November 12, 2018 Reading Time: 5 minutes

Reading Time: 5 min read

Reading Time: 5 min readImage Credit: efesenko/DepositPhotos

Joan Moonesinghe*

The Basel Capital Concordat, when it was first introduced as Basel I almost two decades ago, was aimed at harmonising bank capital globally. It is, essentially, a capital regulation to ensure that banks, which are inherently highly leveraged financial institutions, have a minimum level of capital relative to their risk exposures.

Basel I was a one-size-fits-all capital standard against credit risk (the core banking risk). It, therefore, did not have any form of risk differentiation. Basel II, however, introduced market risk and operational risk, and permitted risk differentiation with the onus passed onto banks to measure counter-party risk (using internal models) in the recognition that not all counterparties pose the same risk. In addition to risk differentiation, Basel II added supervisory review and market discipline, making it a three-pillar formula. Basel II also mandated banks’ Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Plan (ICAAP) to take into consideration such sources of risk that are not part of Pillar 1 and which may, therefore, be difficult to quantify. Moreover, large organisations were required to develop a comprehensive framework to assess the overall adequacy of their capital allocation with regards to the key risks their business model is exposed to, and to elaborate a capital planning process aligned with their strategic and business plan.

However, Basel II’s complexity led most bank regulators to be preoccupied with it to the detriment of dealing with more fundamental macro-prudential problems unfolding in the market. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 eventually proved that Basel II had failed to provide the capital buffers necessary to prevent the failure of several international banks as well as many Domestic Systematically Important Banks (D/SIBS – predominantly in the UK and Europe). Basel III,1 therefore, was developed as the response of the Basel Committee – the global standard setter for financial institutions – to the GFC.

On the basis of the three fundamental components to Basel III, the Common Equity Tier I (CET 1) and total capital ratios, the Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB) and the short-term Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) have all been integral components of the prudential regulatory framework in this country from the inception of bank regulation.

