Understanding IUU Fishing

October 20, 2022 Reading Time: 8 minutes

Reading Time: 8 min read

Image Credit – U.S. Navy photo by Kwabena Akuamoah-Boateng/Released, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Alisha Rajaratnam*

This LKI Explainer, ‘Understanding IUU Fishing’ examines the nature of Illegal, unreported & unregulated fishing (IUU). It also considers Sri Lanka’s efforts in managing IUU fishing.

Contents

- What is IUU Fishing?

- Global IUU fishing Trends

- Impacts of IUU fishing

- Potential responses to IUU fishing

- Sri Lanka and IUU fishing

- Key Readings

- Notes

1.What is IUU Fishing?

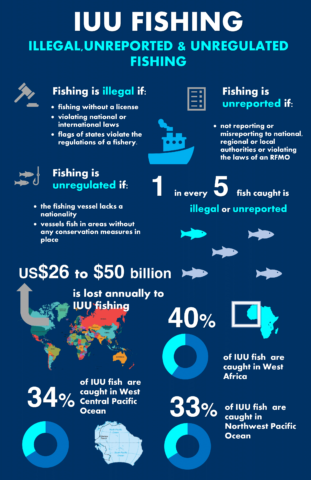

IUU fishing is a broad umbrella used to describe a wide range of fishing malpractices, namely, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. On the 2nd of March 2001, the FAO International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IPOA-IUU) was brought into action at the Twenty-fourth Session of Committee of Fisheries (COFI). As per the IPOA-IUU1, this term can be explicated in the following way:

| | Fishing is |

| Illegal if | Unreported if | Unregulated if |

foreign vessels fish without permission in waters under the jurisdiction of another state, violate national and or international laws and regulations of the relevant fishery or of a regional fisheries management (RFMO), vessels flying the flags of States violate the conservation and management measures of a fishery.

Some examples of illegal fishing include, a foreign vessel entering another nation’s water to fish without a license, fishing in banned areas, violating national and international laws by using prohibited gear, fishing over quotas and fishing for protected species.

| foreign vessels fish without permission in waters under the jurisdiction of another state, violate national and or international laws and regulations of the relevant fishery or of a regional fisheries management (RFMO), vessels flying the flags of States2 violate the conservation and management measures of a fishery.

Some examples of illegal fishing include, a foreign vessel entering another nation’s water to fish without a license, fishing in banned areas, violating national and international laws by using prohibited gear, fishing over quotas and fishing for protected species. | vessels without nationality fish in an area managed by an RFMO, vessels flying the flags of a state fish in RFMO waters to which the state is not a party to, vessels fish in areas outside the purview of any conservation or management measures in place. |

2. Global IUU Fishing Trends

2.1 Trends in IUU Fishing

- The highest proportion of IUU fishing occurs off the coast of West Africa as approximately 40 percent of fish caught are from IUU fishing.3

- West African states such as Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Mauritania experience losses of approximately 3 billion USD annually. 4

- Such states are particularly vulnerable due to weak governance, poor surveillance and the ineffective enforcement of laws.

- The next highest proportion occurs in the West Central Pacific Ocean, with 34 percent of the total catch being from IUU fishing.5

- 33 percent of the total catch in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, specifically the West Bering Sea is from IUU fishing.6

- In portions of the Pacific, a high volume of fish of 5 million tonnes is caught annually. The Arafura Sea which lies between Australia and Indonesia, is another region with high rates of IUU fishing.7

- In particular, Indonesia experiences losses of US 4$ billion a year in profits from IUU fishing.

- Between 2000 and 2013, many Indonesian vessels carried out trawling operations in the Australian EEZ without prior permission. This may have been caused by a reduction in fish stock within the Indonesian EEZ because of overexploitation and overfishing.8,9

2.2 Trends in Coastal State and Flag State Responsibilities

- According to the 2021 IUU fishing index, the top 10 worst performing countries in terms of coastal state responsibilities are Cambodia, Somalia, Vietnam, Myanmar and Taiwan, Kiribati, Timor Leste, Philippines, Seychelles and Yemen, indicating that the worst performers tend to be located across Asia and Africa.

- A noticeable trend is that the worst performers in terms of coastal state responsibilities tend to be located across Asia, Africa and Oceania and tend to be developing island states.

- In terms of fulfilling flag state responsibilities, the top 10 worst performing countries are China, Taiwan, Panama, Russia, Spain, Japan, Liberia, South Korea, Libya and Indonesia.

