August 7, 2020 Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 min read

Reading Time: 9 min read

Image Credits: Renato Gizzi/flickr

*Dr. Anuji Gamage

The world has witnessed many pandemics throughout history. As humans have travelled across the globe, infectious diseases have followed. One of the most fatal pandemics in human history, the Bubonic Plague, which is also known as Black Death (1347-1351) claimed 200 million human lives. Smallpox (in 1520) caused 56 million deaths, and Spanish flu (from 1918 to 1919) caused 40 to 50 million deaths. Pandemic influenza mortality is reportedly 1 to 3 % of the world’s population during the H1N1 pandemic in 1918 and 0.03% during the H3N2 pandemic in 1968. More recently, the H1N1 pandemic during 2009-2010 caused 51,700 to 575,400 deaths globally. The global mortality rate of the H1N1 influenza pandemic was estimated to be between 0.001 to 0.007 %.

The WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared, “Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly. It is a word that, if misused, can cause unreasonable fear, or unjustified acceptance that the fight is over, leading to unnecessary suffering and death. We have rung the alarm bell loud and clear.”1 This LKI Blog discusses the global and local scientific evidence on containing COVID- 19 while emphasizing on the progress, pattern, and new trends related to the pandemic.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus or COVID- 19 (previously known as 2019-nCoV) is making a substantial impact on human lives and threatens global stability and security due to its dramatic spread.2 The virus was identified as the cause of an epidemic of respiratory tract illness which was first detected in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. This virus was never previously identified in either animals or people. The genetic combination of the virus is closely related to pangolins. They may have been transmitted to a human, either directly or through an intermediary host such as civets or ferrets.

On 12th January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) tentatively named this new virus as the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV). On 30th January 2020, at the second meeting of the Emergency Committee convened by the WHO Director-General under the rules of the International Health Regulations, declared the outbreak of novel coronavirus 2019 in the People’s Republic of China a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. On 11th February 2020, the WHO formally re-named the disease triggered by 2019‐nCoV as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19).3 On 11th March 2020, the WHO finally declared the coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic.

How the world responds to a pandemic depends on five questions. The virulence of the infectious agent, route and duration of transmission, basic reproduction number/force of transmission, availability of treatment, and the availability of a vaccine. There is still neither a treatment nor a vaccine available to fight the disease. However, the other questions have answers.4

According to Wu and McGoogan, among 72,314, COVID- 19 cases reported to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC), 81% were mild (absent or mild pneumonia), 14% had severe (hypoxia, dyspnoea, >50% had lung involvement within 24-48 hours , 5% were critical (shock, respiratory failure, multiorgan dysfunction), and 2.3% were fatal.5 The case fatality rate rose with age and in people aged 80 years and above it was around 15%. As reported, some of the common symptoms were fever, cough, myalgia, fatigue. Some of the less-common symptoms were headache, sputum production, diarrhoea, malaise, and shortness of breath/dyspnoea, and respiratory distress. The most common severe manifestation of COVID- 19 appears to be pneumonia.

The basic reproduction number (R0 – indication of the transmissibility of a virus, representing the average number of new infections generated by an infectious person in a totally naïve population)/ or the force of transmission is estimated to be 3.28 on average. This is the key concept of how infections propagate when its put into a non-immune population.6 Effectiveness of control measures is shown by the reduction of R; If R0 >1, it can be interpreted that the number infected is likely to increase, and if R0<1 the transmission is likely to die out.7

