March 2, 2017 Reading Time: 8 minutes

Reading Time: 8 min read

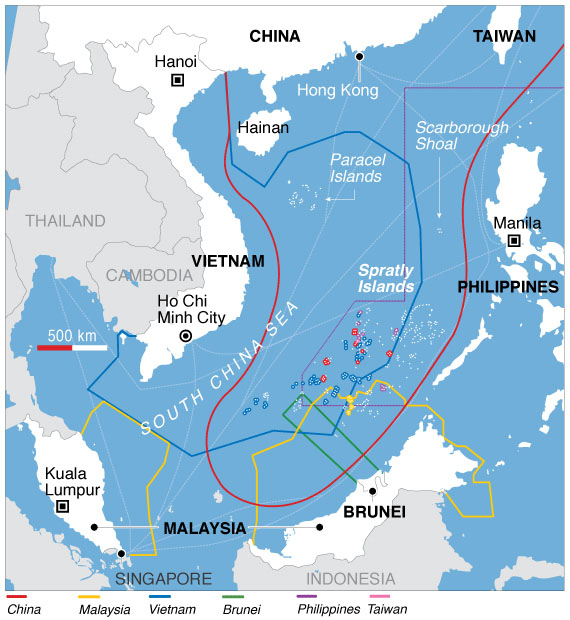

Territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Image Credit – Wikipedia Commons

LKI Research Associate, Anishka De Zylva, visited Yale-NUS College in Singapore on 4th November 2016, where she met Dr. Navin Rajagobal to discuss an ongoing issue in the Indo-Pacific region: disputes in the South China Sea. Her interview of Dr. Rajagobal is part of LKI’s Spotlight Series, which features interviews with experts from around the world on aspects of contemporary international relations.

Dr. Rajagobal joined Yale-NUS, Singapore’s first liberal arts college, in 2014. He currently serves as Director, Academic Affairs, as Head of Studies for the Law and Liberal Arts Double Degree Programme, and as Senior Lecturer in the Division of Social Sciences. His teaching interests include foreign policy and diplomacy, international law and institutions, and international relations. Prior to joining Yale-NUS, he was the founding Deputy Director of the Centre for International Law, a university-wide and interdisciplinary centre for research and capacity-building based at the National University of Singapore.

See below for a lightly edited transcript of the wide-ranging interview with Dr. Rajagobal.

Ms. De Zylva: Dr. Rajagobal, you’ve recently written on the implication of disputes in the South China Sea for the rest of Asia. Let’s start by putting the South China Sea dispute into context.

In your opinion, why is the South China Sea important to trade and security in Asia?

Dr. Rajagobal: The South China Sea is absolutely vital to Asia, and particularly to the South East Asian countries. It is at the core of ASEAN – the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. It is the lifeblood of the trade and economy of many countries in this region; including Singapore and Malaysia. It links China and Japan with the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, and North East Asia to Australia. Much of the world’s shipping and energy supply goes through the South China Sea. It is vital for strategic reasons because of this, but also because of military shipping from the superpowers and other nations that passes through this region, which sits between the Indian and Pacific oceans.

The South China Sea was in the past considered to be mostly high seas with specific islands claimed as territory by some countries. Recently, of course, with the advent of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, there have also been maritime claims in the region. These have caused an increase in tension between the various claimant states. Because China is now a rising power, it is not the same as before; you’re dealing with a major power like China while the other claimant states are much smaller countries; the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.

An added complication is that the smaller claimant states are also members of ASEAN. ASEAN countries recently signed the ASEAN Charter. ASEAN wants to be an effective international and regional organisation, and some of the claimant states like the Philippines and Vietnam would like ASEAN to take a much more active role in their disputes against China. Yet many of the ASEAN countries are major trading partners with China, and this causes some tensions within ASEAN as well.

Ms. De Zylva: The latest phase of the dispute began in 2009, when Malaysia and Vietnam made a joint submission on their competing claims in the southern part of the South China Sea.

Would you say that their submission was made in line with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and how did it trigger the most recent phase of the South China Sea dispute between the Philippines and China?

History of disputes in the South China Sea

Dr. Rajagobal: The dispute itself is fairly old. It can be traced back to the 1940s when China first released the nine-dash-line map; which at that time was the eleven-dash-line map. Some people trace it even further back. At this time many of the South East Asian countries weren’t even independent; they were colonial states. So the dispute has lingered for some time, and there was even armed conflict between China and Vietnam over South China Sea islands at some point.

In the 1980s and 90s, when Deng Xiaoping became the paramount leader of China, he decided to set aside these disputes in favour of mutually beneficial economic development. There were a lot of positive developments in the relations between China and South East Asian countries, including Vietnam and the Philippines, and certainly Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia. And there were a lot of informal and formal consultations, and confidence-building measures, that were taking place at that time to keep this dispute in abeyance.

Malaysia and Vietnam’s joint submission to CLCS

But in 2009, Malaysia and Vietnam made a joint submission to the CLCS, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, to delineate where their continental claims in the South China Sea began and ended. This had the effect of pushing China’s claims out of the core of the South China Sea into the northern periphery.

I don’t think the intention was to ratchet up tensions. Malaysia and Vietnam were just trying to conform to the requirements of UNCLOS, and the deadlines of the CLCS, and to bring their previous claims in line with the law of the sea. But of course China had to react, and part of the official response from China, to reject the Malaysia-Vietnam joint submission, was to attach the nine-dash-line map.

