizens are protected. When the budget permits, the Maldives should also seek to improve its fleet of boats, perhaps buying at concessionary rate from another navy.

India’s coastguards also lead joint exercises with the coastguards of its two neighbours, like the DOSTI training which the three nations’ coastguards completed in November 2018.18 Such trainings should become more routine.

Another way to increase the security of the region, would be to move ahead with the Trilateral Maritime Security Cooperation Agreement that is in the works. According to the preliminary discussions this agreement would increase cooperation in Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), engage in training and capacity building, search and rescue (SAR), and oil pollution response.19 Currently, talks have stalled for various reasons. Seychelles and Mauritius are also interested in signing the agreement, which would make the region even more secure.

Until a multilateral deal is worked out, the Maldives and Sri Lanka could consider signing a bilateral agreement similar to Sri Lanka’s MOU20 with India signed in May 2018, which increases information sharing of ships and persons suspected of criminal activity, and builds a system of communication between Sri Lanka’s and India’s coastguards to counter piracy, smuggling drugs and arms and people trafficking. What is notably missing from this agenda is addressing environmental issues such as dumping of toxins and pollutants and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The Maldives and Sri Lanka, both have a valuable tourism industry based around beaches and should push to incorporate this aspect into the agenda, bearing in mind the long term environmental impacts on the Indian Ocean economies if sustainable use of the oceans is neglected.

The short travel distance between the Maldives and Sri Lanka (an hour and five minutes by plane) facilitates trade of goods and services, and there is a long history of economic relations between the two countries. In the modern trade relationship, however, there are several comparative advantages that the two nations can explore.

Trade in Goods

The Maldives, being an archipelago with a total land mass of 298 square kilometers compared to Sri Lanka’s 64,630 sq km, is heavily constrained by a lack of land and its small domestic market of just 392,473 people.21 This limits its ability to farm, extract natural resources without great environmental cost, and develop an industrial sector. Thus, it is heavily dependent on imports for almost all its goods.

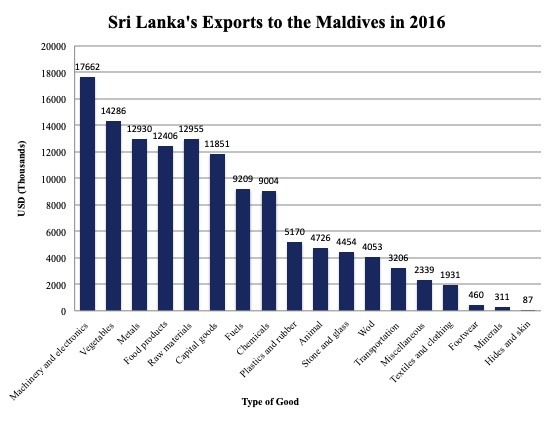

In 2016, Sri Lanka had a trade surplus of USD 16 million22 with the Maldives, making it the 23rd largest market for Sri Lanka’s exports. The goods exported23 to the Maldives are predominantly machinery and electronics, vegetables, metals, and food products. Figure 1, breaks down Sri Lanka’s exports to the Maldives.

Figure 2

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (2016)

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution (2016)

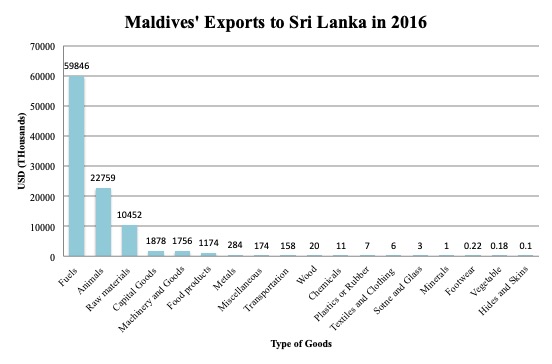

Despite the trade deficit, this relationship is also important to the Maldives as Sri Lanka is the second largest market for Maldivian exports. The main export of the Maldives to Sri Lanka are fuels in the distillation of oils and mineral fuels, and animal products. The breakdown of the Maldives’ exports to Sri Lanka are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Source: World Integrated Trading Solution (2016)

Source: World Integrated Trading Solution (2016)

