COP26 Climate Summit and Sri Lanka’s Promise for Action

October 11, 2022 Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 min read

Image Credit – Markus Spiske/ Pexels

Toyesha Padukkage*

This LKI Explainer, ‘The Glasgow Climate Conference COP26 and Sri Lanka’ examines the importance of COP26 climate summit, global climate action leading to COP26 , key achievements and shortcomings of COP26, and what needs to be addressed at the next climate summit (COP27).

Contents

- What is COP26 and why is COP26 important?

- The path to COP26 and its goals

- What COP26 achieved

- Why COP26 fell short

- What’s Next?

- Sri Lanka’s Role at COP26

1. What is COP26 and why is COP26 important?

- The 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) generally known as the 26th climate summit of the United Nations (UN) was held from 31st October 2021 to 13th November 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland after much anticipation from the one year postponement of the climate conference due to the COVID19 pandemic outbreak in 2020.

- Article 7 of the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change1 1992 to which 196 countries and the European Union are signatories, implemented the Conference of the Parties (COP) as a decision-making body for reviewing and monitoring the implementation of the UNFCCC. The COP continues to be a significant platform to parties to the convention as well as to intergovernmental organisations and non-governmental organisations with observer status, the UN organisations and its agencies, for making collective decisions about the next global climate agenda.

- The United Kingdom (UK) hosted the COP26 annual two-week conference in 2021 under the presidency of Alok Sharma, a UK member of parliament, and there were representatives from 194 countries, 120 Heads of states and governments, and a total of 38,000 accredited delegates attending COP26.

- COP26 is considered as the “most important COP since Paris”2 as it included the first progress evaluation of the 2015 Paris Agreement which instigated national commitment and measures to limit the rise of global temperature to below 1.5°C – 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

2. The path to COP26 and its goals

- Since the adoption of Kyoto Protocol3 in 1997 and the 2015 Paris Agreement,2 the COP also serves as a platform for meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) and for meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA) which are the decision-making bodies of the climate agreements respectively.

- The significance of the Kyoto Protocol is that it was established to reduce emission of six greenhouse gases and to hold the developed state parties accountable for their emission reduction targets under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities”. There are currently 192 state parties to the Kyoto protocol.

- The Paris Agreement is a significant achievement in the climate governance journey as it is a legally binding international treaty that was adopted by 196 state parties. The Paris Agreement allowed state parties to determine their own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)5 for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and for adapting to climate change.

- As the state parties are required to renew and strengthen their NDCs targets every five years under the Paris Agreement, COP26 marked the start of a new five year cycle for climate actions with ambitious pledges of NDCs.6

- The state parties to the Paris Agreement got together at COP26 with the primary goal of finalising the Paris rulebook (adopted in 2018) which sets key milestones and guidelines for implementation of the Paris Agreement. The Paris rulebook includes finding solutions for carbon markets, resolving transparency issues when adhering to national commitments and reaching an agreement inclusive of all governments to keep alive the goal of global temperature below 1.5°C.

- COP26 attendees also intended to continue the discussion on the progress of climate change and to understand the current climate trends and impacts. The latest IPCC Report: the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) provides an insight to the increasing climate trajectories and accordingly, the global temperature will exceed the 1.5°C and 2°C above pre-industrial levels during the 21st century unless stronger commitments and necessary actions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are taken in the coming decades.7

- The impacts of a 1.5°C – 2°C warmer world include more frequent and intense weather patterns, droughts, floods, storms, landslides and sea level rise. Global climate scientists assert that from 2020 to 2030 the global emissions must reduce at a rate of 7.6% per year to keep under 1.5°C global temperature rise and a 2.7% per year to stay below 2°C global temperature rise.8

- NASA points out that the global emission rate has dropped by 5.4% in 2020 due to Covid19 pandemic, but the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to grow at the same rate.9 Moreover, aside from the discussion of climate progress and impacts, one of the goals of COP26 was to address the importance of sustainable recovery from Covid19 in solidarity with vulnerable parties to tackle climate change.

