April 2, 2019 Reading Time: 6 minutes

Reading Time: 6 min read

Reading Time: 6 min readImage Credits: UN Women/Flickr

Shihan Maharoof*

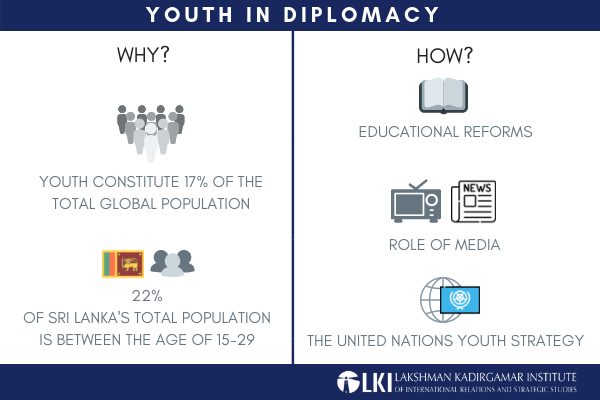

Youth constitute 16% of the world’s population, and these numbers are projected to increase to 17% by 2030.1 In addition, young people today are connected to each other like never before, and are a core demographic in the using and building of disruptive new technologies, global social and clean energy networks. However, youth have very little voice in development programmes, peace negotiations, and most international and domestic political decision-making, despite their growing demographic and economic significance. It is, therefore, imperative that youth are given the opportunity to engage with international institutions and initiatives and contribute their ideas to resolve global issues. It’s evident that if youth step up to mobilise their nation’s potential to move forward in the right direction, they can create a significant impact on the nation’s transformation in the international arena.

Youth aged 15 to 29 constitute 22% of Sri Lanka’s total population,2 and it is high time Sri Lankan youth are allowed to share their opinions and ideas on policymaking and foreign diplomacy, as the former and current generations of leaders—with very few exceptions—have proven themselves incapable of ‘walking the talk.’ The trauma of a civil war that spanned almost three decades has left its scars on society. Youth from war-affected regions are left disillusioned by the lack of inclusion in most international and domestic development programs that make decisions on their behalf. A closer examination of the recent surge of ethnic conflicts notes that youth were involved in instigating some of these events.

The scope for youth in international engagement is vast, diverse, and untapped. Sri Lanka should consider its past and the looming issues of youth-led extremism and violence as an opportunity to take a more proactive role in countering youth issues by setting up a platform that enables youth engagement in diplomacy and international affairs. It is necessary to facilitate the younger generations with appropriate skills required to excel in the field of international relations. Investing in these young agents of change definitely offers the potential of a tremendous multiplier effect.

Sri Lankan youth-led organisations played a pivotal role in Tsunami Assistance and Relief Processes during several natural disasters. Therefore, providing younger generations the opportunity to pioneer and implement diplomatic and economic initiatives should be a long-term vision, as the future development and longevity of a nation is ultimately in the hands of youth. They would possess more responsibility for the decisions and initiatives they present as it directly reflects on their own future.

A key policy measure required in facilitating youth engagement is educational reform. However, the progress on this front has not been promising, particularly in the developing world. In Sri Lanka, the secondary school curriculum does not adequately cover international politics and diplomacy, leaving youth – notably those from rural areas – unaware of the significance of foreign relations and the international community in determining Sri Lanka’s prosperity and political stability. Such issues are further compounded by the lack of facilities to accommodate all students that qualify for tertiary education, leading to only 9% of all eligible students being admitted to universities.3

The lack of English language skills is another key factor that discourages youth involvement in foreign affairs. Only 10% of secondary students master spoken English,4 while only 1% of students exhibit the required competency in written English.5 These skills are furthermore restricted to Colombo and other urban areas, while excluding the rural youth due to lack of awareness, exposure, proper guidance and mentoring. Therefore, much needs to be done on this front before Sri Lankan youth are adequately prepared as a whole to engage proactively and confidently with issues of foreign policy. One such area that requires attention would be the “International Youth Relations” division of the Youth Parliament, at present the youth parliament does not cover international relations and diplomatic ties in a deeper sense. Expanding the “International Youth Relations” division’s activities beyond mere “Youth Exchange Programmes” would make their contribution towards the nation’s development more productive and efficient.

Media, both social and mainstream, has the potential to inspire, given its considerable influence on society, and plays a critical role in keeping youth informed on global issues in an effective manner. However, the question remains – has the role of media been more active in manipulating youth rather than moulding them in the right manner? As social media is often used for propaganda and mainstream media is influenced by political motives, it is much easier to instigate than inspire.