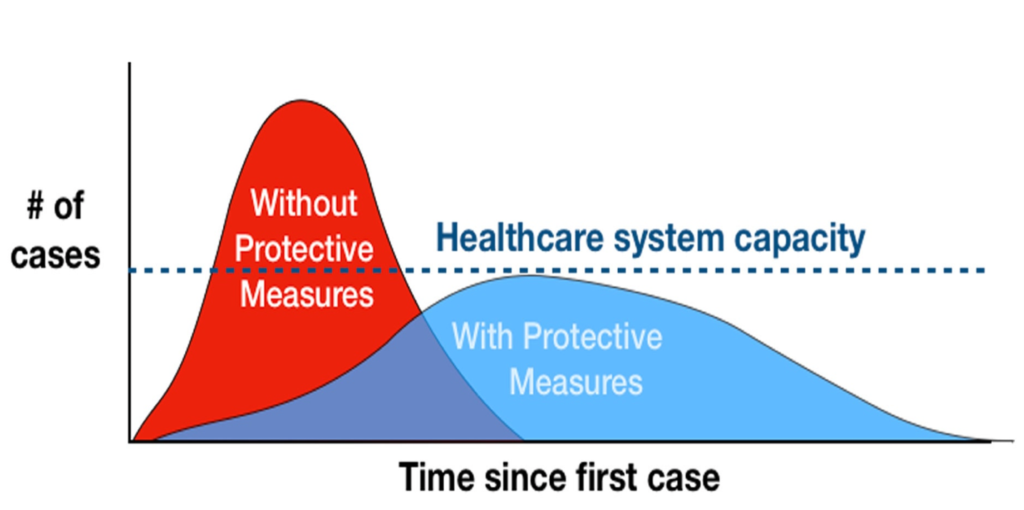

In a pandemic, the ultimate goal is to halt the spread or maintain a zero-local transmission. In the absence of drugs or a vaccine, countries have to rely on the public health measures and different countries adhere to different measure in the fight against this global threat. Maintaining a flattened curve or slowing down the acceleration of the number of cases in a community (as opposed to a surge of COVID infection) is essential during a pandemic. Failing to do so would likely to overwhelm the healthcare system’s capacity to deliver the services to those with the disease. In addition to the above countries should take measures to stop a surge while at the same time increasing the capacity of the healthcare system.

Figure 1: Flattening the Curve8

Suppression strategies aim to minimize spread and thereby the number of cases to an absolute minimum for as long as possible. This requires early instigation of control interventions. Suppression strategies include society-wide control interventions, such as social distancing, hygiene measures, and lockdowns. These can delay an outbreak, given that control measures are adhered to. However, this does not result in herd immunity and, therefore, will not prevent an epidemic. On the other hand, mitigation strategies aim to protect the most vulnerable people in the population (combining isolation of suspect cases, quarantining individuals suspected of carrying the disease, and social distancing of the elderly and others at most risk of severe disease) to control an epidemic so that herd immunity can be acquired by the rest of the population. Hence, mitigation allows the infection to spread at a controlled rate, ensuring that there will be no overburdening of disease at the hospitals. The suppression strategy could be converted to a mitigation strategy. Suppression buys time until a vaccine and/or treatment becomes available.9. There are pros and cons of both suppression and mitigation measures. Suppression, too, has costs as it leads to substantial economic and social costs, which negatively impacts a country in the shorter and longer-term.

On the other hand, mitigation will never protect those who are at risk of death, thus the mortality rate will still be high.10 The elimination approach, in contrast to suppression and mitigation, reverses the spread by early interruption of disease transmission using vigorous interventions. However, until elimination is reached suppression the next best strategy as it would have the largest impact on the healthcare system. All in all, there needs to be a clear plan to face this deadly disease and move out of lockdown and achieving zero transmission to achieve normal economic and societal functions.

Prof. Chris Whitty11 points out that an outbreak could result in high mortality and morbidity in the following ways; direct morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19 infection, indirect morbidity and mortality due to health systems being overwhelmed, indirect deaths due to the delay of non-urgent services such as screening, etc., or people not seeking health due to the avoidance of hospitals, and most importantly the suppression and mitigation measures put in place by the government causing a wider economical and societal impact leading to poverty and deprivation which is directly linked to ill health.

