April 3, 2020 Reading Time: 20 minutes

Reading Time: 20 min read

Image Credits: Maria Stewart / Unsplash

Adam Collins and Malinda Meegoda*

With a population of over 650 million in 2019, the Latin American and the Caribbean region (LAC) is a diverse and dynamic grouping of countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of over USD five trillion. Sri Lanka’s diplomatic engagement in the Latin American and Caribbean region stretch back to the 1950’s and has many strengths. However, there are several areas where Sri Lanka could improve existing economic and diplomatic linkages.

This Policy Brief will look at ways Sri Lanka can develop and expand its economic links with countries in the Latin American regions.

As Sri Lanka continues to find new pathways to integrate itself into the global economy, it needs to look beyond its traditional economic networks, partnerships, and alliances. One part of the world that is attracting greater attention is Latin America. While Sri Lanka’s diplomatic engagements in the region stretches back to the 1950s and have resulted in a significant amount of cultural and political engagement, the economic dimension has not kept pace with other aspects of diplomatic ties.

Despite all its internal economic and political challenges, LAC represents a combined GDP of USD 5.3 trillion (more than twice that of India’s), and 6% of global trade, including imports worth US$1.1 trillion in 2018. Therefore, the bilateral economic and political potential of LAC is something Sri Lankan policymakers and commercial actors should not underestimate. (See Box A.)

This Policy Brief will discuss Sri Lanka’s existing relationships with the LAC region, as well as the opportunities and challenges to strengthening this relationship. It also offers some policy suggestions on revitalising Sri Lanka relations with the region.

Table 1: Key Indicators for the LAC Region

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2019 Database

The LAC region consists of 33 countries spread across three distinct sub-regions; South America, Central America, and the Caribbean. (See Table 1.) The region has a combined population of over 590 million, with around two-thirds of this concentrated in South America. Similarly, more than two-thirds of the region’s economic output is produced in this sub-region. In addition, per capita income levels vary significantly across the LAC. The region is home to several smaller high-income countries, including Chile and Uruguay, as well as number of large middle-income countries, such as Brazil, and one low income country, Haiti.1

The historical trajectory of nearly all Latin American countries can be linked to policies emanating from the US and its interests in the region. Ever since the proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 and the exit of European powers, the US has been the most influential power in the region.2 The US presence in the region gave birth to number of international institutions and treaties to manage interstate relations, security concerns, and financial development.3 The prominent ones are the Organization of American States (OAS), Rio Treaty of 1947, and Inter-American Development Bank in 1959. Out of the 48 countries that own the Inter-American Development Bank, the US continues to control 30% of the voting share, dominating the ownership structure, with the closest second (11.2 % each) in the hands of Argentina and Brazil.4 However, since the 1990s Latin American countries have increasingly pursuing more independent paths on economic, political and economic security matters.

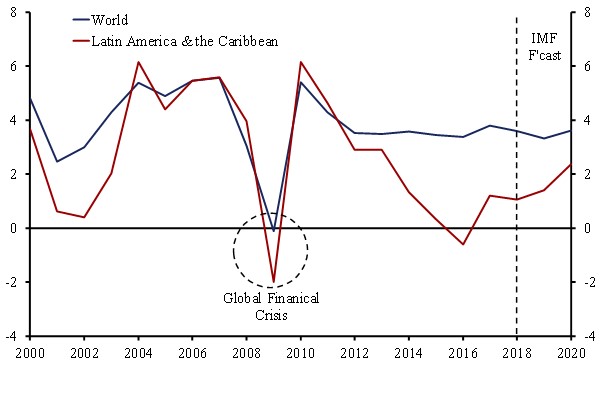

From the early 2000s, the LAC region enjoyed strong economic growth as the world economy boomed, partially thanks to the integration of the Chinese economy. China’s rapid growth during this period was accompanied with a voracious growth in its appetite for primary commodities, such as iron and copper, which Latin America has in abundance. This increased demand and prices and helping to provide Latin America’s major economies with a significant boost. However, as the Chinese economy began to slow in the years after the 2009 Global Financial Crisis, its appetite for LAC’s primary commodities diminished and global prices fell sharply. This created a substantial negative term of trade shocks, which caused economic growth to slow sharply between 2010 and 2016, which was worsened by economic crises in Venezuela and Argentina.5 Regional GDP growth has since picked up and the IMF expects it rise above 2% by 2020, though this would still be slower than the world as a whole.6 (See Figure 1.)

