June 26, 2018 Reading Time: 8 minutes

Reading Time: 8 min read

Image Credit: Kyle Heller/ flickr

This LKI Explainer examines key aspects of maritime piracy. It will also consider options for Sri Lanka to further develop maritime security cooperation at the regional level, to combat piracy.

1. What is Maritime Piracy?

2. Current Trends

3. Responses to Maritime Piracy

4. Opportunities for Sri Lanka

5. Key Readings

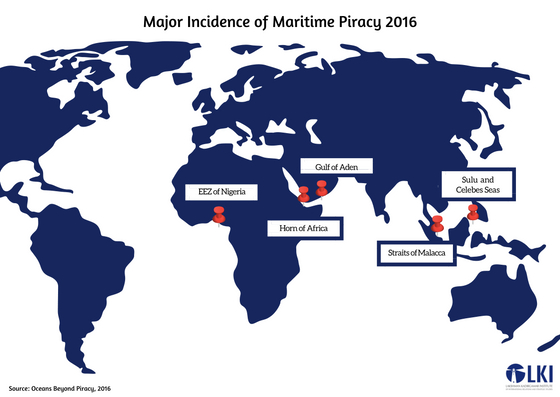

Oceans Beyond Piracy.2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Executive Summary. http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/summary

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.2018. Maritime Crime Programme – Indian Ocean. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/indian-ocean-division.html

Cardiff University and University of Seychelles. Piracy-studies.org: the research portal for maritime security. http://piracy-studies.org/

Williams, P.R. and Pressly, L.2014. ‘Maritime Piracy: A Sustainable Global Solution.’ Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1035&context=jil

International Chamber of Commerce-Commercial Crime Services.2018. IMB Piracy Reporting Centre. https://www.icc-ccs.org/index.php/piracy-reporting-centre

1 United Nations. 2017. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

2Anyiam, H.I. 2014. ‘When Piracy is Just Armed Robbery’. The Maritime Executive [online]. Accessed February 2018: https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/When-Piracy-is-Just-Armed-Robbery-2014-07-19#gs.KwPqwwE

3 United Nations. 1988. Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://www.un.org/en/sc/ctc/docs/conventions/Conv8.pdf

4 Statista. 2018. Number of pirate attacks against ships worldwide from 2009 to 2017. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://www.statista.com/statistics/266292/number-of-pirate-attacks-worldwide-since-2006/

5Sow, M. 2017. Figures of the Week: Piracy and Illegal Fishing in Somalia. Brookings Institution [online]. Accessed February 2018: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2017/04/12/figures-of-the-week-piracy-and-illegal-fishing-in-somalia/

6 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in West Africa 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/west-africa

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Robbery Against Ships in Asia 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/se-asia

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Tharoor, I. 2009. How Somalia’s Fishermen Became Pirates. Time. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1892376,00.html

14 Knaup, H. 2008. The Poor Fishermen of Somalia. Spiegel. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/prelude-to-piracy-the-poor-fishermen-of-somalia-a-594457.html

15 Ridout, T. A. n.d. Somalia is Not a State. The Huffington Post. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://www.huffingtonpost.com/timothy-a-ridout/somalia-is-not-a-state_b_894734.html

16 Okafor, U. 2014. The Nigerian Government Is a Greater Threat to its People Than Boko Haram. The Huffington Post. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/udoka-okafor/nigerian-government-corruption-_b_5686842.html

17 Council on Foreign Relations. 2009. Abu Sayyaf Group (Philippines, Islamist separatists). [online] Accessed February 2018:https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/abu-sayyaf-group-philippines-islamist-separatists

18 United Nations. (2017). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

19 Ibid.

20United Nations. 2008. Security Council Condemns Acts of Piracy, Armed Robbery off Somalia’s Coast, Authorizes for Six Months ‘All Necessary Means’ to Repress Such Acts. United Nations Security Council Press Release [online]. Accessed February 2018: https://www.un.org/press/en/2008/sc9344.doc.htm

21 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2014. Maritime Crime Programme – Indian Ocean. [online] Accessed February 2018: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/indian-ocean-division.html

22 United Nations. 2017. Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2383 (2017), Security Council Renews Authorization for International Naval Forces to Fight Piracy off Coast of Somalia. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/sc13058.doc.htm