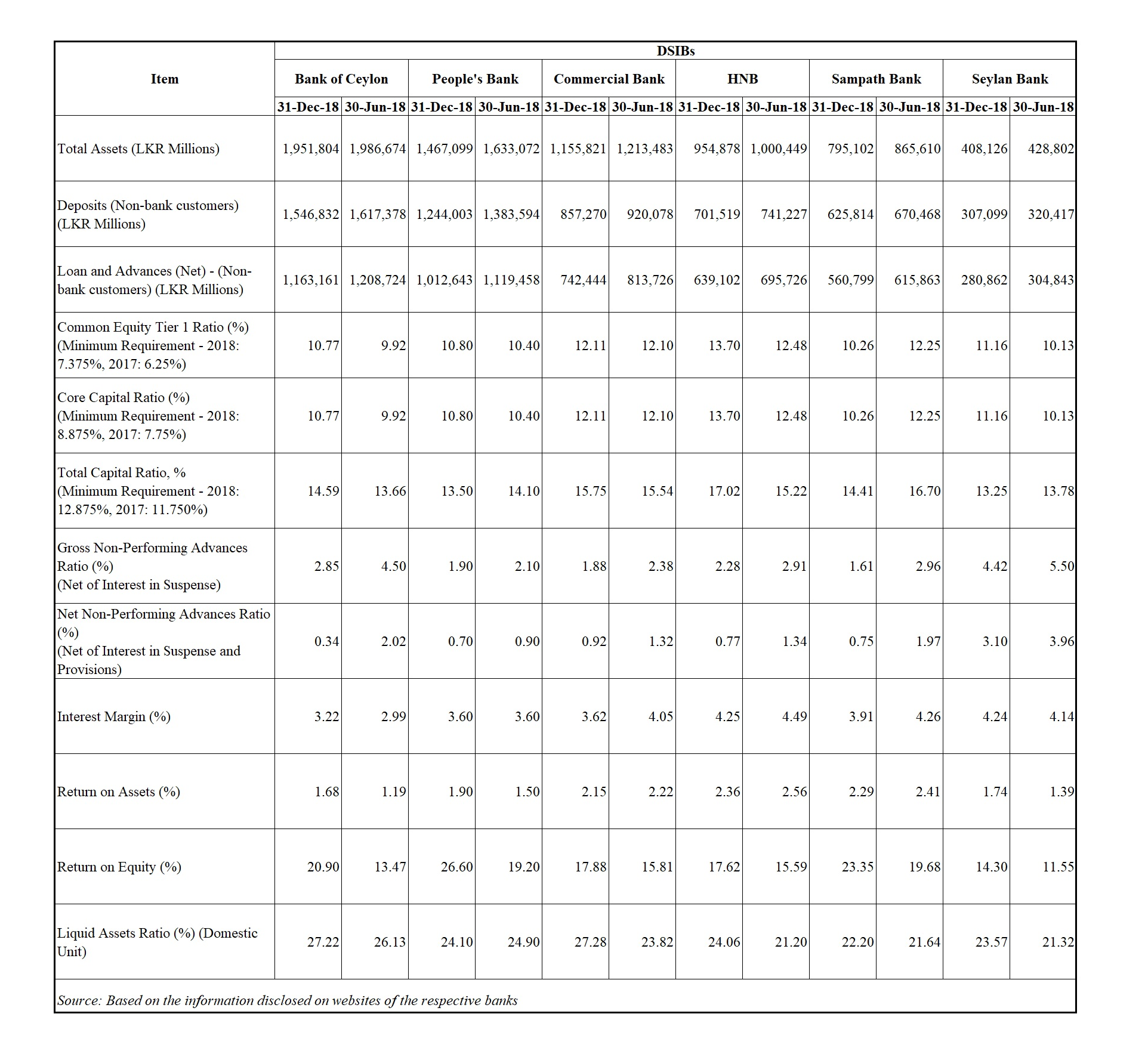

If the Basel standards are indeed the internationally acceptable benchmark for measuring the resilience of a country’s banking system to withstand external shocks – like those that reverberated throughout the world in the last GFC – there is convincing evidence that Sri Lanka’s SIBs (which represent over 75% of total banking assets in the Sri Lankan financial system) are well-equipped with adequate capital buffers to weather these shocks. This conclusion is based on:

In addition, Fitch affirmed the ratings on nine Sri Lankan banks (including the specialised banks NSB and DFCC) as “stable” last month. The key ratings drivers were:

In addition, Fitch affirmed the ratings on nine Sri Lankan banks (including the specialised banks NSB and DFCC) as “stable” last month. The key ratings drivers were:

The importance of the ICAAP discipline is, therefore, profound for the banks (as it would be for the regulators) to ensure that asset expansion moves in sync with adequate capital and prudent profit retention policies; and

Fundamental to the above is the solid foundation of the sound regulatory and supervisory framework that has been in place in the country for well over half a century, and which has been well ahead of the Basel regulations. This framework reflects the superior wisdom and ability of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, working in collaboration with the banking system, to ensure that the Sri Lankan banks are well equipped to weather any external shocks without much balance sheet pressure.

In conclusion, Basel III was primarily intended for the internationally active banks which were affected by the GFC in highly developed regimes where the basic prudential regulations were not in place, where capital was severely compromised, and where risk exposures were highly excessive (to real estate and derivatives). We can be satisfied that the Sri Lankan banks, and indeed most banks in the Asian region, are well ahead of the Basel III curve for the reason that they are well regulated and prudently managed with adequate shock-absorbing capacity.

1 Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2018). Basel III: International Regulatory Framework for Banks. [online] Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3.htm [Accessed 9 Nov. 2018].

2 McKinsey & Company. (2018). Basel III: The Final Regulatory Standard. [online] Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/basel-iii-the-final-regulatory-standard [Accessed 9 Nov. 2018].

*Joan Moonesinghe is a Fellow and Associate of the Chartered Institute of Bankers, London, and an Associate of the Institute of Bankers Sri Lanka. She is also former Director of Bank Supervision, Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, nor do they necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.