A handicap for many of the Latin American countries’ economies, (apart from the big three – Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico) is the absence of advanced industrialisation and economic diversification. Chile and Peru, two countries with the highest growth rates in the region in the past decade, are still highly dependent on the export of primary non-renewable commodities such as copper, silver and other metals.7 In addition, Latin American economies, much like the ones in South Asia, possess some of the lowest integration levels found in any regional grouping of countries.8 There have been many failed attempts at increasing economic cooperation by forming numerous regional organisations. These include UNASUR (Union of South American Nations), ALADI (Latin American Integration Association), SICA (The Central American Integration System), MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market), and many more. MERCOSUR, which was initiated by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, has failed to live up to its original expectations to open intra-regional trade. Trade among MERCOSUR countries, in fact, has declined from 19.5% in 1995 to 12.8 % in 2016.9

Figure 1: World and LAC Real GDP Growth (% y/y)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2019 Database

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2019 Database

Sri Lanka began establishing diplomatic links with LAC in the 1950s and currently has formal diplomatic relations with 30 countries in the region. The remaining three countries that Sri Lanka does not have formal diplomatic ties with are Belize, Antigua and Barbuda, and Saint Kitts and Nevis.

However, Sri Lanka has only two permanent missions in the region, located in Brazil and Cuba. (See Figure 2.) Brazil and Cuba have also established embassies in Sri Lanka. In addition to the two permanent missions, Sri Lanka has appointed twelve Honorary Consuls in LAC. Sri Lanka also engages with the region through various multilateral fora, including a Permanent mission to the United Nations in New York and the Commonwealth of Nations.10

Figure 2: Sri Lanka Diplomatic Presence in LAC

Source: Ministry of Foreign Relations of Sri Lanka

3.1 Cuba and Sri Lanka

Arguably, Sri Lanka’s closest ally historically in the Latin American region has been Cuba. Sri Lanka was the first Asian country to establish diplomatic ties with Cuba after the Castro-led the revolution in 1959.11 Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, one of the central architects of the Cuban revolution visited Sri Lanka in 1959 as the Minister of Industries to discuss the sugar trade. Sri Lanka was also a beneficiary of Cuba’s much lauded medical internationalism programme, responsible for sending thousands of medical professionals to all parts of the globe, as well as training doctors from the developing world in Cuba.12 While many other Latin American countries waxed and waned over their commitments to third-world solidarity movements such as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), Cuba steadfastly remained committed to the principles and objectives behind NAM.13 The institutional and people-to-people links between Sri Lanka and Cuba continue to grow as the two countries celebrated 60 years of diplomatic relations in 2019.

Most recently the Former State Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka, Vasantha Senanayake during an official visit to Havana, signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) and the Raul Roa Garcia Institute of International Relations, to advance scholastic research cooperation.14 Additionally, the former State Minister conducted a roundtable discussion with the Havana Chamber of Commerce where he remarked on the importance of identifying the Cuban market’s potential for Sri Lankan products.15 Sri Lanka is also scheduled to participate at the upcoming FIHAV Trade Fair in November 2019, which is the largest multisectoral trade fair in Cuba.16

3.2 Brazil and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka opened its first permanent mission in Brazil during the 1960s, but this was later closed in 1970. With the relocation of Brazil’s capital city from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília, Sri Lanka re-opened a permanent mission in 2002.17 While the total exports from Sri Lanka to Brazil are still small, the figure has grown steadily from USD 2.8 million in 2002 to USD 58 million in 2018.18 Sri Lanka’s trade relationship with Brazil has not been without its challenges. For a start, Portuguese, not Spanish, is the main language of Brazil, and Sri Lanka lacks these necessary language skills which hinder its entrance into this market. There is also some past tension in the trading relationship between the two countries. Sri Lanka’s only role as a complainant within the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) dispute settlement system was when Sri Lanka challenged Brazil’s decision to impose countervailing duties on Sri Lanka’s processed coconut products such as desiccated coconut, and coconut milk powder in 1996.

