Freedom of Navigation

October 10, 2018 Reading Time: 13 minutes

Reading Time: 13 min read

Image Credit: dewald@dewaldkirsten/depositphotos

Myra Sivaloganathan∗

This LKI Explainer explores the legal concept of ‘Freedom of Navigation’ especially as articulated in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1983), the South China Sea Code of Conduct (2017), and the Jakarta Concord (2016). It considers ways in which Sri Lanka can implement and enforce freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean.

Contents

- What is Freedom of Navigation?

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- Objectives and Principles of UNCLOS

- Freedom of Navigation Programme

- Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea

- Freedom of Navigation in the Indian Ocean

- Sri Lanka and Freedom of Navigation

1. What is Freedom of Navigation?

- Freedom of navigation is a principle that allows all ships flying the flags of sovereign States to navigate and roam international waters freely, subject to restrictions in customary international law1 (including the sovereignty of States, territorial seas, and Exclusive Economic Zones), as well as under treaties.

- Vessels exercising the freedom of navigation are subject to the exclusive jurisdiction2 of the flag State. Flag States are the States under which a ship is registered or flagged. States have a responsibility over their ships, including when a ship is outside their territorial waters.3

- The principle was first articulated in a legal context in 1604 by Hugo Grotius of the Netherlands,4 who affirmed that since the sea is fluid, intangible, and cannot be possessed, the Portuguese could not claim exclusive possession of waters around the East Indies.

- The significance of the freedom of navigation, and its articulation by Hugo Grotius, is that it led to the triumph of his notion of Mare Liberum 5 (free sea) over John Seldon’s conception of Mare Clausum (closed sea). Grotius rejected the idea that national sovereignty could extend to the high seas.

- Thus, all States met on an equal footing on the high seas, and no State can independently impose its legislative will 6 upon use of the high seas.

2. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- The 1955 Report of the International Law Commission7 stated that any freedom exercised in the interest of all must also be regulated. The law of the sea, therefore, contains certain rules and regulations, designed not to limit the freedom of the high seas, but to safeguard its exercise in the interest of the international community.

- The first UN Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I) took place in Geneva in 1956. UNCLOS I resulted in four treaties, which were signed in 1958. The Convention on the High Seas was regarded as a codification of customary international law and therefore binding on all States.

- The four treaties of the 1958 Conference – including the Convention on the High Sea – were signed by Sri Lanka in 1958, but never ratified. The Conference left unresolved the maximum breadth of the territorial sea,8 the limits of the fishery jurisdiction of coastal States and the rights of foreign ships to pass through straits used for international navigation.

- The second UN Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS II) took place in 1960. This conference did not result in any new agreements; substantive decisions on the breadth of the territorial sea and fishery limits were deferred to a later time.

- The third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) (1973-1982) addressed all outstanding issues9 concerning the law of the sea. Legal and scientific experts from more than 150 States participated in formulating over 300 articles and seven Annexes.

- UNCLOS III set out the international norms governing the use of the world’s oceans10 and its resources by States (through international divisions of territorial sea, Exclusive Economic Zones, continental shelf and recognising the status of the deep seabed). It is one of the most widely accepted international conventions, with 167 current member States11 including Russia, China, and the EU.

- UNCLOS III replaces the two prior attempts to articulate the rights of States with respect to their territorial seas, continental shelves, use of the high seas, and management of maritime resources. The convention was signed by Sri Lanka in 1982 and ratified in 1994.12

3. Objectives and Principles of UNCLOS

- Freedom of navigation rights concern the types of operations permitted within specific maritime zones.