Service Industry

Constrained by its ability to develop a manufacturing sector, the Maldives relies on the service sector for its foreign currency earnings. This is linked to an abundance of beautiful, pristine islands and an open door policy towards FDI in the tourism sector, which have underpinned the development of high-end tourism. Tourism was exploited so successfully that the Maldives progressed from being a low-income country with a GDP per capita of USD 260 in 1980, same as Sri Lanka, to an upper-middle income country in 2017 with a GDP per capita of USD 10,000 in 2017.24 Sri Lanka’s GDP per capita in 2017 was USD 4000.25 In 2016, the median monthly Maldivian household’s income was reported to be USD 1265,26 compared to Sri Lanka’s USD 241.27 Having a neighbour with a relatively high household income creates opportunities for Sri Lanka not only to sell goods, which it does well, but also to sell services.

Neither Sri Lanka nor the Maldives is a significant source of tourists for the other, with Maldivian tourists making up 3% of Sri Lanka’s tourist arrivals,28 and Sri Lankans constituting only 1% of the Maldives’ tourist arrivals.29 However, a Maldivian tourist spends USD 257 per day in Sri Lanka, making them the third highest spending tourists after Singaporeans (average daily spending of USD 323) and Indians (average daily spending of USD 296).30

Due to the Maldives’ small population, there may not be possible to increase the numbers of Maldivian tourists, however, Sri Lanka could look at services in demand in the Maldives and increase spending done in Sri Lanka. Maldivians travel overseas31 predominantly to seek medical attention, for vacation, and for education and training.

In 2017, 65% of medical tourists from the Maldives went to India, spending an average of USD 687.32 Sri Lanka is the second most popular destination, but its market share is 26% and spending is also lower with Maldivians spending about USD 499 on average.33 Sri Lanka could examine India’s competitive advantage in the medical industry, and consider how it can invest in its health services to develop medical tourism.

Sri Lanka is the most popular destination for Maldivians with about 40% of Maldivian tourists vacationing in Sri Lanka, compared to the second most popular destination, Malaysia, at 20%.34 The competitiveness of the Sri Lankan Rupee is most likely the cause. At the time the survey was conducted, the exchange rate of the currency was about ten Sri Lankan rupees to a Maldivian rufiyaa35—almost twice more affordable than India, with the Indian Rupee trading four Rupees to a Maldivian Rufiyaa. India would be a competitor to Sri Lanka, in terms of the shopping and cultural experiences offered.

All the countries offer visa on arrival to Maldivians. India36 and Malaysia37 offer a longer time on arrival for Maldivians—a 90-day tourist visa on arrival compared to Sri Lanka’s 30 days, with an option to extend. The convenience of daily flights run by Emirates and Sri Lankan Airlines between Malé and Colombo could also be a reason for this high number.

Another service that Sri Lanka can focus on would be education. The Maldives have a fledgeling tertiary education program. In 2018, the Ministry of Education of the Maldives signed agreements with some universities in Malaysia, India, and one in Sri Lanka to provide scholarships to Maldivian students.38 Sri Lanka’s education providers have also trained Maldivians civil servants, for example the University of Colombo trained statisticians39 of the the National Bureau of Statistics and the Maldivian National University. More universities and high schools could seek similar agreements with the Maldivian government to boost income from international students to local educational institutions.

This would also strengthen Sri Lanka’s soft power with its neighbour and help develop more people-to-people links. The Maldives would also be able to meet the demand for its tertiary education and fill gaps in technical knowledge. Consequently, Maldivians and Sri Lanka can develop a better understanding of each other’s business culture, language and markets, which would also ease business relations between Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

Private-Sector Investments and Joint Ventures

Private investment between the two countries tends to focus on tourism. It is the cash cow industry in the Maldives and Sri Lankan businesses have sought to invest in this. In 2014, Brown Investments, Palm Garden Hotel and Eden Hotel acquired a resort, Bodufaru Beach Resort, for USD 1.5 million.41 Last year, the Board of Investment of Sri Lanka approved a USD 3 million project by Alpha Kiname Holdings Lanka (Pvt) to set up 13 Eco style luxury suites41 and 26 chalets on a 15.3-acre land in Matale.