3. Impacts of IUU fishing

3.1 Economic Costs

3.2 Environmental Costs

- IUU fishing can have dire consequences for the preservation of biodiversity as it hampers fisheries management and conservation. This is because IUU fishing can lead to an inaccurate assessment of fish stocks, allowing fish stocks to be fished beyond limits that are considered sustainable.

- As a result, some major impacts on biodiversity include the possibility of species extinction, poor ecosystem health, the disruption of marine food webs, as well as reduced climate resilience for both fish stocks and fishing communities.13

- Climate change is altering ocean ecology, which is bound to affect marine ecosystems, leading to a reduction in catches. Thus, fishing malpractices may exacerbate the impacts of climate change.

3.3 Social Costs

- Rampant IUU fishing can sometimes be a consequence of failed states, leading to open access fisheries. IUU fishing tends to occur in environments that give rise to gross human rights abuses, corruption, human trafficking, tax evasion, piracy, and drugs.14 ,15 However, this is contested in the literature as some argue that crimes such as forced labor are more likely to be associating with IUU fishing and crimes such as human trafficking are much less likely.16

- Overfishing and habitat destruction as a result of IUU fishing, may in the long term aggravate existing political tensions. This may lead to a military conflict in the race to procure diminishing resources.

4. Potential Responses to IUU fishing

4.1 Preventive Measures

- One way of preventing IUU fishing would be to increase the risk of detection and reduce the economic incentives for fishermen.

- A relatively successful initiative involves the issuance of formal warnings to regulate IUU fishing.

- For example, the EU regulates the entry of IUU fish in the market by issuing formal warnings such as a ‘yellow card’ to non-EU countries to improve their efforts in preventing IUU fishing.

- If a ‘red card’ is issued the country is banned from the EU market. This was the case for Sri Lanka, where Sri Lanka was issued a red card due to failing to address IUU.

4.2 New Tracking Technologies

- Another potential response would be to capitalize on new tracking technologies such as blockchain18.

- An immutable ledger, blockchain allows individual transactions to be recorded while eliminating the possibility of them being altered or deleted.

- This would allow for increased supply chain traceability in the seafood industry.

- The technological capabilities of the private sector could be mobilized to monitor and increase the transparency of transshipment19

- The monitoring of fishing vessels could be improved by making it a condition that a vessel must explain or display its track history in order for it to land its catch. If a vessel is unable to do so, then it will not be able to land its catch.

4.3 Partnerships and Capacity Building

- Encourage the proliferation of organizations such as Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship and the Marine Stewardship Council to increase the traceability of supply chains in the seafood industry.20 This would pressurize other market actors to increase the transparency of their supply chains.

- Engage in capacity building efforts to equip law enforcement officers with the skills to tackle the complexities that arise from IUU fishing.

- The Fish FORCE Academy in Africa is a program organized by CSIRO, Australia’s national science institution are some examples of capacity-building training programs21.

5. Sri Lanka and IUU Fishing

- Sri Lanka has been involved in cases of IUU fishing. In 2015, the European Council banned imports of fisheries products from Sri Lanka due to IUU fishing concerns.22

- Major concerns by the European Council were related to Sri Lanka’s failure to implement international law obligations, inadequate monitoring, and the absence of sanctions in the event of IUU.23

- The main form of IUU fishing for Sri Lanka was in the form of unreported fishing by Chinese vessels brought down in 2013.

- A brewing source of conflict for Sri Lanka and India have been allegations of IUU fishing, specifically, illegal fishing carried out by Indian trawlers. Recently, on the 19th of December 2021, 8 Indian fishing vessels and 55 Indian fishermen were arrested by the navy for poaching in Sri Lankan territory.23This has been a persistent problem for Sri Lanka where Indian fishermen use bottom trawlers and trespass in Sri Lankan waters.

- The use of bottom trawlers cause severe scraping and ploughing of the sea bed with extensive loss of critical habitats such as seagrass beds and coral reefs, bycatch generation and loss of income to the local fishermen from Jaffna, Kilinocchi and Mannar Districts.24

- The Sri Lankan government’s initial response from 2013 to 2018 was to seize trawlers and arrest as many Indian fishermen as possible. This led to a humanitarian problem of hundreds of fishermen from India languishing in Sri Lankan jails.

- The Fisheries Act No. 59 of 1979 (Foreign Fisheries boats Regulation Act was amended to dictate that instead of arresting the fisherman, their boats would be taken away and only released upon the payment of a large fine.