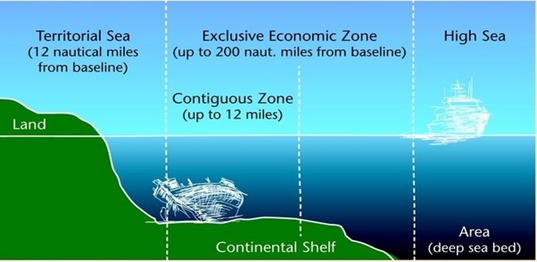

- The freedom of navigation is subject to the rights of coastal States in those maritime zones closest to the shore. UNCLOS distinguishes between seven maritime zones:13 internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone,14 the continental shelf, the Exclusive Economic Zone, the high seas and the deep seabed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Source: Garry Taylor (2015). The Law of the Sea and “creeping jurisdiction” of coastal States

- The territorial sea extends up to 12 nautical miles from land and is considered subject to the sovereignty of a coastal State.

- A State has the exclusive right to make, apply and execute its own laws in the territorial sea without foreign interference, subject to limitations under UNCLOS and other rules of international law.

- In particular, according to UNCLOS, all ships of all States enjoy the right of innocent passage15 through the territorial sea of other States. Innocent passage requires that vessels move directly and continuously through the territorial sea;16 military operations, fishing, pollution and surveillance operations are prohibited.

- States that have ratified UNCLOS are obligated to respect this provision and the right of innocent passage is also recognised as customary international law therefore also binding on States that are not party to UNCLOS.

- The contiguous zone extends another 12 nautical miles, ending up to 24 nautical miles from land. The contiguous zone is not subject to the sovereignty of the coastal State – it is considered part of international waters.

- Within the contiguous zone, coastal States may only exercise limited jurisdiction over foreign-flagged vessels to prevent and punish offences related to its fiscal, immigration, sanitary and customs laws. Any coastal State exercise of jurisdiction for security purposes more broadly is not permissible.

- Apart from these limited coastal State powers in the contiguous zone, vessels otherwise enjoy the freedom of navigation in this maritime area.

- The exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extends up to 200 nautical miles from land and includes both the territorial sea, and the contiguous zone. Within the 200 nautical miles, a coastal State has sovereign rights to the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. A coastal State also has exclusive jurisdiction over artificial islands and installations, for the protection and preservation of the marine environment and over marine scientific research.

- The exclusive economic zone is considered part of international waters;17 States do not have the right to limit navigation therein. Obligations of due regard are nonetheless applicable in the respective exercise of rights within the EEZ.

- The objectives of UNCLOS are to:

- Protect the economic, environmental, and national security concerns of coastal States;

- Strengthen coastal State rights up to 200 miles offshore;

- Protect the marine environment;

- Protect freedom of navigation; and

- Maintain international peace.

- Articles relevant to freedom of navigation include:

- Article 36: Freedom of navigation in straits used for international navigation

- Article 38: Freedom of transit passage in straits used for international navigation

- Article 58: Freedom of navigation in the exclusive economic zone

- Article 78: The exercise of the rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf must not infringe or result in any unjustifiable interference with navigation and other rights, and freedoms of other States

- Article 87: Freedom of the high seas, for both coastal and landlocked States, includes freedom of navigation, freedom of overflight, freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines, freedom to construct artificial islands, freedom of fishing, and freedom of scientific research

4. Freedom of Navigation Programme

- The United States (US) played an instrumental role in forming UNCLOS18 in the 1970s, despite not signing or ratifying the treaty

- Critics in the US have argued that:

- UNCLOS is flawed and would detract from US interests by ceding sovereignty19 to international organisations and tribunals.

- The US should not bind itself to international bureaucracies, such as the International Seabed Authority (ISA) created by UNCLOS. These bureaucracies are often hostile to US interests and the ISA, in particular, is threatening since there is no veto for the US.20

- Joining the Convention would expose the US to frivolous lawsuits for maritime activity. Critics assert that the treaty would become a weapon for environmental activists21 to bring legal claims against American companies and the US Navy.

- Nevertheless, the US recognises the importance of maintaining the freedom of navigation, and has, therefore, initiated its own Freedom of Navigation Operation22 (FONOP). The programme was created to ensure stability and consistency with international law.

- The programme was prompted by US concerns over the impact of excessive maritime claims on national security23 and international trade. The programme includes:

- Diplomatic communications, in the form of correspondence and formal protest notes;

- Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) by the US naval and air forces to assert internationally recognised navigational rights and freedoms; and

- Bilateral and multilateral consultations to encourage maritime stability and adherence to the provisions of UNCLOS.

