August 14, 2018 Reading Time: 5 minutes

Reading Time: 5 min read

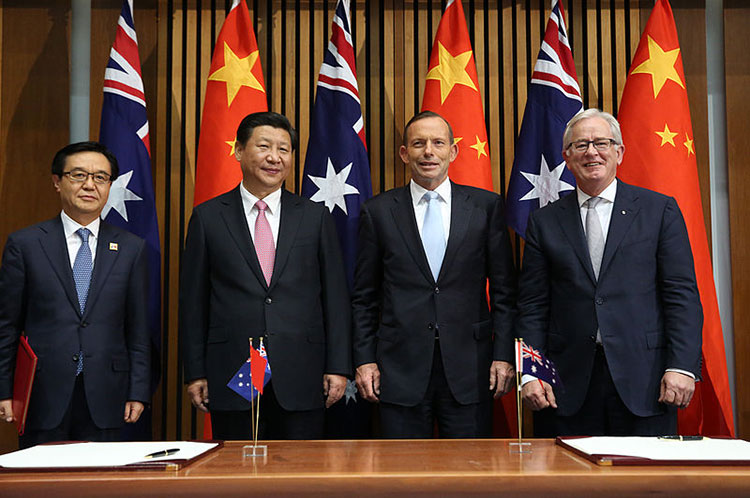

Reading Time: 5 min readImage Credit: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade/ Wikimedia Commons

Heng Wang*

Investment rules are of great significance to China as a leading importer and exporter of capital globally. Chinese investment under its Belt and Road Initiative and recent geopolitical dynamics increasingly require China to provide predictable rules that protect investors.

The recent evolution of China’s investment rules is best tracked in its free trade agreements (FTAs). China has concluded 16 FTAs with 24 countries and regions,1 nearly all of which include investment provisions. Malleability is the most striking feature of China’s investment rules in FTAs. The flexibility with which China approaches its investment agreements will affect the negotiated terms of mega-trade agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership,2 bilateral FTAs such as the proposed China-Sri Lanka FTA,3 and bilateral investment treaties (BITs), particularly the European Union-China BIT.4

Two questions deserve attention: What is the trend of China’s FTA approach to investment? And is China a rule follower, shaker or maker?

Traditionally, China’s trade pacts focus on the protection of foreign investments, without liberalising the flow of such investments. This contrasts with the trade pacts of Western states, which both protect foreign investments of partner countries and liberally permit them. However, China is progressively moving towards investment liberalisation with selected partners – irrespective of the current uncertainty around the potential BIT between the United States and China. It is likely to continue to more frequently provide for ‘pre-establishment national treatment’ (i.e. allow foreign investors to enjoy terms at least as favourable as applying to domestic investors), and for the more liberal ‘negative list’ approach to investments (a system in which foreigner can invest in all fields that are not on the prohibited list without governmental approval, rather than a system of generally requiring approval).

There are several reasons for this progressive approach. Most importantly, investment liberalisation benefits Chinese companies investing overseas (by way of reciprocity). Chinese businesses have repeatedly asked the government to incorporate pre-establishment national treatment into investment treaties. Second, investment liberalisation helps to attract foreign investment to China and boost investor confidence, which is crucial for economic development and increasingly important in the current US-China trade war. Third, investment liberalisation may facilitate domestic reform in China through the force of international obligations, which has been the case since China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation. Last, there are no difficulties in implementing pre-establishment national treatment and a negative list approach in China. The US demanded these aspects during its BIT negotiations with China, and China saw the demands as a useful way to promote reform.

The increased malleability of China’s investment rules is apparent in two areas. The first is in the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS),5 in which investors may bring claims against host state governments under the FTAs. The second is in regulatory autonomy, which affects the rights of host governments to regulate in the public interest, such as for public health.

China’s trade pacts with Australia and South Korea differ significantly in these two areas. The China-Australia FTA (ChAFTA)6 is much stronger than other Chinese FTAs in preserving regulatory autonomy. In relation to the design of ISDS, the ChAFTA ensures that parties to the treaty have more control over ISDS; and in particular, in determining the scope of claims, selecting and regulating arbitrators, and providing interpretation and guidance. Most of these provisions are absent or less developed in the China-Korea FTA.7

This greater malleability is attributable to various factors. First, China is still exploring models for ISDS and regulatory autonomy in its FTAs. Second, China often relies on the proposals of FTA partners in FTA negotiations. It seems that the ISDS clauses in the ChAFTA, for example, reflect rising Australian caution with ISDS. Moreover, China has so far faced only a limited number of ISDS disputes, perhaps because investors and host state governments wish to avoid their potentially corrosive effect on bilateral relations.