3. What COP26 achieved

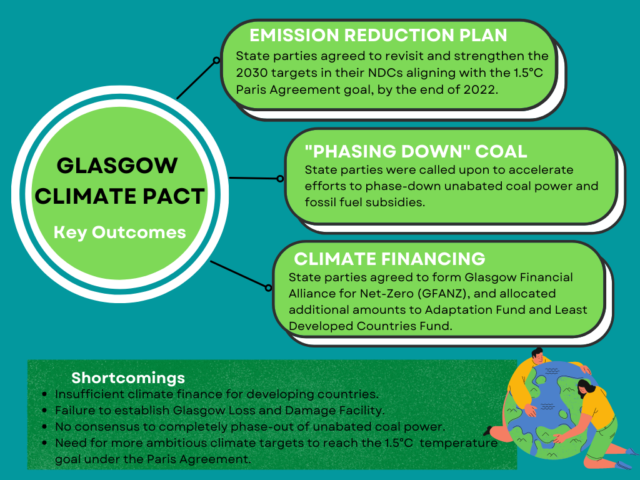

- The Glasgow Climate Pact agreed upon 10 at COP26, urged “phasing down” unabated coal with 65 countries committed to phase out coal with more than 20 new commitments, and 48 countries joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA) which is the world’s largest leading alliance on phasing out coal.

- COP26 ensured the key role of the private sector (including financial leaders, businesses, companies, banks and investors) through the formation of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ)11 to halve current global greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 with the target of keeping the global temperature below 1.5°C within reach. The GFANZ is a commitment of 450 top financial enterprises to decarbonise the global economy.

- The Global Methane pledge launched 12 at COP26 signified the devotion of more than 100 countries to reduce global methane emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030 and the pledge covers 46% of emissions. Through the Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forests and Land,141 countries pledged to end deforestation in 91% of the world forest cover by 2030. Brazil pledged to cut down emissions by 50% and to put an end to illegal deforestation by 2030.13

- State parties to the COP made new financial pledges for the Global Adaptation Fund (over USD 350 million) and the Least Developed Countries Fund (over USD 600 million) with the goal of helping vulnerable populations to build resilience. Under Article 6 of the Paris Rulebook, the Global Adaptation Fund will also receive 5% of the “share of proceeds” through cooperative and market-based carbon trading systems.14

- COP26 launched a work programme on mitigation ambition and implementation will be followed by an annual high-level Ministerial meeting on pre-2030 ambition. In the context of adaptation, countries agreed to establish a 2 year Glasgow-Sharm el Sheikh Work Programme on the Global Goal on Adaptation (The GlaSS) for addressing vulnerability and resilience against impacts of climate change. COP26 also launched Adaptation Research Alliance (ARA).

- COP26 recommended new rules for voluntary cooperation, international carbon crediting mechanism and non-market mechanism under Article 6 of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The key elements of the Glasgow Climate Pact include goals of phasing-down of unabated coal power, reducing emissions, halting and reversing deforestation, and speeding up the shift to renewable energy.

- The United Nations identifies outcomes of COP26 as a compromise and yet, COP26 ensured “near-global net zero” NDCs from 153 countries.15 It can be considered as a significant achievement of COP26, to have agreed upon the Glasgow Climate Pact and to have finalised the outstanding elements of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

4. Why COP26 fell short

- Parties to the COP26 were initially called upon to “phase out unabated coal power”, but after several rounds of negotiations, parties agreed to “phase down unabated coal power”. It can be observed that despite the historic call in the Glasgow Climate Pact for a “phase out” coal power, a few coal-reliant countries have indicated that they will not completely discontinue using coal until the 2040s or later.