- Over the past year and a half, the US has conducted eight FONOPs24 in the South China Sea.

- In 2015-2016, the US FONOPs challenged the illegal requirement of China, Taiwan, and Vietnam that ships provide advance notice before transiting through a State’s territorial sea under innocent passage.

- In 2017, the US also challenged claims from China, Vietnam, and Taiwan to Triton Island within the Paracel Island chain.

5. Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea

- The US has a specific freedom of navigation programme in the South China Sea. In light of China’s extensive maritime claims and assertions, the US conducts freedom of navigation operations to assert maritime rights in the South China Sea.25

- The South China Sea contains some of the world’s most important shipping lanes; it is estimated that USD 5.3 trillion in trade26 passes through the region annually.

- Freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is governed by UNCLOS, and the Code of Conduct on the South China Sea.

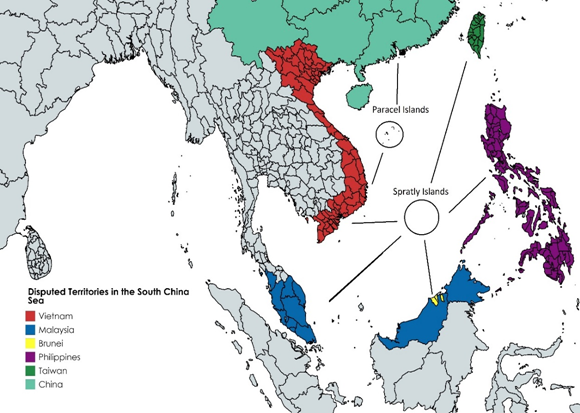

- The South China Sea is home to a number of longstanding territorial disputes and sovereignty claims between Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam (see Figure 2). Most territorial disputes focus on features within the Paracel and Spratly Island groups.

- To reinforce territorial claims, the States listed above occupy features of the South China Sea and have reclaimed land, built infrastructure, and stationed troops or military hardware. Such actions have raised concerns over the possibility of conflict.

- Excessive maritime claims27 are assertions by States that are: (1) inconsistent with the legal divisions of ocean and airspace of UNCLOS (e.g. territorial sea claims greater than 12 miles) or (2) restrictions on navigation, and overflight rights (e.g. required advanced notification of warships and naval auxiliaries).

Figure 2:

Source: South China Sea Verdict (2016). The Wall Street Journal.

- At the 8th ASEAN Summit in Phnom Penh (2002), China and ASEAN had agreed upon a Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea28 (DOC) which promised to “enhance favourable conditions for a peaceful and durable solution of differences29 and disputes among countries concerned.” The Declaration30 affirms:

- Respect for and commitment to freedom of navigation in and above the South China Sea;

- Pledge to resolve territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means; and

- China and ASEAN’s commitment to exercising self-restraint in activities which would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability.

- Many consider the DOC ineffective and intrinsically flawed, since it does not have the legal power to restrict claimants’ behavior31 in the South China Sea. Furthermore, the text of the DOC provides little information on the specific implementation of forms of cooperation in the South China Sea.

- In August 2017, ASEAN and China agreed to a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea32 (CoC). The CoC is intended to supersede the DOC, and contains a “set of norms to guide the conduct of parties and promote maritime cooperation in the South China Sea.”

- The CoC framework will “promote mutual trust,33 cooperation and confidence, prevent incidents, manage incidents should they occur and create a favourable environment for the peaceful resolution of disputes.”

- The CoC will also maintain “respect for each other’s independence,34 sovereignty and territorial integrity in accordance with international law, and the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other States.”

- The CoC is not, however, “an instrument to settle territorial disputes35 or maritime delimitation issues.”

- Critics maintain that a non-legally binding CoC would be “meaningless”36 and not differ substantially from the 2002 DOC.