4.1 Trade and Investment

While it has grown significantly in recent years, Sri Lanka’s trade with LAC is limited. Bilateral trade in goods amounted to USD 561 million in 2019, which was just 1.7% of Sri Lanka’s total goods trade. As a comparison, Sri Lanka’s trade with the United States alone amounted to USD 3,734 million. This said, Sri Lanka maintains a modest trade surplus with the LAC region. Exports to the region amounted to USD 418 million in 2018 (3.6% of Sri Lanka’s total exports), compared to imports of USD 142 million (0.6% of Sri Lanka’s total imports). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Sri Lanka’s Trade with LAC

Source: UNCOMTRADE and IMF Direction of Trade Statistics

*2018 data are estimates based on partial data from IMF DOTS.

This bilateral trade surplus is dominated by a small number of countries. In particular, Sri Lanka posted a USD 165 million trade surplus with Mexico in 2018, as well as a USD 38 million surplus with Chile and a USD 35 million surplus with Peru. It is notable that these are not countries where Sri Lanka has permanent missions, though there are honorary consuls in Mexico and Peru. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Sri Lanka’s Good Trade Balance with Major LAC Markets (US Millions, 2018)

Source: UNCOMTRADE and IMF Direction of Trade Statistics

Sri Lanka’s exports to LAC are dominated by cinnamon, apparel and rubber products, which account for approximately 75% of all of Sri Lanka’s exports to the region. Cinnamon exports to LAC have grown particularly rapidly in recent years. (See Figure 5.) This reflects Sri Lanka’s comparative advantage in these items. Sri Lanka’s imports from the region, on the other hand, are dominated by iron, sugar and tobacco products, which reflects the dominance of primary commodities in the LAC region’s economic structure.

Figure 5: Sri Lanka’s Good Exports to Major LAC Countries

Source: UNCOMTRADE

1HS Code 0906; 2HS Codes 61,62, and 63; 3HS Code 40; 4Includes tea (Chile) and electrical goods (Mexico).

Bilateral investment flows between Sri Lanka and LAC also appear to be small. Sri Lanka received approximately US$68 million of foreign direct investment (FDI) from the LAC region between 2015 and 2018. This was just 1.2% of total inward FDI Sri Lanka received during this period (US$ 5.8 billion). A limited breakdown of source markets reveal that these investments are mainly from small Caribbean islands, such as the British Virgin Islands. Given the reputation of some Caribbean islands as centres for money laundering and tax evasion, Sri Lanka should be mindful of the potential risks associated with these financial flows. To increase and broaden the sources of FDI from LAC, Sri Lanka should consider leveraging the upcoming agreement with India (ECTA). This would allow potential investors to use Sri Lanka as a preferential entry point into the Indian market, while also benefitting from Sri Lanka a more favourable business environment and higher quality of life.

A number of large Sri Lankan firms have invested in LAC in recent years, particularly in the apparel, though comprehensive data is not available. MAS has established four manufacturing facilities across Mexico and Honduras, while Brandix has a plant Haiti.19 This is likely to be driven by the significant tariff preferences that these countries have when exporting to the US market and their geographical proximity to the US, which allows faster delivery times. It is notable that these countries do not have a permanent Sri Lankan diplomatic presence.

4.2 Tourism and Overseas Sri Lankans

The LAC region has not been a major source of tourists for Sri Lanka either. The country received roughly 8,134 tourists from this region, which is equivalent to just 0.3% of total tourist arrivals to Sri Lanka in 2018. At a country level, Brazil, Argentina and Chile were the largest markets, accounting for 69% of Sri Lanka’s tourists from the region in 2018. These figures are quite low compared to neighbouring countries. India received over 92,000 tourists from LAC in 2017 (0.9% of total tourist arrivals to India), while Maldives hosted more than 16,000 tourists from LAC in 2018 (1.1% of total tourist arrivals to the Maldives).

One of the reasons for limited tourists from LAC visiting Sri Lanka is poor air connectivity. Flight times and connections are not very appealing and may discourage individuals from travelling. However, given that India and the Maldives, which also have limited air connectivity with LAC, receive many more tourists from the region suggests there is also a lack of awareness of Sri Lanka’s tourism product. This could be addressed with greater marketing efforts in Spanish and Portuguese, and targeting key markets with significant outbound tourist flows, notably Brazil, Argentina and Chile.

A small number of Sri Lankans are also known to be working in the LAC region. They are mostly employed in hospitality, finance and the apparel sector in the Caribbean region. This may reflect the more common use of English in this sub-region and the presence of some Sri Lankan companies as noted above. While there may be scope to increase the number of Sri Lankans working in the Caribbean region based on the existing presence, the need for strong Spanish or Portuguese skills elsewhere in the LAC region is a significant barrier to greater employment opportunities for Sri Lankans in this part of the world. Given the large geographical distance from Sri Lanka, the LAC region is also not well known as potential destination for foreign employment.