China has not been a dominant norm-maker on key investment clauses, and will probably instead remain a rule-shaker in the short-to-medium term. Its FTAs largely build on the proposals of partner countries, as is evident in China’s FTAs with Australia and Korea. The China-Korea FTA and the ChAFTA appear to be affected, at least to some extent, by the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement8 and Australian approaches. This is probably why some key rules in the ChAFTA differ substantially from those in the China-Korea FTA. China’s role as a rule-shaker helps explain why it has not formulated a consistent set of FTA investment clauses. The Chinese paradigm incrementally converges towards deep FTAs—for example, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)9 and the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)10—but detailed norms on investment protection are generally shaped by those who sit across the table.

On the other hand, China is not simply a rule-follower. It has a cautious attitude toward investment liberalisation and what it considers ‘intrusive’ requirements, and it has modified investment clauses when needed. These intrusive requirements pertain to, inter alia, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), labour, and the environment. China prefers to liberalise investment progressively to avoid unintended consequences.

In addition, China has demanded specific investment arrangements in its FTAs. Under the ChAFTA, it secured a more favourable environment for Chinese investment, including an easier threshold for non-SOE investment in Australia to be screened for approval, and related labour mobility provisions for Chinese workers. The screening threshold for non-SOE investment in Australia quadrupled from 0.248 billion AUD to 1.078 billion AUD11. Moreover, to facilitate the mobility of Chinese workers for such investments, a memorandum of understanding on an investment facilitation arrangement (IFA) is included under the ChAFTA. It is the first of its kind granted by a developed country to China and may facilitate the processing of Australian visas under the arrangement.

In the long run, China has the potential to turn itself into a major norm-maker in investment treaties, since investment norms are the fastest developing area of its FTAs. However, continuing issues pose challenges for China. Further, China will probably need the strong support of major economies if it wants to shape new investment norms.

1 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. (2018). Available at: http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/.

2 Association of Southeast Asian Countries. (2016). Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Available at: http://asean.org/?static_post=rcep-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership.

3 Asia Regional Integration Center. (2015). People’s Republic of China-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement. Available at: https://aric.adb.org/fta/peoples_republic_of_china-sri_lanka_free_trade_agreement.

4 European Commission. (2018). China. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/china/.

5 Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2015). Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/investor-state-dispute-settlement-0.

6 Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (2015). China–Australia Free Trade Agreement. Available at: http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/Pages/australia-china-fta.aspx.

7 Asia Regional Integration Center. (2015). People’s Republic of China-[Republic of] Korea Free Trade Agreement. Available at: https://aric.adb.org/fta/peoples-republic-of-china-korea-free-trade-agreement.

8 Office of the United States Trade Representative. U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement. Available at: https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/korus-fta.

9 New Zealand Foreign Affairs and Trade. (2018). Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Available at: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/CPTPP/Comprehensive-and-Progressive-Agreement-for-Trans-Pacific-Partnership-CPTPP-National-Interest-Analysis.pdf.

10 European Commission. (2018). EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/in-focus/ceta/.

11 Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. (2017). Interpretation of the Free Trade Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and Australia. Available at: http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/article/chinaaustralia/chinaaustralianews/201506/22176_1.html.

Wang, H. (2018). An Assessment of the ChAFTA and Its Implications: A Work-in-Progress Type FTA with Selective Innovations? in C. Picker et al (eds). The China-Australia Free Trade Agreement: A 21st Century Model, Hart Publishing [online], 19-41. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2960440

Wang, H. (2016). The Challenges of China’s Recent FTAs: An Anatomy of the China-Korea FTA. Journal of World Trade, Vol. 50, No. 3, 417-446. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2790673;

*Heng Wang is Associate Professor and Co-Director of the China International Business and Economic Law Initiative of the Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Sydney, and University Visiting Professorial Fellow, Southwest University of Political Science and Law. A longer version of this article was published as Heng Wang, The RCEP and Its Investment Rules: Learning from Past Chinese FTAs, The Chinese Journal of Global Governance, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2017, 160-181. He can be reached at heng.wang1@unsw.edu.au, and his Twitter handle is @HengWANG_law. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, nor do they necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.