6. Freedom of Navigation in the Indian Ocean

- The Indian Ocean rim region is host to 2.7 billion people,37 and the ocean itself carries two thirds38 of the world’s oil shipments.38 Freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean is governed by UNCLOS and the Jakarta Concord. Comoros, Somalia, UAE and Iran are among the Indian Ocean Rim States that have not ratified UNCLOS.

- The Jakarta Concord is an agreement to maintain peace and stable relations39 among member States of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). In March 2017, 21 member countries of IORA signed the Jakarta Concord, titled “Promoting Regional Cooperation for a Peaceful, Stable, and Prosperous Indian Ocean.”40

- In the Jakarta Concord, IORA member States declare their commitment to promoting maritime safety, enhancing trade and investment cooperation, promoting sustainable fisheries management and development, enhancing disaster risk management, and fostering tourism and cultural exchanges.

- In particular, Article 16a of the document affirms the freedoms of navigation and overflight41 in accordance with UNCLOS and international law, to promote maritime safety and security.

- To implement provisions of the Jakarta Concord, IORA States have also agreed on an Action Plan for 2017-2021.42 Long-term goals involve establishing a regional surveillance network with Member States, and deepening collaboration between regional governments and multilateral bodies.

7. Sri Lanka and Freedom of Navigation

- In 1971, at the 26th session of the UN General Assembly, Sri Lankan Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike submitted a proposal to declare the Indian Ocean a “Zone of Peace.” The resulting “Declaration of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace”43 was adopted by the General Assembly as Resolution 2832 (XXVII).44

- Sri Lanka is party to UNCLOS III, and ratified UNCLOS in 1994. Sri Lanka is also among the IORA member States who signed the Jakarta Concord.

- In 1974, a bilateral agreement45 between Sri Lanka and India established maritime boundaries46 between the Gulf of Mannar and the Bay of Bengal. Kachchativu Island, a strategically important island for fishing, which Sri Lanka and India both claimed in 1921, fell under Sri Lanka’s sovereignty.

- The bilateral agreement, which was realised through cooperative negotiation and calculations, is an example of Sri Lanka’s commitment to the drawing of clear maritime boundaries. This commitment in turn ensures adherence to international law, and the principle of freedom of navigation.

- In maritime security, Sri Lanka could become a central body that other nations consult,46 by hosting an institution that deals with a particular maritime security threat (such as bottom trawling and destructive fishing).47 For example, through ReCAAP – an organisation focused on piracy and armed robbery at sea – Singapore has become the centre for information sharing on this topic.

- Sri Lanka could also learn from law enforcement operations around transnational crime and apply such principles to the case of foreign vessels. The UNODC piracy prosecution model48 could provide inspiration in this regard.

- Similarly, Sri Lanka could create guidelines for nuclear conduct in the maritime domain, to ensure the prohibition of testing and use of nuclear weapons in the Indian Ocean, as stated in the 1971 Zone of Peace resolution.49

- Through convening Indian Ocean States and major users, Sri Lanka could help articulate key guidelines and promote freedom of navigation practices to ensure that disputes are minimised and excessive maritime claims are efficiently resolved.

8. Key Readings

Antrim et al (2007). Law of the Sea Briefing Book. University of Virginia. Accessed from: www.virginia.edu/colp/pdf/Law_of_the_Sea_Briefing_Book.pdf

Freund, E. (2017). Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea: A Practical Guide. Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Accessed from: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/freedom-navigation-south-china-sea-practical-guide

Houck, James W. and Nicole M. Anderson. (2014). The United States, China, and Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea. PennState Law. Accessed from: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1230&context=fac_works

Klein, N. (2011). Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea. New York. Oxford University Press.

Wolfrum, R. (2008). Freedom of Navigation: New Challenges. International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea. Accessed from: https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/statements_of_president/wolfrum/freedom_navigation_080108_eng.pdf

Notes

1International Tribunal for the Law. Freedom of Navigation: New Challenges.