The above analysis suggests that Sri Lanka’s ties with Latin America, while growing, are underexploited. This presents opportunities to increase engagement, though there are also significant challenges. One way to assess this is a SWOT analysis, which compiles the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of particular issues. This is a useful tool for assessing Sri Lanka’s bilateral relationship with a given country or region. Figure 6 shows preliminary SWOT analysis of Sri Lanka-LAC ties.

Figure 6: SWOT Analysis of Sri Lanka-LAC Ties

Source: Compiled by LKI

5.1 Strengths & Opportunities

The strengths in Sri Lanka’s bilateral relations with LAC lie in its strong and established political ties Cuba and increasing ties with Brazil, bolstered by its permanent missions in these locations. This is complemented by some limited success in building economic ties with the region. Trade flows, while small, have grown significantly in the past decade and Sri Lanka has become the world’s leading exporter of cinnamon to Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Peru. What’s more Sri Lanka’s maintains a modest goods trade surplus with the region. The presence of some large Sri Lankan firms in LAC, notably in the apparel sector, is also a notable strength that can be built upon. It demonstrates the ability of Sri Lankan firms to becomes world leaders and major outward investors.

The key opportunity for Sri Lanka in LAC is to build on these burgeoning economic ties to take the bilateral relationship to a more significant level. The possibility of growing Sri Lanka’s market share in its traditional products in LAC, such as tea, spices, and apparel, has not yet been fully exploited. This is particularly true in markets where Sri Lanka has permanent missions. For example, despite being the region’s largest market, Sri Lanka does not export any cinnamon to Brazil. The country is instead almost entirely supplied by Indonesia. In addition, there are a few potential avenues for Sri Lanka to expand its economic relations with Cuba in the agricultural, and pharmaceutical sectors. Cuba has expressed its interest in growing its coconut production as a potential export commodity, and Havana is keen on gaining expertise and research knowledge from Sri Lanka to develop this sector.20 At the same time Sri Lanka could seek technical cooperation from Cuba to uplift the standards and capacity of its domestic pharmaceutical industry.

Cuba’s biopharmaceutical industry, despite possessing fewer resources than other countries, currently sells medicine to over 50 countries, and holds over 1,200 international patents.21 What’s more, LAC’s sizeable middle class presents an opportunity to build a market for new and higher-value exports across the region. This could include some of the sectors highlighted in the National Export Strategy, including electrical equipment, ICT, processed food and beverages, boat building and wellness tourism.

Stronger bilateral engagement with various countries could also be supported through increased interaction with the various regional organisation in LAC. One important candidate may be the Pacific Alliance. After the MERCOSUR (Southern Common Market) project failed to live up to its lofty ambitions, four Latin American countries (Chile, Columbia, Mexico and Peru) that border the Pacific Ocean launched the Pacific Alliance initiative in 2011.22 The goal of the alliance was to form an area of integration to ensure complete freedom in the movement of goods, services, capital, and people. The commitment of four member states to the principles of free trade and open markets arguably gives the Pacific Alliance greater credibility over other region groupings and presents better opportunities for extra-regional partners.

The Pacific Alliance countries already account for 55% of Latin American exports, and this combined with a 240 million consumer market represents the eighth largest economy in the world.23 The sincerity of the alliance’s ambitions can be clearly seen in the number of policy choices it has made since its formation, which include the removal of 92% of customs tariffs in the past six years, and the formation of the Mercado Integrado Latinoamericano (MILA), an initiative to integrate the stock markets of the four countries.24 Pacific Alliance countries have also been actively pursuing greater economic engagement with Asia. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Singapore are associate members of the Pacific Alliance, while six Asian states (China, India, South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, and Japan) are Observers. In addition, Chile has six bilateral FTAs with Asian countries, while Peru has six, and Colombia and Mexico both have one. In contrast, Brazil has no FTAs with Asian countries. Mexico, Chile and Peru are also members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP). (See Table 2.)

No formal barriers exist for states to receive observer status within the Pacific Alliance. Sri Lanka or any other state that wishes to become an observer state could make a formal request to the President pro tempore. If the integration of members between the Pacific Alliance, CPTPP, and the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) come into fruition, an unparalleled number of free trade linkages, that smaller countries like Sri Lanka could potentially benefit from, will be formed.