Epi curves depict the number of infected cases by day, week, or month and it helps to evaluate the current situation and facilitate predictions. The growth of the epidemic is an important measure of the severity, which is closely related to the R0.12 According to WHO, the dynamics of epidemic or Pandemic diseases typically occur in 4 phases.13

Figure 2: Distribution of COVID-19 Positive Cases and the Public Health Measures taken in Sri Lanka14

As of 13th May 2020, there are 4,088,848 confirmed cases with 283,153 deaths worldwide. In contrast, 889 confirmed cases have been reported in Sri Lanka with 9 deaths. As of 13th of May 2020, Sri Lanka is still in Phase 3 of the epidemic as cases are occurring in clusters and the country is returning to normalcy from the pandemic.15 The approach of the Government of Sri Lanka to flatten the curve has been ‘a whole-of-government, whole-of-society approach’ where “ “proactive intervention to prevent any outbreak of COVID-19 within Sri Lanka “ was initiated.

The community strategies observed in Sri Lanka are mainly aimed at suppression and mitigation, which are primarily to reduce the R0. They are:

The spread of COVID‐19 has developed into a worldwide pandemic, which is still evolving. There are many unknowns and these include the proportion of the population infected but displays no symptoms, how long would a person’s immunity last, and, therefore potential re-infection, treatment options, diagnostics, trials, and still very little is understood of the viral behaviour. As such, it might be a little too early for concrete evidence. The endpoint of the COVID-19 is still unseen. Based on the current progress of containment, Sri Lanka sets a global example in managing the outbreak through a ‘whole-of-government approach whole-of-society approach.’ However, we should not be too complacent, as the threat of an epidemic disappears only when it is eliminated from the whole world. Until that during the lifting of public health measures the following should be considered.

It is also important to mention WHO’s contribution as a technical partner during the pandemic. WHO has been the centre of storm and criticism, yet continues to work with governments in battling outbreaks while putting in the effort to develop vaccines and therapeutics to combat the coronavirus. Their service is important and should earn praise. All in all, the government needs to have a clear plan for the dual crisis; health and economics. Collectively, the whole community is facing the anxiety of the unknown and is best addressed by remaining calm, organized, and systematic in our response.

1World Health Organization. (2020). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. [Online] Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 [Accessed 22 April 2020].

2World Bank. (2017). From panic and neglect to investing in health security: financing pandemic preparedness at a national level. World Bank Group. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/979591495652724770/From-panic-and-neglect-to-investing-in-health-security-financing-pandemic-preparedness-at-a-national-level

[Accessed 22 April 2020].

3Sun et al. (2020). Understanding of COVID‐ 19 based on current evidence. Journal of Medical Virology. 92: pp. 548-551.

4Gresham College. (2020). COVID-19: Chris Whitty gives an initial view of the pandemic. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/ [Accessed 6 May 2020].

5Wu, Z & Mcgoogan, J. (2020). Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID- 19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 323(13): pp. 1239-1242.

6Supra note 4.

7Liu et al. (2020). The reproductive number of COVID- 19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. Journal of travel medicine. 27(2).

8Department of Health and Human Services. (2007). Interim pre-pandemic planning guidance: community strategy for pandemic influenza mitigation in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Online] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/community_mitigation-sm.pdf [Accessed 4 May 2020].

9Imperial College London. (2020). Report 9 – Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID- 19 mortality and healthcare demand. [Online] Available at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19/ [Accessed 22 April 2020].

10Ibid.

11Supra note 4.

12Ma, J. (2020). Estimating epidemic exponential growth rate and basic reproduction number. Infectious Disease Modelling. 5: pp. 129-141.

13World Health Organization. (2020). Critical preparedness, readiness and response actions for COVID- 19. [Online] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/critical-preparedness-readiness-and-response-actions-for-covid-19 [Accessed 22 April 2020].

14Epidemiology Unit, Ministry of Health. (2020). Epidemiology Unit. [Online] Available at: http://www.epid.gov.lk/web/ [Accessed 22 April 2020].

15Ibid.

*Dr. Anuji Gamage is a Public Health Specialist and a Senior Lecturer of the Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine at the Sir John Kotalawala Defense University Sri Lanka. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They are not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily represent or reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.