The nine-dash-line map

This was the first time that the nine-dash-line map was attached in an official Chinese publication and released to the world. And I think this took on a life of its own. Previously the map was in the background; it wasn’t official, it wasn’t clear. In international relations, we may call this constructive ambiguity. But now the constructive ambiguity was gone, as this map with its dashes that are not in line with UNCLOS was released in official Chinese communication.

Instead of just being a dispute limited to the South China Sea claimant states and regional countries, it became a concern for everybody. It became a concern for non-claimant South East Asian states who were neighbours; it became a concern to the major shipping and trading powers; it became a concern to the superpower, the United States, and to others who asked, ‘What does this map mean?’

China tried to maintain a bit of constructive ambiguity by not explaining what the map meant. It said everything that’s within the nine-dash-line, including the waters, belonged to China, or something to that effect. This, however, caused a lot of consternation, especially among international lawyers who felt that this did not conform to the law of the sea. And so, international relations experts started saying, ‘Is this China asserting itself because of China’s rise?’ With China becoming a military and economic power, does this mean that China is trying impose its will on the South China Sea?

Transition from a regional issue to an international issue

So from a small regional issue, it became an international concern, and China was cornered into being this big power that is not conforming to international law, and it was put on the defensive. That’s what 2009 was, in my opinion. It ratcheted up the dispute, and caused China to lose some of the goodwill it had before 2009. Before 2009, China-ASEAN relationships were fantastic. The ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement was signed and significant investment from China came into ASEAN. The United States was too focused on the Middle East after 9/11. It ignored the region and China stepped into the breach somewhat. China also took the place of Japan, because Japan was going through economic stagnation. Japan’s Official Development Aid (ODA) to ASEAN countries reduced; while China’s increased.

Everyone was forced to say ‘China, please conform to international law’, and China was saying, ‘Yes, we are…the South China Sea belongs to us according to the nine-dash map.’

So a lot of goodwill was built up and all of that was damaged in 2009 because of China’s response to the joint submission. The nine-dash map that came with the response really made the situation bad, unfortunately. Everyone was forced to say ‘China, please conform to international law’, and China was saying, ‘Yes, we are, but still the South China Sea belongs to us according to the nine-dash map, sorry.’ It was hard for China to retract this map once it was out in the public sphere. How do you say, ‘No we’d only subscribe to it domestically’? That would be very difficult to do because of rising nationalism and the publicity the nine-dash map was generating across the world after 2009.

Ms. De Zylva: So this dispute, which was initially a concern of only six claimant states, morphed into an international issue.

Do you see other Asian countries being drawn into the South China Sea dispute between China and the Philippines?

Dr. Rajagobal: Yes, as I mentioned, the dimension changed from just regional to international when China submitted the nine-dash-line map. Everybody, even those who had no interest in the dispute became concerned, and started asking, ‘What does this mean? Is this China exerting its power as dominant state in the region, or is China trying to unravel the UN Convention on Law of the Sea?’ It was discussed in the news everywhere, and it became a topic of study in international law and international classes everywhere. I don’t think China intended that to happen, but it happened.

The wider question is what kind of power is China going to be in the future? China is certainly going to become a rival to the United States, even a superpower, economically and militarily. Would China be a constructive hegemon, or is it going to be a dominant hegemon which is after territory and so on? So people are looking at the South China Sea as an example of how China might behave in the future, and also to see what’s going on inside China.

We understand that some people in China are conciliatory, wanting a solution, while there are others who might be more hawkish. The hawkish ones, for instance, are saying, ‘We are a rising power, we are a big power, and why are these small countries not listening to us; why are they being upstarts? Is the United States deliberately trying to cause trouble by supporting these smaller countries?’

Of course things have changed now with President Duterte in the picture in the Philippines. He’s courting China now and not the United States, possibly for economic reasons. We’ll see what happens.

Ms. De Zylva: How might other countries in Asia ease potential threats that could arise from the South China Sea dispute, especially threats related to freedom of navigation and trade?

Dr. Rajagobal: Freedom of navigation and trade is important for all countries related to the dispute. It is important for the rising power China as well. The concern, of course, is that nationalism and nationalistic sentiment will overtake rational reason. And some people will decide to engage in conflict for what is essentially, tiny islands, some of which are not even above water during low tide. And there’s some talk about oil in the sea, but we don’t know how much, or how economically viable it is. So, I think confidence-building measures and continued discussions are very important.

The recent decision by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in favour of the Philippines has helped to some extent. It clarified the fact that China was in the wrong and the Philippines was in the right with respect to the nine-dash line map. I don’t think the judgement itself is going to change things on the ground, but at least China got a message that the international community takes international law seriously. Instead of trying to fight it headlong, why doesn’t China accept the decision, and work around it by diplomatically engaging the Philippines and other countries? Maybe setting aside the dispute in favour of mutually beneficial cooperation can be a good idea once again.

Even if both sides do not pull back on their claims, they could engage in joint development agreements on fisheries, or oil and gas, or exploration of these things. This is a possible way of not letting the political and strategic aspects of the dispute overtake economic development priorities and regional stability.

END

You can learn more on Dr. Rajagobal’s views in his article published earlier this year, in The Straits Times, titled ‘The 2009 claims that changed the dynamics in the South China Sea’.

*The opinions expressed in this transcript are the interviewee’s own views and are not the institutional views of LKI.