Table 2: FTAs in force between Pacific Alliance Countries and Asian Countries

Source: The Organization of American State’s Foreign Trade Information System, Accessed 4 September 2019

Available at: www.sice.oas.org

5.2 Weaknesses & Threats

To make the most of this potential opportunity, the major weaknesses in the bilateral relationship must be addressed. These includes the limited knowledge Sri Lankan businesses have of the LAC region, compounded by the lack of significant Portuguese and Spanish skills in the local labour market, geographical distance and poor air connectivity. What’s more, the lack of any free trade agreement (FTAs) or bilateral investment treaties gives little incentive for stronger bilateral economic ties. Sri Lankan firms receive no preferences when accessing the LAC markets or vice versa. More fundamentally, limited diversification in Sri Lanka’s economic and export base is an obstacle to greater economic engagement. The presence of just two permanent missions to cover 33 independent states across a large geographical area is also a significant constraint to Sri Lanka’s diplomatic engagement with the region.

Adding to this, Sri Lanka must be mindful of the external threats to stronger relations with LAC. The biggest is that many of the largest economies in the region, such as Brazil, are relatively protected and have limited interest in liberalisation. The economic performance of LAC economies has also been mixed in recent years. The gradual slowdown in the Chinese economy has had a major knock impact on South America in particular, as it is a major market for the region’s commodity exports. What’s more, some economies in the region have also experienced serious economic and political crisis in recent years (e.g. Venezuela and Argentina). Attempts to increase Sri Lanka’s economic and political engagement with LAC could also be overshadowed by the similar actions of much larger Asian economies, including India and China, and it should be mindful of the broader geopolitical rivalries playing out in the region.

Sri Lanka’s limited economic ties with the LAC region partly reflect its geographical distance from the region, the language barriers, and limited diversification in Sri Lanka’s economic base. These factors are difficult to change. Nonetheless, even bearing these issues in mind, Sri Lanka’s economic links with LAC are underexploited and, as such, can be improved. This will take time and should ideally be business-led, but the government also has an important role in providing support.

6.1 Upgrading current diplomatic relationships with Brazil and Cuba

It is important to maximise the diplomatic and economic linkages in countries where Sri Lanka has already established permanent missions such as Cuba and Brazil. Sri Lanka’s missions in these two markets have over the years conducted and participated in numerous economic promotion activities, and these activities need to be expanded further. Sri Lanka could also propose several cultural promotion and exchange programs between Brazil and Sri Lanka, to show its intent as a partner worth investing in South Asia. Sri Lanka could also look at ways to attract foreign direct investment from Brazilian companies particularly through joint partnerships with local firms to increase the productivity and volume of the manufacturing sector in Sri Lanka. Brazil’s considerable prowess in science and technology is evident in the presence of a fairly successful aerospace industry – a sector only a handful of countries have succeeded on a global scale.25

6.2 Expanding diplomatic links in Latin America

Sri Lanka should look to establish a diplomatic mission either in Chile or Mexico. However, Sri Lanka should also make sure that the mission has access to resource persons who are familiar with the unique business environment in Latin America and possess full professional proficiency in the Spanish language. Without these two elements, this will be a fruitless exercise that will only incur additional expenses to the Sri Lankan taxpayer. In this regard, Singapore, despite being one of the richest states in Asia maintains only one permanent diplomatic mission in Latin America (Brazil).26 Sri Lanka needs to adopt a more rigorous evaluation framework based on economic grounds when opening permanent missions abroad in the future. One possibility would be to expand the mandate of the Sri Lankan embassy in Brazil to become a regional headquarters for Sri Lanka’s engagement with Latin America, while the embassy in Cuba could act in a similar way for the Caribbean region.

Sri Lanka should also consider boosting interaction with LAC countries at multilateral fora, such as the United Nations, Organisation and American States and Inter-American Development Bank. Engagement with the various regional organisations in LAC could also be increased. For example, Sri Lanka could seek to gain observer status to the Pacific Alliance.

6.3 Increase cultural ties and develop language capacity

As the lack of Spanish language speakers remains a hindrance to developing more robust bilateral ties between Sri Lanka and Latin American countries. Sri Lanka could lobby the Spanish government to establish a Cervantes Institute in Sri Lanka. In addition to increasing the number of Spanish speakers, it would open up more opportunities for Sri Lankan students to seek training and other post-secondary educational credentials in both Spain and Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. There also needs to be a push to incentivise tourism from Latin American countries. This requires developing better air connectivity, and the promotion of Sri Lanka as a favourable destination through the existing missions based in Cuba and Brazil. Bilateral cooperation on promoting the Portuguese language, in addition to the Spanish language, could also be a part of Sri Lanka’s cultural diplomacy program in the LAC region.