Youth radicalization and exploitation does not stop at borders. Social media and other modern means of communication have enabled terrorist groups and individuals to promote their extremist ideologies6 amongst youth across the globe with ease. Now more than ever, the media has a high level of responsibility to maintain the integrity of information disseminated to keep youth informed about the necessity of their engagement in effective diplomacy, while ensuring that they are not influenced by exposure to extremist ideologies.

The United Nations Youth Strategy7 is the first attempt at a framework to guide the international community with regard to youth involvement, and reaffirms the UN’s message that young people are “an essential asset worth investing in.” The strategy incorporates the role of youth into the global sustainability agenda via three key pillars: peace and security, human rights, and sustainable development. At its core, the strategy aims to provide a blueprint for joint initiatives and implementation of effective practices before it is too late. It also outlines the unique position of the UN to challenge and support states to ensure protection and support for young people, and provides a platform through which their “needs can be addressed, their voice can be amplified, and their engagement can be advanced.”

States could further realise the goals articulated in the UN Youth Strategy by creating networks to educate and involve youth in activities related to global trade, diplomacy, sustainability and peace-building. One such area that requires attention would be the “International Youth Relations” division of the Youth Parliament,8 at present the youth parliament does not cover International Relations and Diplomatic ties in a deeper sense. Expanding the “International Youth Relations” division’s activities beyond mere Youth Exchange Programmes9 would make their contribution towards the nation’s development more productive and efficient. Indonesia, for example, Indonesia has established Indonesian Youth Diplomacy (IYD),10 a youth-run, youth-led programme that raises awareness and builds capacity among Indonesians. Meanwhile in Sri Lanka, platforms like the Sri Lanka Model United Nations (SLMUN) provide youth an opportunity to learn the art of diplomacy and conflict resolution. SLMUN is additionally committed to expanding its role through the Vision 202011 programme.

It is crucial that successful initiatives receive both financial and political support. Furthermore, much remains to be done in areas such as educational reforms. However, these are post facto initiatives that address existing issues. The more challenging goal will be enacting long-term policy reforms that empower youth and provide them with skill sets to confidently navigate the world of international politics, before negative consequences of lack of youth engagement in diplomacy manifest around the world.

1Indonesian Youth Diplomacy. (2019). Meet the Diplomats — Indonesian Youth Diplomacy. [online] Available at: http://www.indonesianyouthdiplomacy.org/meet-the-diplomats/

[Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

2Global Development Index Report. (2016). [pdf] The Commonwealth, p.46.

Available at: http://cmydiprod.uksouth.cloudapp.azure.com/sites/default/files/2016-10/2016%20Global%20Youth%20Development%20Index%20and%20Report.pdf#page=46

[Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

3Liyanage, K. (2014). Education System of Sri Lanka: Strengths and Weaknesses. [ebook]

Available at: http://www.ide.go.jp/library/Japanese/Publish/Download/Report/2013/pdf/C02_ch7.pdf

[Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

4Liyanage, K. (2014). Education System of Sri Lanka: Strengths and Weaknesses. [ebook]

Available at: http://www.ide.go.jp/library/Japanese/Publish/Download/Report/2013/pdf/C02_ch7.pdf [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

5Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-Extremism: Isis and the Power of Social Media. Society, 54(2), pp.138-149. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

[Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

6Ibid

7Youth 2030 – Working with and for Young People. (2019). [ebook] United Nations Youth Strategy. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/18-00080_UN-Youth-Strategy_Web.pdf [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

8National Youth Services Council. (2019). Sri Lankan Youth Parliament. [online] Available at: http://www.nysc.lk/aboutParliament_e.php [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

9National Youth Services Council. (2019). International Youth Relations Division. [online] Available at: http://www.nysc.lk/foriRelation_e.php [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

10Indonesian Youth Diplomacy. (2019). Meet the Diplomats — Indonesian Youth Diplomacy. [online] Available at: http://www.indonesianyouthdiplomacy.org/meet-the-diplomats/ [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

11National Youth Model United Nations. (2019). Vision 2020 – National Youth Model United Nations. [online] Available at: http://www.nymunsl.org/vision-2020/ [Accessed 6 Mar. 2019].

*Shihan Maharoof is a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, nor do they necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated. This article was originally published in the Daily Mirror.