23 Combined Maritime Forces. 2018. CTF 150: Maritime Security. [online] Accessed February 2018: https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-150-maritime-security/

24 Combined Maritime Forces. 2018. CTF 151: Counter Piracy. [online] Accessed February 2018: https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-151-counter-piracy/

25 European Naval Force Somalia. 2017. European Naval Force Somalia Operation Atalanta. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://eunavfor.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017May_Booklet-Eng.pdf

26Chan, F. and Soeriaatmadja, W. 2017. ‘Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines launch joint operations in Sulu Sea to tackle terrorism, transnational crimes’. Straits Times [online]. Accessed February 2018: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/indonesia-malaysia-and-philippines-launch-joint-operations-in-sulu-sea-to-tackle-terrorism

27 Lean, C. K. S. 2016. CO16091 | The Malacca Strait Patrols: Finding Common Ground. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/co16091-the-malacca-strait-patrols-finding-common-ground/#.Wn0upVT1XdQ

28 International Maritime Organisation. 2010. Amendments to the International Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue (IAMSAR) Manual. [online] Accessed February 2018:http://www.imo.org/blast/blastDataHelper.asp?data_id=29093&filename=1367.pdf

29Saberwal, A. 2016. Time to Revitalise and Expand the Trilateral Maritime Security Cooperation between India, Sri Lanka and Maldives. Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://idsa.in/idsacomments/trilateral-maritime-security-cooperation-india-sri-lanka-maldives_asaberwal_220316

30Indian Ocean Rim Association. 2017. IORA Action Plan 2017-2021. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia. [online] Accessed February 2018:http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/iora-action-plan-2017-2021.pdf

31 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in East Africa 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/east-africa

32 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in West Africa 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/west-africa

33 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in East Africa 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/east-africa

34 Oceans Beyond Piracy. 2016. The State of Maritime Piracy 2016: Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in West Africa 2016. [online] Accessed January 2018: http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/reports/sop/west-africa

35Waidyatilake, B. 2017. Maintaining Momentum: Sri Lanka’s Strategy in the Indian Ocean Rim Association South Asian Voices. [online] Accessed February 2018:https://southasianvoices.org/maintaining-momentum-sri-lankas-strategy-iora/

36 Saberwal, A. 2016. Time to Revitalise and Expand the Trilateral Maritime Security Cooperation between India, Sri Lanka and Maldives.

37 Christopher, C. 2017. Intelligence Coordination Centre to combat transnational crime in South Asia. The Sunday Times. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.sundaytimes.lk/171119/news/intelligence-coordination-centre-to-combat-transnational-crime-in-south-asia-269351.html

38 Thomas, K. C. 2017. Regional drug intelligence centre to be set up Facilitated by UNODC. Ceylon Today. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.ceylontoday.lk/print20170401CT20170630.php?id=34820

39 Edirisinghe, R. 2008. Launching of 100th indigenous special designed fighting boat by the Sri Lanka Navy. The Asian Tribune. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.asiantribune.com/?q=node/13183

40Povlock, P.A. 2011. ‘A Guerrilla War at Sea: The Sri Lankan Civil War’. Small Wars Journal [online}. Accessed February 2018: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a549049.pdf

41Defenceweb. 2016. Nigeria receives patrol boats from Sri Lanka. Defenceweb [online]. Accessed February 2018: http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=43401%3Anigeria-receives-patrol-boats-from-sri-lanka&catid=51%3ASea&Itemid=106

42 Fish, T. 2014. Sri Lankan Navy is being re-shaped says Vice-Admiral Colambage. Re-printed in Thuppahi’s Blog from Jane’s Defence Weekly. [online] Accessed February 2018: https://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2014/04/04/sri-lankan-navy-is-being-re-shaped-says-vice-admiral-columbage/

43 Ceylon Association of Shipping Agents. 2017. Importance of maritime security in journey to become a maritime hub. The Daily Mirror. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/Importance-of-maritime-security-in-journey-to-become-a-maritime-hub-142522.html

44 The Island. 2017. Navy Chief: Navy to increase sea marshals for foreign ships. [online] Accessed February 2018: http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=170546