6.4 Minimise non-tariff barriers and explore Free Trade Agreements with Pacific Alliance countries

If Sri Lanka intends to make inroads and form economic linkages with the Latin American market, there are a number of key policy decisions that it needs to make. It is important to look at areas where possible to minimise Sri Lanka’s non-tariff barriers to trade. Administrative delays, and other behind the border challenges are perhaps the areas that need to be prioritised. Sri Lanka is currently negotiating possible Free Trade Agreements with China, India and Thailand. Sri Lanka could additionally look to sign a bilateral free trade agreement with one of the Pacific Alliance countries, as Singapore has done with Chile, to generate a pathway to becoming an Associate Member. Sri Lanka also needs to develop its overall trade negotiation capacity. This could include improving Sri Lanka’s trade experts, and other relevant institutions.

As to which country Sri Lanka should partner with remains a more complicated question, as the four countries have their unique strengths and weaknesses. Chile, arguably remains the most suitable candidate for a number of important economic and governance reasons. Chile, remains the most outward-oriented out of the four Pacific Alliance countries in forming Preferential Trade Agreements, and Free Trade Agreements with Asian countries. Chile at present maintains 15 FTAs, and numerous Economic Cooperation Agreements. In addition, Chile represents a degree of political stability rarely found elsewhere in Latin America. The continuity of economic and trade policies across various administrations in Chile remains a positive incentive to potential investors. While corruption is endemic in majority of the Latin American countries, Chile has managed to maintain a higher degree of transparency and minimise corruption. Transparency International ranked Chile as the 28th least corrupt country in the world in 2018. This ranking is far higher in comparison to Argentina (85), Brazil (105), Columbia (99), Mexico (138), and Peru (105).27

Nevertheless, Chile does possess several structural weaknesses in its economy. The two main ones being; the relatively smaller size of the domestic market, and an over dependence on the mining industry (primarily, copper leaving it vulnerable to external shocks such as global price fluctuations.

Despite significant, political, cultural and diplomatic engagement with LAC, Sri Lanka’s economic engagement with the region has lagged. Trade and investment flows, while growing, are limited and focused on a small number of countries and sector.

Developing greater economic ties with the LAC also contain some inherent challenges. The two primary ones being the geographical distance between markets in Latin America and Asia, and the cultural and linguistic differences that can have an impact on commercial activities. Nevertheless, other Asian countries particularly large players such as South Korea, continue to look towards increasing their diplomatic and economic engagements in the LAC region.

At present, with Sri Lanka’s two permanent missions based in the LAC region, the total value of trade between the region and Sri Lanka shows positive growth rates, albeit somewhat modest compared to other traditional markets such as North America. In order to maximise the trade potential between the LAC region and Sri Lanka, a two-pronged strategy is required. This would entail strengthening and expanding existing diplomatic relationships where Sri Lanka already maintains permanent missions (Brazil and Cuba), as well as look towards expanding ties with other countries in a systematic manner. Sri Lanka should also explore the possibility of establishing Free Trade Agreements with countries in the LAC region. Finally, while the focus of this Brief has primarily been Latin American countries, Sri Lanka could look also look towards increasing its engagement with the Caribbean states.

1Santiago, J. (2013). Did you know…? Ten facts about Latin America. World Economic Forum. [Online] Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2013/04/did-you-know-ten-facts-about-latin-america/

[Accessed 2 September 2019].

2The Economist. (2019). What is the Monroe Doctrine?

[Online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2019/02/12/what-is-the-monroe-doctrine [Accessed 2 September 2019].

3Krepp, S. (2017). Cuba and the OAS: A Story of Dramatic Fallout and Reconciliation. Wilson Center. [Online] Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/cuba-and-the-oas-story-dramatic-fallout-and-reconciliation [Accessed 2 September 2019].

4Kay, C. (2002). Why East Asia overtook Latin America: Agrarian reform, Industrialisation and Development. Third World Quarterly. 2(3).

[Online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/44830493_Why_East_Asia_overtook_Latin_

America_Agrarian_reform_industrialisation_and_development [Accessed 3 September 2019].