Recently, there has also been several construction and development opportunities in the Maldives. Sri Lankan firm, Coral Properties, announced its plan to invest USD 77 million in a mixed development project in Hulhumalé.42

There have also been some joint ventures between Maldivian companies and Sri Lankan commercial companies. In 2016, a Maldivian company, the Champa Brothers, and the Commercial Bank of Ceylon PLC launched banking operations in the Maldives under the Commercial Bank of Maldives (CBM).43

Private investment from Sri Lanka to the Maldives is likely to continue along these trends. However, the Maldives is in dire need of diversifying its economy as well addressing social issues of unemployment and economic inequality. While the economic growth rate of the Maldives has been steady at around 6%44 for the past couple of years, and is projected to continue in 2019, the Maldives struggles with inequality – ranking 103 with a coefficient of 37.4 on the Income Gini Coefficient while Sri Lanka ranks 73 with a coefficient of 36.4.45 Therefore, it needs to explore other sectors to develop. One such area to invest in is the digital economy. The Maldives has a reasonable digital infrastructure46 for an economy of its size, and it could invest in developing its public e-services. The two submarine cables the Maldives currently has is in partnership with Sri Lankan telecommunications companies—one with Sri Lanka Telecom and the other is with Lanka Bell. Hence, further investing in this area would also benefit these Sri Lankan companies. For the Maldives, especially in some of the rural islands, developing e-services and increasing digital connectivity would greatly reduce the cost of accessing services and would improve the quality of life for citizens. Through prudent government-private investment in ICT (Information and Communications Technologies), the Maldives could develop an e-commerce and cyber security hub in the region, much like Estonia in the EU.

The Maldives-Sri Lanka relations are focused on the right areas—whether it is the topic of diplomatic talks, the areas of economic investment or security cooperation. However, the bilateral relationship can be significantly improved through formalising these efforts through agreements.

As the new government of the Maldives settles on its foreign policy initiatives, there should be more onus on producing treaties and agreements based on past talks and workshops between the two countries. For instance, a treaty on countering IUU fishing would be especially paramount. Legislation could also be introduced in the respective governments to ease business transactions between Maldivian and Sri Lankan companies.

Commissioning studies and papers on the Sri Lankan-Maldivian relationship, and on changing socio-economic conditions in both countries would be useful to mark progress in the relationship and provide an impetus in public debate and tailor policy priorities.

Diplomatic cooperation could also involve the prospects of sharing embassies or, an agreement by which Maldivians can seek help from Sri Lankan embassies in countries the the Maldives does not have a mission.

Furthermore, diplomatic dialogue between both countries should emphasise coordinating foreign policy regarding regional powers such as India and China, in order to extract the best terms possible from Chinese investments in the region through collective bargaining, as well as to formulate a policy to reassure India of its security interest concerns.

On security matters, the coastguards of the Maldives and Sri Lanka should sign an MoU to establish a system of communication and information sharing, that would allow more effective monitoring of the Indian Ocean for criminal activity. Ideally, such a security agreement would become a trilateral one, which includes India and eventually be extended into multilateral agreement with Seychelles, Mauritius and other Indian Ocean littoral states.

A key dimension to security issues is enforcing and strengthening the framework of international system of laws that the world built up since the Second World War. The Maldives and Sri Lanka should vocally support the international forums that enforce and support these principles.

Building on the long history of organic trade and commerce between the Maldives and Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka and the Maldives should focus on its comparative advantages— Sri Lanka should focus on exports to the Maldives, as well as policy to undercut India’s medical tourism. Sri Lanka’s education services should be offered in order to improve the Maldives’ human capital and skills. At the same time, business between private companies should be encouraged. The Maldives should implement policy to attract investment to diversify its economy.

Fences make poor neighbours in a globalised world, where wealth and security are enhanced through open relations. Sri Lanka should use the opportunity presented by new government in the Maldives, to strengthen its diplomatic, economic, and security ties with its neighbours. Through coordination of policy, both nations could work towards achieving their goals of greater prosperity and wellbeing for their citizens.