2United Nations. (1958). Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 92. Accessed from: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

3United Nations. (1958). Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 6. Accessed from: http://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/8_1_1958_high_seas.pdf https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/statements_of_president/wolfrum/freedom_navigation_080108_eng.pdf#page=2

4Grotius, H. (2004). The Free Sea. Liberty Fund. Accessed from: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/armitage/files/free_sea_ebook.pdf#page=16

5Becker, Michael A. (2015) “The Shifting Public Order of Oceans: Freedom of Navigation and the Interdiction of Ships at Sea.” Harvard International Law Journal. 46(1). Accessed from: http://www.harvardilj.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/HILJ_46-1_Becker.pdf#page=39

6Ibid.

7UN International Law Commission. (1955). Report of the International Law Commission Covering the Work of its Seventh Session 2 May – 8 July 1955. United Nations. Accessed from: http://legal.un.org/ilc/documentation/english/reports/a_cn4_94.pdf#page=5.

8Pinto, M. C. W. (2007). The United Nations, Sri Lanka and the Law of the sea. The Island. Accessed from: http://www.island.lk/2007/05/13/features1.html

9Ibid.

10Houck, James W. and Nicole M. Anderson. (2014). The United States, China, and Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea. PennState Law. Accessed from: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1230&context=fac_works.

11United Nations. (1994). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: Entry into Force. Accessed from: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/MTDSG/Volume%20II/Chapter%20XXI/XXI-6.en.pdf

12Antrim et al (2007). Law of the Sea Briefing Book. University of Virginia. Accessed from: www.virginia.edu/colp/pdf/Law_of_the_Sea_Briefing_Book.pdf#page=74

13 Freund, E. (2017). Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea: A Practical Guide. Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Accessed from: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/freedom-navigation-south-china-sea-practical-guide

14 United Nations. (1958). Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. Articles 3-4, 24. Accessed from: http://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/8_1_1958_territorial_sea.pdf.

15 United Nations. (1982). Convention on the Law of the Sea. Article 21. Accessed from: http://www.un.org/dehttp://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/8_1_1958_territorial_sea.pdpts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf#page=24

16United Nations (1958). Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. Section III, Article 14. Accessed from: http://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/8_1_1958_territorial_sea.pdf#page=5

17 United Nations. (1982). Convention on the Law of the Sea. Articles 36, 45b, 78. Accessed from: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

18 Almond, Roncevert Ganan. U.S. Ratification of the Law o the Sea Convention. The Diplomat. Accessed from: https://thediplomat.com/2017/05/u-s-ratification-of-the-law-of-the-sea-convention/

19 Groves, S. (2011). Accession to the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea Is Unnecessary to Secure U.S. Navigational Rights and Freedoms. The Heritage Foundation. Accessed from: http://www.heritage.org/node/12774/print-display .

20 International Seabed Authority. (1994). Rules of Procedure of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority. Accessed from: http://www.isa.org.jm/files/documents/EN/Regs/ROP_Assembly.pdf.

21 Sorokin, I. (2015). The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea: Why the U.S. Hasn’t Ratified It and Where It Stands Today. Berkeley Journal of International Law Blog. Accessed from: http://berkeleytravaux.com/un-convention-law-sea-u-s-hasnt-ratified-stands-today/.

22 US Department of State. (2017). Maritime Security and Navigation. Bureau of Public Affairs. Accessed from: https://www.state.gov/e/oes/ocns/opa/maritimesecurity/

23 Kuok, L. (2016). The U.S. FON Program in the South China Sea: A lawful and necessary response to China’s strategic ambiguity. Brookings Institution. Accessed from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-US-FON-Program-in-the-South-China-Sea.pdf#page=3.

24 Standifer, C. (2017). A Brief History of U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operations in the South China Sea. USNI News. Accessed from: https://news.usni.org/2017/05/29/brief-history-us-freedom-navigation-operations-south-china-sea

25 Kuok, L. (2016). The U.S. FON Program in the South China Sea: A lawful and necessary response to China’s strategic ambiguity. Brookings Institution. Accessed from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-US-FON-Program-in-the-South-China-Sea.pdf.