5Mendez-Guerra, C. (2014). On the Development Gap between Latin America and East Asia: Welfare, Efficiency, and Misallocation. Forum of International Development Studies. Nagoya University. [Online] Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/62588/1/03.pdf#page=7

[Accessed 14 March 2019].

6World Bank Data (2018). GDP Per Capita. [Online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.pcap.cd [Accessed 15 March 2019].

7Johnson, T. (2010). Peru’s Mineral Wealth and Woes. Council on Foreign Relations. [Online] Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/perus-mineral-wealth-and-woes [Accessed 14 March 2019].

8Beaton, K. et al. (2017). Trade Integration in Latin America: A Network Perspective. International Monetary Fund. [Online] Available at: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WP/2017/wp17148.ashx

[Accessed 20 March 2019].

9Sistema Económico Latinoamericano y del Caribe (SELA). (2014). Assessment Report on Intra-Regional Trade in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1980-2013. [Online] Available at: http://www.sela.org/media/268490/assessment-report-on-intra-regional-trade-in-lac_-1980-2013.pdf#page=64 , Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2018). International Trade in Goods in Latin America and the Caribbean. [Online] Available at: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44342/1/Boletin_estadistico_32_en.pdf

[Accessed 3 March 2019].

10Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2017). Missions. [Online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/missions/sri-lanka-missions-overseas/america/brazil/ [Accessed 5 March 2019].

11Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2009). Commemorative ceremony celebrating 50 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Cuba and Sri Lanka. [Online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/commemorative-ceremony-celebrating-50-years-of-diplomatic-relations-between-cuba-and-sri-lanka-29th-july-2009/

[Accessed 23 March 2019].

12Hettiarachchi, K. (2016). Castro, JR and Lankan students. [Online] The Sunday Times. Available at: http://www.sundaytimes.lk/161204/sunday-times-2/castro-jr-and-lankan-students-218954.html

[Accessed 23 March 2019].

13Singham, A.W. and Van Dinh, T. eds. (1976). From Bandung to Colombo: Conferences of the Non-Aligned Countries 1955-75. Third Press Review of Books Company.

14Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka. (2019). Commemoration of 60 years of diplomatic ties between Sri Lanka and Cuba. [Online] Available at: https://www.mfa.gov.lk/sri-lanka-and-cuba-60-yrs_eng/

[Accessed 24 March 2019].

15Ibid.

16Market Development Division Sri Lanka Export Development Board. (2017). Market Strategies for Latin American Region. [Online] Available at: http://www.srilankabusiness.com/pdf/market_region_strategies/market-strategies-for-latin-america-2017-new.pdf [Accessed 19 March 2019].

17Ibid.

18Ibid.

19Masholdings (2019). MAS Acme. [Online] Available at:

http://www.masholdings.com/americas/index.html [Accessed 3 March 2019].

20Ramos Rodriguez, J. (2019). Interview with the Cuban Ambassador to Sri Lanka.

21O’Farrill, A. (2018). How Cuba Became a Biopharma Juggernaut. Institute for New Economic Thinking. [Online] Available at: https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/how-cuba-became-a-biopharma-juggernaut [Accessed 3 June 2019].

22Alianzapacifico. (2019). What is the Pacific Alliance? – Alianza del Pacífico. [Online] Available at: https://alianzapacifico.net/en/what-is-the-pacific-alliance/ [Accessed 3 March 2019].

23Ibid.

24Mercadomila.com. (2019). MILA | Mercado Integrado Latinoamericano. [Online] Available at: https://mercadomila.com/en/who-we-are/what-we-do/ [Accessed 3 March 2019].

25Utsumi, I. (2014). The Brazilian Aerospace Industry. The Brazil Business. [Online] Available at: https://thebrazilbusiness.com/article/brazilian-aerospace-industry [Accessed 2 September 2019].

26Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singapore. (2019). Overseas Missions. [Online] Available at:

https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Overseas-Missions [Accessed 18 March 2019].

27Transparency International (2019). Corruption Perceptions Index. [Online] Available at:

https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/cpi-2018-regional-analysis-americas [Accessed 15 May 2019].

*Adam Collins is a former Research Fellow at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). Malinda Meegoda is a Research Associate at LKI. The authors are grateful for the support and comments from officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They would also like to extend their thanks to the attendees of the stakeholder meeting, held on 12 September 2019 at LKI. The opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.