1Daily Ft. (2019). Maldives President notes importance of relationship with Sri Lanka. [online] Available at: http://www.ft.lk/news/Maldives-President-notes-importance-of-relationship-with-Sri-Lanka/56-670191 [Accessed 9 Jan. 2019].

2Embassy of Maldives. (2016). Embassy. [online] Available at: http://maldivesembassy.lk/embassy/embassy [Accessed 17 Jan. 2019].

3Nuclear Threat Initiative. (2019). South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) | Treaties & Regimes | NTI. [online] Available at: https://www.nti.org/learn/treaties-and-regimes/south-asian-association-regional-cooperation-saarc/ [Accessed 17 Jan. 2019].

4Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Maldives. (2017). Fosim Quarterly. [online] Available at: https://foreign.gov.mv/images/fosim/Fosim_Qtrly_v3.pdf [Accessed 17 Jan. 2019].

5Ibid.

6Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka. (2018). Visits | Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka. [online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/visits/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2018].

7Ibid.

8LA Times. (2018). In Berlin, Five Scandinavian Nations Share Embassy Space. [online] Los Angeles Times. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/1999/oct/16/news/mn-22894 [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

9The European Commission. (2018). Home Consular Protection. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/consularprotection/index.action_en [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

10China South China Morning Post. (2018). China and Maldives sign free trade, maritime deals. [online] Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2123389/china-and-maldives-sign-free-trade-maritime-deals [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

11Ramachandran, S. (2018). The Maldives’ New Government: Mission Impossible? [online] The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/10/the-maldives-new-government-mission-impossible/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2018].

12Miglani, S. and Junayd, M. (2018). After Building Spree, Just How Much Does the Maldives Owe China? [online] Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-maldives-politics-china/after-building-spree-just-how-much-does-the-maldives-owe-china-idUSKCN1NS1J2[Accessed 18 Oct 2018].

13Times of India. (2018). PM Modi Arrives in Maldives to attend President Elect Solih’s Swearing-In ceremony. [online] Times of India. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/pm-modi-arrives-in-maldives-to-attend-president-elect-solihs-inauguration/articleshow/66667378.cms [Accessed 18 Oct 2018].

14Aryasinha, R. (1992). Indo-Maldives Relations and the Relevance of the Sri Lanka Factor. In: B. Bastiampillai, ed., India and her South Asian Neighbours. Colombo: Bandaranaike National Memorial Foundation, pp.91-116.

15DeSilva-Ranasinghe, S. and Sutton, M. (2015). Challenge for Maldivian Coastguard: Indian Ocean Security. Naval Institute. Available at: https://navalinstitute.com.au/challenge-for-maldivian-coast-guard-indian-ocean-security/ [Accessed 1 Dec 2018].

16Ibid.

17Ibid.

18Ministry of Defence. (2018).‘Surasha’ leaves for ‘DOSTI-XIV.’[online]. Ministry of Defence: Available http://www.defence.lk/new.asp?fname=Suraksha_leaves_for_DOSTI_XIV_20181125_01[Accessed 1 Dec 2018].

19Saberwal, A. (2016). Time to Revitalise and Expand the Trilateal Maritime Security Cooperation between India, Sri Lanka and Maldives. [online]. Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. Available at: https://idsa.in/idsacomments/trilateral-maritime-security-cooperation-india-sri-lanka-maldives_asaberwal_220316 [Accessed 1 Dec 2018].

20Memorandum of Understanding between the Coast Guard of the Republic of India and the Coast Guard of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka for the Establishment of a Collaborative Relationship to Combat Transnational Illegal Activities at Sea and Develop Regional Co-operation between the Indian Coast Guard and the Sri Lanka Coast Guard. (2019). [online] Ministry of External Affairs of the Government of India. Available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/LegalTreatiesDoc/LK18B3322.pdf [Accessed 9 Jan. 2019].

21CIA Worldfactbook. (2018). Maldives. [online] Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mv.html [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

22World Integrated Trade Solution. (2018). Sri Lanka Exports by Country and Region 2016. [online] Available at at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/LKA/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Export/Partner/all/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2018].

23Ibid

24The World Bank. (2018). GDP per capita. [online]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

25Ibid.