26 Freund, E. (2017). Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea: A Practical Guide. Harvard Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Accessed from: https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/freedom-navigation-south-china-sea-practical-guide .

27 United States Department of State. (2014). Limits in the Sea: US Responses to Excessive National Maritime Claims. Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs.

28 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (2002). Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. Accessed from: http://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-2.

29 Duong, H. (2015). A Fair and Effective Code of Conduct for the South China Sea. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Accessed from: https://amti.csis.org/a-fair-and-effective-code-of-conduct-for-the-south-china-sea/.

30 ASEAN. (2002). Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. National University of. Accessed from: http://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-2.

31 Li, M. (2014). Managing Security in the South China Sea: From DOC to COC. Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Accessed from: https://kyotoreview.org/issue-15/managing-security-in-the-south-china-sea-from-doc-to-coc/ .

32 The Strait Times. (2017). Asean, China adopts framework of code of conduct for South China Sea. Accessed from: http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/chinas-foreign-minister-says-maritime-code-negotiations-with-asean-to-start-this-year.

33 Corrales, N. (2017). ‘Code of Conduct framework not instrument to territorial settle disputes.’ The Inquirer. Accessed from: http://globalnation.inquirer.net/159293/code-conduct-framework-not-instrument-settle-territorial-disputes.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Dancel, R. (2017). Framework of South China Sea code skirts thorny issues with China. The Straits Times. Accessed from: http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/framework-of-south-china-sea-code-skirts-thorny-issues-with-china.

37 Wignaraja, G., Collins, A. and Kannangara, P. (2018). Is the Indian Ocean Economy a New Global Growth Pole?. Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies. Accessed from: https://lki.lk/publication/is-the-indian-ocean-economy-a-new-global-growth-pole/.

38Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Indian Ocean Rim Association. (2017). Jakarta Concord: Promoting Regional Cooperation for a Peaceful, Stable, and Prosperous Indian Ocean. Accessed from: http://www.kemlu.go.id/Buku/JAKARTA%20CONCORD_FINAL_not%20signed.pdf.

41 Department of International Relations and Cooperation. (2017). Jakarta Concord: Promoting Regional Cooperation for a Peaceful, Stable, and Prosperous Indian Ocean. Republic of South Africa. Accessed from: http://www.dirco.gov.za/docs/2017/iora0309a.pdf.

42 International Ocean Rim Association. (2017). IORA Action Plan 2017-2021. Accessed from: http://www.kemlu.go.id/Buku/IORA%20Action%20Plan.pdf.

43 United Nations. (1971). Resolutions adopted by the General Assembly during its Twenty-Sixth Session. Accessed from: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/26/ares26.htm.

44 United Nations. (1979). Implementation of the Declaration of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace. Accessed from: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/34/a34res80.pdf.

45 United Nations. (1976). Supplementary Agreement between Sri Lanka and India on the Extension of the Maritime Boundary between the two Countries in the Gulf of Mannar from Position 13m to the Trijunction Point between Sri Lanka, India and Maldives (Point T). Accessed from: http://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/LKA-IND1976TP.PDF.

46 U.S. Department of State. (1978). Limit in the Seas: Maritime Boundaries India-Sri Lanka. Accessed from: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/58833.pdf.

47 Klein, Natalie. (2017). Law of the Sea and Dispute Resolution: Perspectives for Sri Lanka [Lecture]. Foreign Policy Forum. Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute. Colombo. Accessed from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANlC6S0GzYg.

48 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2016). UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme. Accessed from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/index.html?ref=menuside.

49 United Nations. (1971). Declaration of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace. Resolution 2832 (XXVI). Accessed from: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/34/a34res80.pdf.

Abbreviations

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone

FONOP Freedom of Navigation Operations

DOC Declaration on the Conduct

CoC Code of Conduct

∗Myra Sivaloganathan is a Global Associate at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). The author acknowledges the valuable input of Dr. Natalie Klein, and Daniella Kern for their research assistance. The opinions expressed in this Explainer, and any errors or omissions, are the author’s own.