- This change in legislation has been successful in reducing the amount of illegal fishing taking place on Sri Lankan waters.

6. Key Readings

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2001. International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing.

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2019. Regional Consultation on the Development of the Regional Plan of Action to Combat Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing.

Fuji, I, Okochi, Y, Kawamura, H. 2021. ‘Promoting Cooperation of Monitoring, Control and Surveillance of IUU Fishing in the Asia-Pacific.’, Sustainability.

Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. 2015, ‘Sri Lanka National Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing.’

Notes

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2001. International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal,

- Flag of State: The country under which a ship is registered.

- Cabral, R.B., Mayorga, J.2018. ‘Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing.’ Nat Ecol Evol 2, pp. 650-658. Accessed February 2022.

- Doumbouya, A, et al ( 2017), Assessing the Effectiveness of Monitoring Control and Surveillance of Illegal Fishing: The Case of West Africa.

- Cabral, R.B., Mayorga, J.2018. ‘Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing.’ Nat Ecol Evol 2, pp. 650-658. Accessed February 2022.

- Cabral, R.B., Mayorga, J.2018. ‘Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing.’ Nat Ecol Evol 2, pp. 650-658. Accessed February 2022.

- Cabral, R.B., Mayorga, J.2018. ‘Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing.’ Nat Ecol Evol 2, pp. 650-658. Accessed February 2022.

- Vince. J.,2007. ‘Policy Responses to IUU fishing in Northern Australian Waters’.Ocean Coast Manag, 50 , pp. 683-698. Accessed March 2022.

- Edyvane, K.S, Penny, S. 2017. ‘Trends in Derelict Fishing Nets and Fishing Activity in Northern Australia: Implications for Trans-boundary Fisheries Management in the Shared Arafura and Timor Seas.’ Fisheries Research, vol. 188, pp. 23-27. Accessed March 2022:

- Cabral, R.B., Mayorga, J.2018. ‘Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing.’ Nat Ecol Evol 2, pp. 650-658. Accessed February 2022.

- Sumaila, U.R, Zeller, D, Hood, L, Palomares, M.L.D, Li, Y & Pauly, D. 2020, ‘Illicit trade in marine fish catch and its effects on ecosystems and people worldwide.

- Tinch, R., I. Dickie, and B. Lanz. 2008. Costs of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing in EU Fisheries. London.

- Konar, M., Gray, E., Thuringer, L., and Sumaila, U. R. 2019. The Scale of Illicit Trade in Pacific Ocean Marine Resources (Working Paper). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Sumaila. U.R, Bawumia. M, ‘Fisheries, Ecosystem Justice and Piracy: A Case Study of Somalia’ Fisheries Research, vol. 157, pp. 154-163,

- Sumail, U.R, Jacquet.J, Witter, A.’When bad gets worse: corruption and fisheries’ EconPapers, Accessed February 2022:

- Mackay, M, Hardesty, B.D & Wilcox, C. 2020, ‘The Intersection between Illegal Fishing, Crimes at Sea and Social Well-Being.’ Frontiers in

- S. Widjaja, T. Long, H. Wirajuda, et al. 2019. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers. Washington, DC: World

- S. Widjaja, T. Long, H. Wirajuda, et al. 2019. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers. Washington, DC: World

- S. Widjaja, T. Long, H. Wirajuda, et al. 2019. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers. Washington, DC: World

- These are activities which involve the unloading of goods from one ship to another to reach its final destination.

- Daily Mirror. (2015). Illegal fisheries: red card for SL. [Online]. Available at: https://www.dailymirror.lk/53720/tech

- Daily Mirror. (2015). Illegal fisheries: red card for SL. [Online]. Available at: https://www.dailymirror.lk/53720/tech

- The Sunday Morning. (2021). Trouble Sea: illegal fishing in the territorial waters of Sri Lanka. [Online]. Available at: https://www.themorning.lk/trouble-at-sea-illegal-fishing-in-the-territorial-waters-of-sri-lanka/

- Karunaratne, R.K.A. 2020, ‘Unregulated and Illegal Fishing Boats in Sri Lankan Waters with special reference to bottom trawling in northern Sri Lanka: A critical analysis of the Sri lankan legislation.’

*Alisha Rajaratnam was a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. The opinions expressed in this Explainer, and any errors or omissions, are the author’s own.