26Household Income and Expenditure Survey. (2016). National Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/nbs/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/HIES-Report-2016-Income-Updated.pdf [Accessed 1 Jan. 2019].

27Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs. (2019). [online] Available at: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/HIES/HIES2016/HIES2016_FinalReport.pdf [Accessed 9 Jan. 2019].

28Tourism Sector Comparison. (2018). [ebook] Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority. Available at: http://www.sltda.lk/sites/default/files/tourism-sector-comparative-analysis-2017.pdf#page=2 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2018].

29Flow of Tourists by Nationality. (2018). [ebook] Statistics Maldives. Available at: http://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/yearbook/2018/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/03/10.1.pdf#page=1 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2018].

30Tourism Sector Comparison. (2018). [ebook] Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority. Available at: http://www.sltda.lk/sites/default/files/tourism-sector-comparative-analysis-2017.pdf#page=2 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2018].

31Maldives Monetary Authority. (2017). Maldivians Travelling Abroad Survey 2017. [online]Available at:

http://www.mma.gov.mv/documents/Maldivians%20Travelling%20Abroad%20Survey/2017/MTA-Survey-2017.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan. 2019].

32Ibid.

33Oanda. (2019). Currency Converter | Foreign Exchange Rates | OANDA. [online] Available at: https://www.oanda.com/currency/converter/ [Accessed 8 Jan. 2019].

34Maldives Monetary Authority. (2017). Maldivians Travelling Abroad Survey 2017. [online]Available at:

http://www.mma.gov.mv/documents/Maldivians%20Travelling%20Abroad%20Survey/2017/MTA-Survey-2017.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan. 2019].

35Ibid.

36Bureau of Immigration. (2019). VISA Requirement. [online] Available at: https://boi.gov.in/content/visa-requirement [Accessed 8 Jan. 2019].

37Samir, A. (2019). Maldivian Citizens Visiting Malaysia Will Be Granted 90 Days Visa on Arrival – MFA. [online] Foreign.gov.mv. Available at: https://foreign.gov.mv/index.php/en/mediacentre/news/1963-maldivian-citizens-visiting-malaysia-will-be-granted-90-days-visa-on-arrival [Accessed 8 Jan. 2019].

38The Edition. (2018). Four universities offer higher education scholarships to Maldivian students. [online] Available at: https://edition.mv/news/4932 [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

39University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. (2018). University of Colombo to train statisticians of National Bureau of Statistics, Maldives and Maldivian National University under UNFPA funding. [online] Available at: https://cmb.ac.lk/index.php/university-of-colombo-to-train-statisticians-of-national-bureau-of-statistics-maldives-and-maldivian-national-university-under-unfpa-funding/ [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

40Daily FT. (2014). Brown Investments, Palm Garden Hotel and Eden Hotel in JV to acquire Maldives resort. [online] Available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/378711/Brown-Investments–Palm-Garden-Hotel-and-Eden-Hotel-in-JV-to-acquire-Maldives-resort- [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

41Daily Mirror. (2018). Maldivian company to invest US$ 3 mn in luxury chalets. [online] Available at: http://www.dailymirror.lk/76829/maldivian-company-to-invest-us-3-mn-in-luxury-chalets [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

42Daily News. (2018). Coral Properties Invests Rs. 9 bn in Sri Lanka and Maldives. [online] Available at: http://www.dailynews.lk/2018/08/20/business/160075/coral-properties-invests-rs-9-bn-sri-lanka-and-maldives [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

43Maldives Independent. (2018). Champa Brothers issued banking license. [online] Available at: https://maldivesindependent.com/business/champa-brothers-issued-banking-license-124272 [Accessed 6 Dec. 2018].

44Asian Development Bank. (2018). Maldives: Economy. [online] Available at: https://www.adb.org/countries/maldives/economy [Accessed 26 Dec. 2018].

45United Nations. (2018). Income Gini Coefficient. [online]. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/income-gini-coefficient[Accessed 26 Dec. 2018].

46Unescap. (2019). Broadband Infrastructure in South Asia and West Asia. [online] Available at: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Bhutan%20Presentation.pdf [Accessed 1 Jan. 2019].

*Farah Ibrahim is a Communications Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated. This Policy Brief was originally published on the Daily Ft.