- Although the Climate Finance Delivery Plan assured the goal of mobilising USD 100 billion each year as climate finance, the low-middle income countries lacked climate financing especially for adaptation and for other adequate climate actions. According to UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report 2020,developing countries need USD 70 billion per year to cover adaptation costs, but the Adaptation Fund received only an addition of USD 356 million at COP26 and the Least Developed Countries Fund was only allocated an amount just over USD 600 million to help build resilience in vulnerable populations.16

- State parties established the dialogue on loss and damage finance, however, the most developed countries resisted the G77 and China’s initiative to establish a Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility. Nevertheless, the state parties to COP26 agreed to a working plan for the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage and the dialogue on loss and damage will continue in the next climate summit.17

- The small island states, climate activists and experts are still concerned whether the emission reduction targets, commitments, funding and climate actions agreed upon at COP26 are ambitious enough to reach the target of keeping global temperature well below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Mia Mottley, 18 the Prime Minister of Barbados during her speech at COP26, mentions three shortcomings in the global climate agenda: i)) the world will lead in a pathway to 2.7°C without more mitigation, climate pledges and NDCs, and even with more, it is still likely to reach 2°C, ii) the climate actions/ commitments are based on technologies which are yet to be developed, and iii) finance commitments for climate actions and climate adaptation are not being executed as promised.

5. What’s Next?

- The next session of the Conference of the Parties (COP27) will take place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt from 7th to 18th November 2022. The host country, Egypt, is extremely vulnerable to climate change as it is densely populated and according to the Egypt country analysis by the UNDP,19 climate impacts are most likely to be felt in agriculture, aqua-culture and fisheries, coastal zones, human habitat and settlements and water resources. Moreover, it is expected that by bringing the COP27 to Egypt, the focus will not only be on Egypt but on Africa too as Egypt is situated in the North East corner of the African continent and Africa is the most vulnerable continent to climate change.

- COP27 is expected to advance climate actions made at COP26, to discuss the climate risks and progress of climate mitigation and adaptation, and to review the commitments under Glasgow Climate Pact. The primary focus of COP27 will be on climate finance. COP27 will also continue the dialogue on loss and damage, and will further climate practices and solutions adequate for the risks and danger posed by climate change.

6. Sri Lanka’s Role at COP26

- Impacts of climate change are experienced by all sectors of a country and affect the livelihoods of people. According to the National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change Impacts,20 Sri Lanka is vulnerable to climate impacts such as global warming, sea level rise, sudden weather patterns including heavy rains, prolonged droughts, and flash floods.

- At the COP26 summit, Sri Lanka made a commitment to achieve carbon neutrality target by 2050 and agreed to fulfil the following NDCs by 2030 including: i) shifting contribution of renewable energy sources by 70% (from electricity generation), ii) increasing natural forest cover by 30%, and also iii) reducing carbon emissions by 14.5%.

- Sri Lanka is striving to achieve climate commitments through several measures. Sri Lanka has led the Colombo Declaration for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in 201921 which aims to halve the Nitrogen waste by 2030, and now calls upon other nations to tackle the global nitrogen challenge. Sri Lanka also co-leads the “Global Energy Compact for No New Coal Power” 22 and intends to work together with the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA)to phase out the usage of unabated coal and to tip the scales of consigning coals to history.23

- The special presidential task force for the creation of a “Green Sri Lanka with sustainable Solutions for Climate Change” works together with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to address matters relating to financial resources, technological transmission and environmental sustainability.

- Sri Lanka needs to mobilise climate finance set up by the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement 24 in order to implement the necessary adaptation and mitigation tasks, and to negotiate bilateral agreements for low-carbon economic development. The Green Climate Fund as a part of the National Adaptation Plan will also provide financial assistance to implement adaptation mechanisms.25 Further, Sri Lanka welcomes the involvement of Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS) and the Commonwealth Litter Programme (CLiP) along with the UK Government marine experts to tackle issues related to X-Press Pearl pollution case. Sri Lanka is determined to develop a ‘Green Sri Lanka’ advancing current climate commitments with the support of and increased collaboration with developed countries.

Notes

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992). https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf

- UN Climate Change Conference UK (2021).COP26 Explained. [online] Available at: https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/COP26-Explained.pdf [Accessed 27 Dec 2021]

- United Nations Climate Change (2021) What is Kyoto Protocol? [online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol [Accessed 2 Jan 2022]

- United Nations Climate Change (2015). The Paris Agreement 2015. [online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf [Accessed 27 Dec 2021]

- United Nations – Climate Action (2021) All about the NDCs. [online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/all-about-ndcs [Accessed 2 Jan 2022]

- Ibid.

- Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (2021). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report – Headline Statements from the Summary for Policymakers. [online] Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Headline_Statements.pdf [Accessed 24 Dec 2021]

- United Nations (2021). Climate Action Fast Facts. [online] Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/fastfacts_temperature_rise.pdf [Accessed 29 Dec 2021]

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology (2021). Emission reductions from pandemic had unexpected effects on atmosphere. [online] Available at: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/emission-reductions-from-pandemic-had-unexpected-effects-on-atmosphere https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/COP26-Explained.pdf [Accessed 27 Dec 2021]

- United Nations Climate Change (2021). Glasgow Climate Pact. [online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2021_L16_adv.pdf [Accessed 1 Jan 2022]

- Bloomberg (2021). The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero. [online] Available at: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/63/2021/11/GFANZ-Progress-Report.pdf [Accessed 2 Jan 2022]

- European Commission (2021). Launch by United States, the European Union, and Partners of the Global Methane Pledge to keep 1.5C Within Reach. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_21_5766 [Accessed 24 Dec 2021]

- UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021 (2021). Glasgow Leaders Declaration on Forests and Land Use. [online] Available at: https://ukcop26.org/glasgow-leaders-declaration-on-forests-and-land-use/ [Accessed 2 Jan 2022]

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (2021). The Paris Agreement’s New Article 6 Rules. [online] Available at: https://www.iisd.org/articles/paris-agreement-article-6-rules [Accessed 30 Sept 2022]

- United Nations (2021). COP26: Together for our planet. [online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop26 [Accessed 7 Jan 2022]

- United Nations Environment Programme (2021). Adaptation Gap Report 2020. [online] Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2020 [Accessed 5 Jan 2022]

- United Nations Climate Change (2022). About the Santiago Network. [online] Available at: https://unfccc.int/santiago-network/about [Accessed 27 Dec 2021]

- UN Climate Change (2021). Speech: Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados at the Opening of the COP26 World Leaders Summit. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PN6THYZ4ngM [Accessed 03 Jan 2022]

- United Nations Development Programme – Climate Change Adaptation (2022). Egypt. [online] Available at: https://www.adaptation-undp.org/explore/northern-africa/egypt#:~:text=Egypt%27s%20large%20population%20makes%20the,to%20analyze%20possible%20adaptation%20measures [Accessed 25 Dec 2021]

- United Nations Framework for Climate Change (2016). National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change Impacts in Sri Lanka 2016 – 2025. [online] Available at: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NAPC/Documents%20NAP/National%20Reports/National%20Adaptation%20Plan%20of%20Sri%20Lanka.pdf [Accessed 03 Jan 2022]

- United Nations Environment Programme (2019). Colombo Declaration calls for tackling global nitrogen challenge. [online] Available at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/colombo-declaration-calls-tackling-global-nitrogen-challenge [Accessed 01 Jan 2022]

- Presidential Secretariat (2021). Sri Lanka proud to be a co-lead of “Global Energy Compact for No New Coal Power”. [online] Available at: https://www.presidentsoffice.gov.lk/index.php/2021/11/02/sri-lanka-proud-to-be-a-co-lead-of-global-energy-compact-for-no-new-coal-power/ [Accessed 25 Dec 2021]

- Powering Past Coal Alliance (2021). New PPCA members tip the scales towards ‘consigning coal to history’ at COP26. [online] Available at: https://www.poweringpastcoal.org/news/press-release/new-ppca-members-tip-the-scales-towards-consigning-coal-to-history-at-cop26 [Accessed 23 Dec 2021]

- Climate Change Secretariat Sri Lanka (2021). Updated Nationally Determined Contributions Under the Paris Agreement ON Climate Change Sri Lanka. [online] Available at: http://www.climatechange.lk/CCS2021/NDC%202021%20-%20English.pdf [Accessed 25 Dec 2021]

- Green Climate Fund (2022). Sri Lanka. [online] Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/countries/sri-lanka [Accessed 23 Dec 2021]

*Toyesha Padukkage is a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. The opinions expressed in this Explainer, and any errors or omissions, are the author’s own.